The fast-moving nature of biotechnology innovation means architects and designers for Regeneron have to plan for researchers’ requirements to change by the time new laboratories open on the Tarrytown, N.Y., campus. The campus is undergoing a $1.8 billion expansion, adding 900,000 sf of new laboratory and office space, along with additional parking, amenities, and infrastructure to support research and development. The new laboratories will be able to evolve as the biotech industry finds new ways to use artificial intelligence, CRISPR genome editing technology, robotics, and other advances. The company is developing indoor and outdoor spaces enveloping those labs to foster collaboration among drug discovery scientists, all while providing amenities to support the campus’s fast-paced culture.

Benjamin K. Suzuki, Regeneron’s executive director of engineering, design, and construction, says his team has had to adjust its plans to accommodate both science and technology advances as well as Regeneron’s growth, including the acquisitions of other biotech assets.

“Accounting for flexibility/adaptability in the planning process—allowing us to pivot our current programs to satisfy new scientific directions—is critical in how we design and plan our facility,” says Suzuki.

Regeneron has developed 13 medicines approved in the U.S. and/or other countries since its founding in 1988, including receiving emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 for a medicine to treat people exposed to COVID-19. The company posted $3.9 billion in net income on revenue of $13.1 billion in 2023. It employs over 13,400 employees worldwide and reported investing $4.4 billion in research and development in 2023.

The campus expansion exemplifies the company’s strategic growth and need for more space for more scientists and scientific modalities, says Suzuki.

“As part of the $1.8 billion investment, we’re going to create 1,000 new jobs at our Tarrytown site. As a five-year major project, there will be a tremendous benefit to the local and surrounding market and workforce with the addition of 1,300 or more construction workers on site at peak,” says Suzuki.

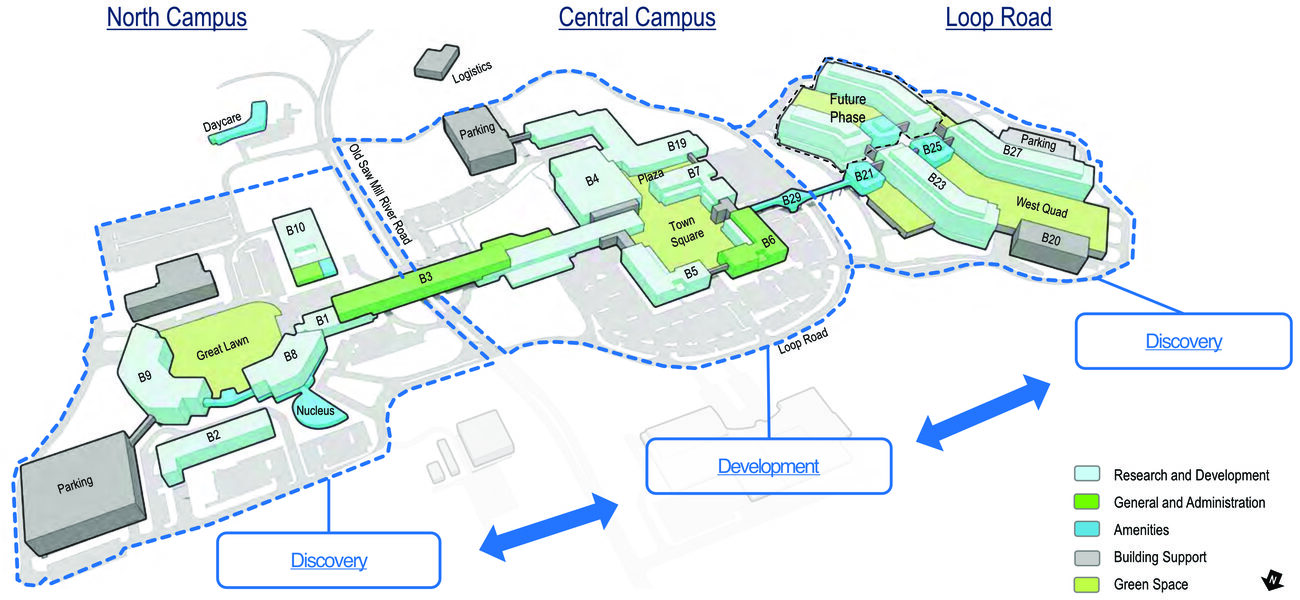

The expansion includes two phases: Loop Road West, now under construction, and Loop Road East, a future phase. The design features of Loop Road West telegraph Regeneron’s vision to create spaces—indoor and outdoor—that foster collaboration among scientists, through the position of workspaces in relation to each other, the design of laboratories configured for maximum flexibility, placement of functions based on their shared affinities, and accompanying amenities including green spaces to enhance the employee experience.

Rethinking Space Use to Emphasize Collaboration

The expansion provides Regeneron the opportunity to update its thinking on how to organize its space, says Suzuki. When the new Loop Road buildings open, the Tarrytown campus will operate in three geographic centers that are physically connected: a development cluster in the middle bookended by two discovery clusters.

Central to this thinking is how the various research departments function, their affinities and common support/resource needs that can be shared, as well as the movement of scientists from one area to another—and encountering spaces where they can meet easily. “As we think about where to put things and existing amenities—what we should expand and what we should augment—what is very important to us is balancing efficiency and connectivity. As we contemplated the nature of these important spatial and programmatic components in how they connect, the level of transparency, access to daylight, circulation and energy, a theme throughout the design is the celebration of science with visual connections to the labs, robotics, and sandbox areas with exposed infrastructure,” says Suzuki.

The expanded campus will include miles of hallways, walkways, and pedestrian bridges. Setting the development cluster in the middle, between two groups of buildings devoted to drug discovery, will help minimize the time scientists have to travel between meetings.

“The goal is to create space that bridges discovery with development. In discovery, scientists focus on identifying potential therapeutics, while in preclinical development, we test for safety. By designing a lab that centralizes these functions, we can enhance collaboration between teams, streamline workflows, and ensure a seamless transition from early-stage research to clinical results, ultimately speeding up the path to bringing new medicines to patients,” explains Suzuki.

Elements of the design that convey this thinking include:

The Preclinical Manufacturing and Process Development Building (PMPD)—The PMPD building represents the centerpiece of Regeneron’s campus-as-collaboration design. It has six football fields worth of process space, including space for trains of bioreactors ranging from 40 liters to 500 liters. The interior glass walls reflect research leaders’ desire for light-filled spaces that celebrate science, says Suzuki.

“The PMPD building is process driven and resembles a glass manufacturing plant, with a big, long, straight run,” says Suzuki, noting that the linear concept becomes a Z-shape because of constraints posed by adjacent wetlands on the site.

Other features of the PMPD building include a 22-foot-tall high bay with a catwalk spanning the structure’s length to support servicing mechanical units, blower fans, and other equipment without occupying lab space (and eliminating the need for ladders); and a tailor-made setting for town hall-type meetings in front of an impressive backdrop of scientific equipment such as large stainless steel vessels and the network of infrastructure serving them.

Loop Road Bridge—The 500-foot-long Loop Road pedestrian bridge connecting the central campus and the new campus provides both a pedestrian pathway between development and discovery zones and spaces where employees can hold small meetings and get coffee.

The bridge features tinted electrochromic glass that reduces glare and eliminates infrared light, which is a risk for laboratory materials. “The key thing for us is that we don’t have brand-new buildings with blinds going up and down. You can see through it,” says Suzuki.

Collaboration hot spots embedded between various functional areas—The Loop Road expansion includes meeting spaces nestled among R&D areas and amenities.

“When you talk to our leaders, they tell us that most of the innovation—the eureka moment—isn’t always at a lab bench or at someone’s desk. It is often when collaborating in a conference room,” says Suzuki. “They’re processing all of the stuff in the lab areas. They’re analyzing all the data in the office areas, and they cross in between, but then they get together and these brilliant minds put it all together.”

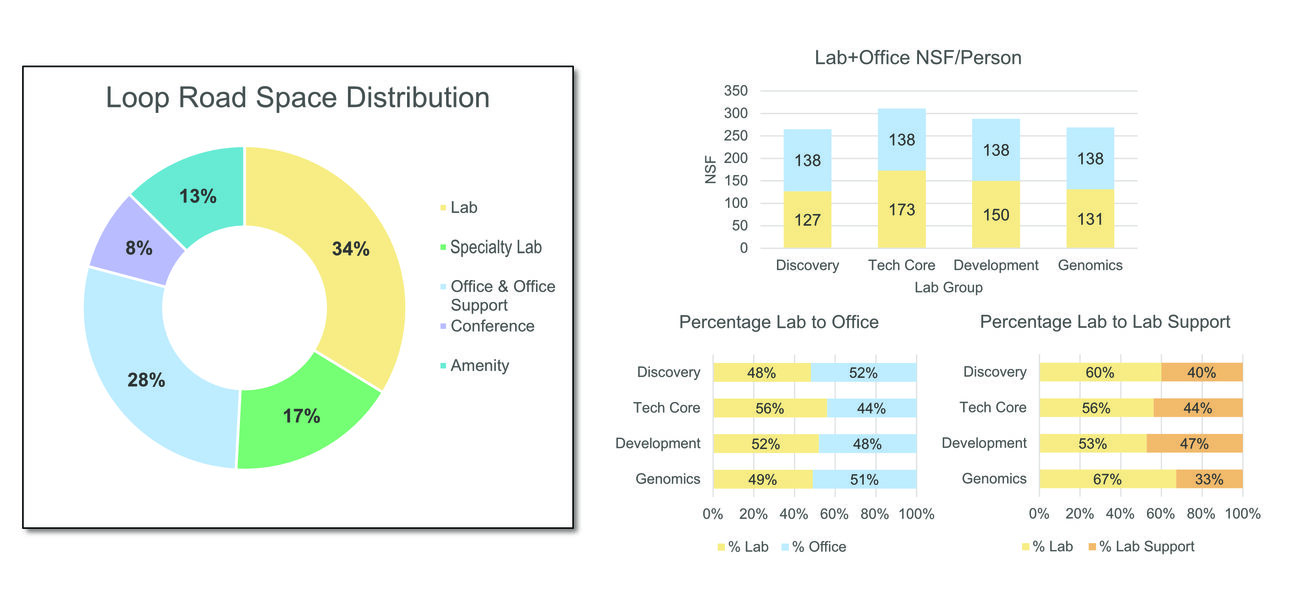

Designing Laboratories Using a “Per Process” Metric

Regeneron’s new laboratory layouts enable scientists to install the latest equipment and technology. Instead of calculating space requirements based on the number of scientists, the design accounts for the space required by scientific processes—that is, the technology, robotics, and other equipment required to discover new molecules.

“We are evolving from a per-person metric to a per-process metric,” says Suzuki. “Not how many scientists, not how many linear feet of benches, not how many drawers and cubbies, but what processes can I get done?”

Two drivers in particular led to this change, says Suzuki. One is the rise of robotics, computing, and artificial intelligence, which means designers need to cater to more dry research that is automated. The second is a trend of convergence among different medical research areas—such as overlapping genomics research with aging or cardiology or hearing or vision— that, when combined, actually take up less space in the lab while integrating multiple lines of inquiry.

“When you think of the lab of the future, we’re really talking about a room full of machines and automation,” says Suzuki. “It’s about the scientific process that’s happening, impacting the space needs more so than individual scientist themselves.”

Suzuki says his team produces modular design prototypes with multiple configurations of equipment and space for future flexible layouts. They show both virtual mockups and some physical models to scientists as part of a consensus-building process.

Even though the company tailors its technology systems to its specific needs, the design team is pursuing a modular approach, building 30 different lab configurations from a kit of 25 parts. Some of the equipment fits into overhead service carriers that allow for flexible arrangements. The laboratory designs include fixed utilities, mobile casework, and equipment for Regeneron engineers and robotic specialists to fit into their laboratory benches.

Working with a set number of configurations enables Regeneron to manage costs, says Suzuki. Picking one lab design would be too limiting, and allowing infinite configurations would be too costly.

As for power, Regeneron prioritizes environmental sustainability and is working to generate new renewable electricity in its local communities and beyond to support the transition to a low-carbon future. It generates 0.5 megawatts of solar power at its Tarrytown campus and is developing an additional 3 megawatts of solar power for its enlarged campus. The company is also installing Tier 4-level emergency generators for a backup power supply. Its goal is to match 50% of its electricity consumption with electricity from certified renewable energy sources by 2025 and match 100% of electricity consumption with electricity from certified renewable energy sources by 2035.

Amenities Spur Scientists’ Work—and Play

Regeneron’s campus expansion also accounts for employees’ personal needs and the company’s active lifestyle, high-tech culture. These features include:

- A main street-style corridor running through the Loop Road expansion, including pop-up shops and food carts like an ice cream truck, as well as spaces where employees can learn about cooking. Retail spaces will host a dry cleaner, a company store, concession stands, and food venues.

- Specialized programs including an athletic center and a daycare.

- Green space to accommodate the company’s “outdoor culture.” Regeneron’s clubs and employee resource groups include soccer, pickleball, running and bicycle clubs, as well as music groups. “The outdoor environment was very important to our employee population, so we’re trying to create outdoor spaces with amenities,” says Suzuki.

- Bright colors that provide accents as well as signs featuring Regeneron branding messages and patient testimonials.

Controlling a “Major Campus Expansion Project”

To Suzuki and his team, the size of Regeneron’s campus expansion may be viewed as a large-scale major project—analogous to a major highway or public transit project in the public sector that is synonymous with ballooning budgets and delayed timelines, according to a well-known paper on the Iron Law of Mega Projects by Bent Flyvbjerg. Avoiding that kind of spectacle was a priority that drove cost and time-sensitive critical thinking and decision-making throughout the planning, says Suzuki.

Indeed, as is common with large-scale projects, the designs had to undergo and adapt to major changes—to be “reprogrammed”—more than once. Factors driving change include new technology and modalities, as well as growth in new scientific areas and the impact in acquisitions of other biotech assets.

“Science moves very quickly and sometimes unpredictably, and we have to reprogram sometimes to accommodate the scientific directions we choose. Science and research priorities drive innovation and growth. And as our science adapts to many fast-paced technologies merging in the research fields of scientific medicine, we have to adapt our program accordingly,” says Suzuki.

By Michael S. Goldberg