Like many large organizations, Toronto’s University Health Network had space reduction on its wish list in the 2010s. But with four hospitals, a space utilization rate of between 80% and 100%, and 6 million sf of space divided up among 30,000 staff, physicians, and students, it was never entirely clear how this could be achieved. Then came COVID, and suddenly UHN planners realized that with smart planning and a little technology, they had an opportunity to cut the office space needs of some teams by 30-40% and make many employees happier at the same time.

Rx for WFH (Work from Home)

Pre-pandemic, cutting down lease costs seemed almost impossible says Ian McDermott, executive director, redevelopment and chief planning officer for UHN. “We were thinking, how the heck do we do this?”

When the pandemic hit, they found that technology made it possible for many people to work from home effectively and happily. “Then as pandemic restrictions were easing and people were permitted to come back to work, a lot of staff said, ‘Wait a minute, I love the flexibility of working remotely,’” says McDermott.

This created a double opportunity for the network. UHN could enhance employee satisfaction and cut its leased office space costs. But there was a catch: The shift would require undertaking a massive and complex change management program. For the largest research health network in Canada—a sprawling system that includes a major medical school (The Michener Institute of Education), and seven different research institutions—making hybrid employment sustainable required a number of changes in design and policy.

First, McDermott and his team set up a process to identify who could work from home, as most healthcare is necessarily hands on.

Next, McDermott and his team created a template for a written agreement between hybrid workers and their managers that defined the conditions under which those workers would be allowed to work remotely.

Hybrid workers were also issued new gear. Digital networking tools were not a problem, as most teams were already on Microsoft Teams. But every hybrid worker needed to be issued a laptop, a monitor, a wireless keyboard, a mouse, and a cell phone.

Another important investment was to give all the hybrid workers lockers in which to store their personal belongings. “It is theirs. It is only theirs,” says McDermott. “They can store their material in there, they can leave their personal items in there so that they can grab those personal items and go to a workspace.”

Workstations for hybrid workers were designed to be as similar as possible to discourage workers from jockeying over particular spaces. “We tried to standardize the size of our workstation, so it isn’t like people can’t pick their favorite workstation, or nobody wants to pick the one that is small or old,” says McDermott.

At the same time, many paper files were digitized, freeing up space and making remote access to information easier.

The planning team also needed to analyze what UHN’s spatial needs would be going forward. Of the 6 million sf occupied by the network, 1 million sf was office space, and about 200,000 sf of that tranche was used by people who could be hybrid workers.

As they looked at how space would be used going forward, planners realized that to gain any cost savings, they would need to reconfigure some of the floorplans, dividing floor space between dedicated workstations and flexible workspaces.

Not all of this work was done using computer design tools. McDermott says that while managers always want to make space configuration decisions remotely, he insists on a site walk. “There is nothing like going and doing a site walk to figure out what you need to do in terms of developing a space,” he says.

Changes also needed to be made further up the ladder. For example, the planning team decided that only managers who directed people would get an assigned office, and they had to commit to working in the office at least three days a week. “If they thought they were only going to be in one or two days a week, they did not get an office. End of story,” he says.

The team also installed thermal occupancy sensors, as a way to assess how the space was actually being used.

Managerial Changes

Other changes were more managerial. For example, team managers had to decide which days their crew would be working in the office. “One of the things that I said to the leaders of each group was that you can’t all choose Tuesday and mandate that you all have your teams here on Tuesday, so we do need you to cooperate—what a crazy idea!—cooperate to say which days,” says McDermott.

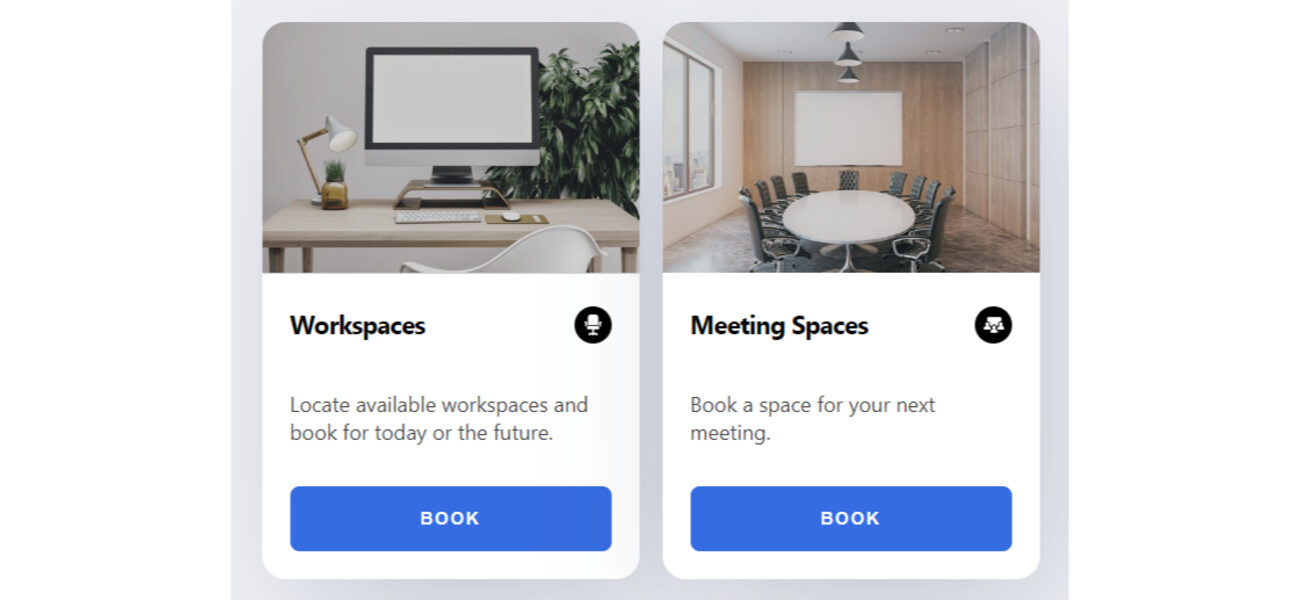

They also needed a system to enable people to reserve workspaces and meeting rooms, something UHN had not had before. “It’s hard to believe, but in an organization that had four hospitals and a college and seven research institutes, to book a meeting room, you had to send an email to one person,” he says. “It was crazy.”

The system also had to offer more than a simple ability to reserve a space. “We needed an online system that everybody could go to and find out what is in the meeting room; not only about the size and capacity, but what technology is in there,” he recalls.

Workers were also given limited power to reserve spaces on the system, as a way to prevent attachment to particular spots. “You can only book it for one day. You can’t book the same spot every Monday from now until the end of the year,” he says.

So far, the new reservation system seems to be working well. “People are happy, they can come in, they can grab their coffee, they can socialize with people, and there is never a worry about booking space,” says McDermott.

McDermott says that UHN went into this conversion process with some special organizational advantages. The biggest was that for about six years now, facilities have been managed by a single office, the Facilities Management Planning Redevelopment & Operations (FM-PRO) team.

“What that did, of course, was give us the opportunity to be consistent across the board,” he says.

The fact that UHN already had a long-term strategic plan in place also helped planners to focus on the opportunity. That plan called for 50% growth, mostly in beds, as well as a steep cut in the 1.1 million sf of space leased by the health network.

The plan was crucial, says McDermott. “That then really helped us drive a space policy. It is very, very critical, because if your organization doesn’t actually have a space allocation policy, it becomes nearly impossible to implement anything. If you don’t have a policy that you can turn to all your staff with and say, ‘This is the policy, this is how we’re doing it,’ they are going to say, ‘Well, why? Why do I have to do it?’”

Needless to say, he adds, that plan needs executive support and support across the organization.

Beyond adding convenience for workers, there have been unexpected operational advantages as well. The hybrid work reconfiguration, for example, made it possible to bring the FM-PRO team together in a purpose-built space in one building, something the group did not have before.

The Transition Continues

Today, the transition to more flexible workspace continues. Right now, the planning team is looking into whether some of the laboratory space could also be organized through a centralized reservation system.

Another challenge ahead is to convince some of the physicians that they don’t necessarily need an office, which has always been an important status marker for doctors. “Physicians are no different than academics: Space is sacred to them, and while they may never set foot in their office, they cannot give up their office. That is a hurdle; wish me luck on trying to figure out how to get them to start sharing and using bookable, hybrid space!” says McDermott.

But while these and other challenges remain, McDermott is sure UHN has made the right bet with hybrid work. “I heard different people say, prior to 12 months ago, that it was all going to disappear,” he says. “It’s never going to disappear—I’m sorry. We just have to figure out how to do it.”

By Bennett Voyles