With 20% of clinical faculty supporting research studies and 12,000 studies under way at any given time, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is a highly collaborative organization at the forefront of both research and clinical care. Supporting collaboration and innovation is a primary focus of its facilities management strategy, and Mayo Clinic’s “condo” model, a central paradigm of its translational research workplace, has proven indispensable in the institution’s mission to deliver world-class research and clinical care. Now, a recent initiative is harnessing data in new ways to build upon and expand the power of the condo to advance Mayo Clinic’s mission for decades to come.

The Condo

At Mayo Clinic, a condo is a group of investigators with a well-defined mission who elect to share research space and equipment to foster collaboration and innovation in translational research. An investigator group can create a condo by approaching Mayo Clinic’s research space and equipment subcommittee, which is charged with creating the spaces that will accommodate these collaborations. By forming a condo to share space, staff, tissue culture rooms, and equipment, investigators can more efficiently deliver the research that translates to clinical care.

Mayo Clinic created the condo model to make the most of existing space. “But, as people saw the synergies and the benefits of the condo, it grew,” says Linda Sanders, research operations administrator for Mayo Clinic’s enterprise-wide subcommittee on research space and equipment. “In addition to the collaborative benefit, the investigators in a condo may also be able to share more equipment, space, and staff. We’re up to about 13 condos right now, and there isn’t much turnover. Our oldest—the gastrointestinal condo—has been around about 10 years, and it has continued to grow every year.”

To monitor how well the condos are working, the subcommittee annually surveys all staff in each condo anonymously; they assess grants and funding; and they tour the condos, scoring and ranking them and compiling the results into a dashboard.

Condo User Feedback

Surveys reveal that satisfaction with Mayo Clinic’s condo spaces is high, says Greg Ramseth, a project manager for HDR, Mayo Clinic’s master planning consultant. “Although the portfolio of buildings on the Rochester campus is pretty broad in terms of age, strong satisfaction is reported across spaces, which I think speaks to Mayo Clinic’s legacy of being able to adapt space to new uses.”

“Very, very seldom do we hear, ‘My space is perfect, thank you so much,’ but we did actually hear that this year,” says Sanders. “So we feel like we’re making progress and trending in the right direction. To see that in quantifiable data is very rewarding, to know that they’re satisfied with what we’re doing.”

“The only factor rated as less satisfying is the amount of space,” adds Ramseth, “which I take simply as a confirmation that we’re getting responses from researchers, because researchers always want more space.”

To augment the survey data, Ramseth and Sanders have also conducted focus groups, asking users more general questions: Outside of the laboratory, what is most important for the future of research? In your opinion, what promotes and inhibits collaboration? Are there research environments in which you’ve worked that you think are particularly effective or innovative?

“Physical proximity was something that was stressed a lot,” says Ramseth. “Corollary to that is access to clinicians; that is absolutely required for effective translational research. That mixture of laboratory and clinical spaces has a long-lasting impact of producing very high-quality research.”

Users have expressed a dual desire for both more social space and more hybrid work options, which, Ramseth notes, isn’t as contradictory as it might seem. “We’re hearing that a mixture of social and hybrid work spaces is actually very valuable. For instance, when a relationship begins face to face, especially a relationship between a researcher and a clinician, it’s then much easier to continue in the virtual space.

“One challenge is that when there’s a large group together in the room, in person, they get that casual time together when the meeting is over, but the people who were attending virtually are cut off from that,” he says. “Attacking that problem is the next frontier.”

“Mayo Clinic has a strong and growing focus on AI and digital strategies,” says Sanders. “That is paramount to the type of space that we’re building in our new facilities or in our existing facilities. But that collaborative area is also very important to the clinicians and the investigators as they move forward.”

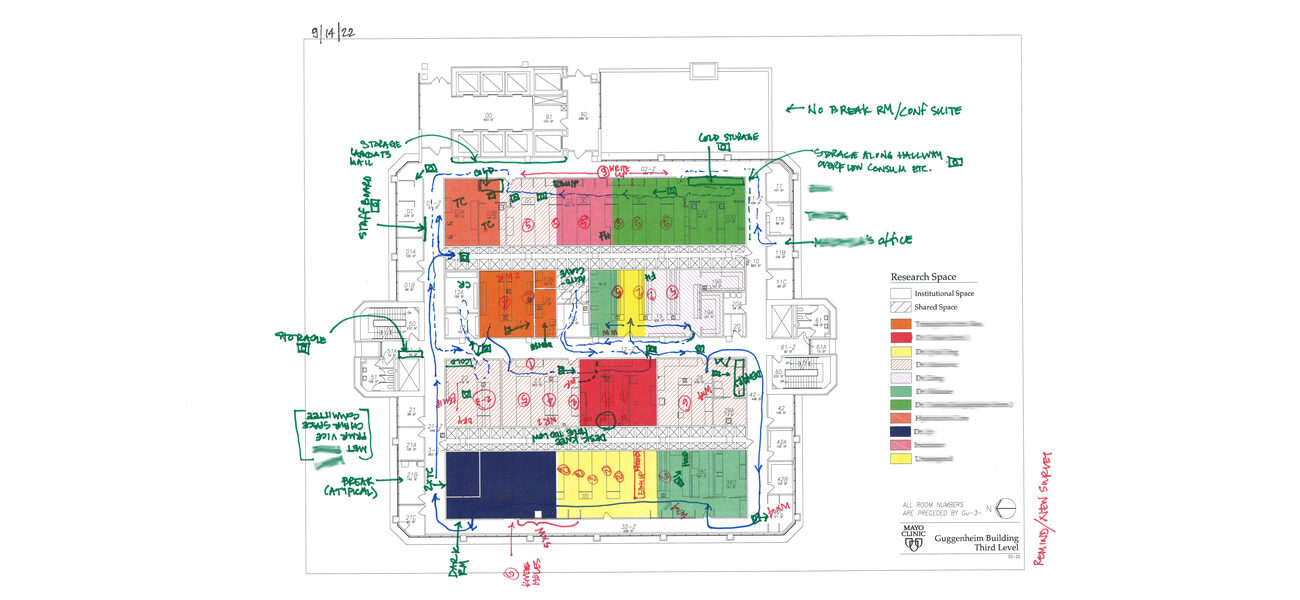

Condo Space Tours

In the most recent laboratory space tour, Ramseth and Sanders walked through about a million square feet of research space, carrying along a large whiteboard clipboard that tracks every space that they pass through, to make sure they don’t miss any. “We’re as guilty as every other institution in not recognizing how much space we actually have and how it’s actually being utilized,” says Sanders. “So it’s a very beneficial activity to tour every space.”

One thing they did on this tour is compare the condos’ space usage with the space-planning model developed for Mayo Clinic’s newest facility for basic and translational research—the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Building—which opened in December 2023. “In each space,” says Ramseth, “we asked ourselves, ‘Is anything happening here that couldn’t happen in this more open, collaborative model of the research environment?’ We found that about 95% of those research activities could indeed occur in a space like Kellen.” They also closely observed the utilization of bench areas in the condos. They found that tissue culture space was well utilized, an observation that was congruent with survey data.

The “Living Master Plan”

A powerful planning tool called the “living master plan,” co-developed by Mayo Clinic and HDR, brings together the information gleaned from surveys, focus groups, and space tours with data from a variety of other sources, including facility management software, NIH grant data, and the U.S. Department of Energy’s PuRe Data (Public Reusable Research Data) on co-authorship of research papers.

“What you can do with this analytically is pretty interesting,” says Ramseth. “It’s not deterministic—it’s not like you just press a button and it tells you what to do—but it lets you look at things in a different way pretty rapidly.

“For instance, if you look at the spatial representation of the PuRe Data, the co-authorship of papers, you can get a sense of the collaborators’ proximity,” he says. “And when you look more closely at that, you start seeing things that make you want to dig deeper. If, for example, you notice that there’s a group that’s working well together despite being distributed across the campus, you might then want to look into why that’s the case. You can ask, is this something that you would assign an affinity value to, if you were going to relocate people?

“You can also look at grant funding against square footage, which gives you a sort of ‘heat map’ to understand how productive some of these spaces are, and then compare that with a more traditional method of analysis, such as the square footage per full-time employee.

“When you present this sort of thing to the steering committee, it sparks a lot of new ideas and questions for further analysis,” says Ramseth. “And because we’re building this from scratch, we can add in all of those analytical tools.”

They are now developing a tool that will analyze the relationship between productivity per square foot and density of staff. “The preliminary results coming out of that are very interesting,” says Ramseth.

“This living master plan is going to help me better understand who can fit, and where they fit, and where that research is being conducted, so that when we need to make changes, we can do it with a better understanding of all of the inputs that we’re using to make those decisions,” says Sanders. “This data-rich tool is going to adjust our workflow and our ability to conduct our space analysis and assessment in a much better way.”

Visualizing the Future of Mayo Clinic’s Research Workplace

The living master plan includes a “capacity and needs dashboard” that brings together myriad growth information metrics to aid future planning. Users can tweak variables—such as current and desired utilization, annual growth of existing programs, annual growth from recruitment, future space additions, and hybrid work factors—to visualize the impact of such changes over time.

“This dashboard is key to us in our space planning, because we recruit a significant number of clinicians every year who are engaged in research,” says Sanders. “Although their primary function is to see patients, these individuals also work with other colleagues and other investigators, and so they may need a footprint in some laboratory. They don’t need an entire laboratory, like a pure scientist would, but we do need to accommodate them and provide them with equipment and shared facilities.”

Factoring the increased number of clinicians into their research space and their research growth will help them more accurately identify what renovations may be needed or when it’s time to request a new building.

Next steps may include real-time utilization monitoring. “It could be infrared, or phone tracking, or badges,” says Ramseth. “We just think that there’s at least some value in trying to figure out whether as-reported and as-observed actually match up with reality.”

By Deborah Kreuze