After a 2017 fire sped up the timeline for construction of a new science building, University of Delaware faculty and staff needed to make hard choices about how the building should be organized and what features and facilities it should include. Politically, the easiest path would have been to divide the space by department, but Peter Krawchyk, the university’s vice president of facilities and university architect, had a different idea of how to make the decision, one he argued would work better: “We didn’t begin with any kind of programming—number of principal investigators, fume hood counts, or anything like that. We began with ideas and culture.”

Making the Model

A veteran campus planner, Krawchyk likes to begin every project by developing a mental model that sums up the institution’s goals for the building. “The goal isn’t meeting the budget. The goal isn’t a net-to-gross ratio. The true goal is, what is the purpose of what we are doing together? Purpose with a capital P,” he says.

The idea of the mental model came to him through a combination of experiences—first, the course work for a doctorate in literature, and then his experience as an architect and a campus planner. In the same way every detail in a good novel grows out of a core theme, it was helpful if they could begin with a single vision for the building.

Rather than focus on simple metrics, such as how big the offices are, a mental model keeps planners focused on the larger aims. “I’ve learned that if I can create some kind of story about the project and the goals, it’s very helpful. It keeps people focused. When it’s nine months later and you’re going through the details, you need people to understand why other details fit the bigger picture.”

Creating a truly shared vision depends on a series of conversations with three or four people, and not necessarily the architects, advises Krawchyk. “My frustration with architects and professionals generally is that they all speak jargon, and the clients don’t understand the jargon. The most successful architects I’ve worked with are the ones who are able to get the information and then translate their questions in a way that the people they’re talking to can understand.”

If, as in this case, one of the goals is to create an interdisciplinary space, a model can also be useful for getting people to think beyond the needs of their own department. “It’s not like you’re taking something away from them. You’re actually trying to add things for everybody. So you have shifted the conversation by having that model in people’s minds,” he says.

Krawchyk, a former race car driver, said something people who race cars like to say is also pertinent to mental model conversations: “‘You have to learn to be comfortable being uncomfortable.’ If your project is under control, you’re not pushing the envelope. Everybody in the room needs to push their ideas for the project to come up with a model. That’s everyone in the room. It’s not just university people. It’s not just the architects. It is everyone.”

Such discussions may include design questions, says Krawchyk, even with scientists. “I think they’re very receptive normally. The difficulty is they’re usually coming from very outdated facilities. You have to break them out of the mold of, ‘Yeah, but my office is so cramped, I can’t find all my books.’ You have to explain to them how much better the new building will be. You may have to tour other facilities, but if you put the work in, they’ll come on board,” said Krawchyk.

“It’s especially important to include as broad a range in faculty contribution as possible. Be sure not to overlook younger faculty—they are often more vested in the project’s success, because they will be occupants for a longer period of time,” says Krawchyk.

In the end, “you need something like an elevator pitch,” he says. “You need to be able to walk in and say, ‘This is what this building is; this is how it’s going to perform.’”

“You take that model and you filter all your decisions through it. You make sure that every decision is enhancing or leveraging that model,” he says.

X Marks the Spot

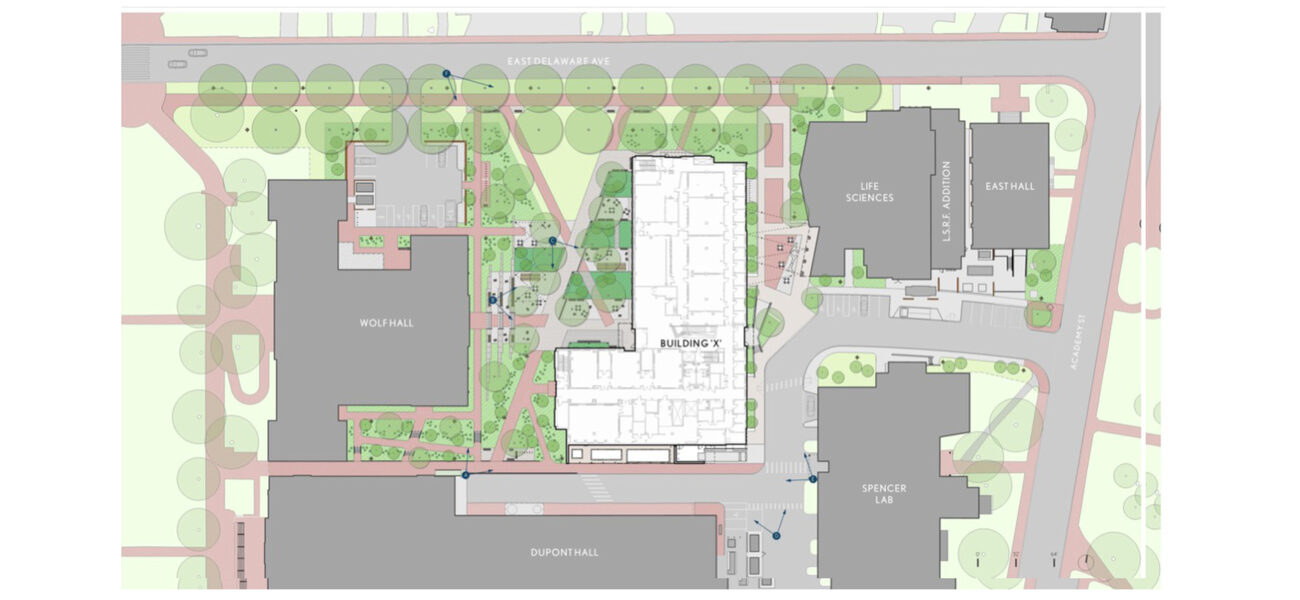

In the case of the $120 million Building X, as Krawchyk dubbed it, when the faculty and administration discussed what they wanted the new building to accomplish, they realized they needed a space that could be used by a variety of science departments, all at the same time.

“This wasn’t going to become a biology building. It wasn’t even going to become the life sciences building. We wanted something different and that led to the title of Building X, because you don’t know what’s in the building, and that opened up possibilities for thinking about what this project could become,” says Krawchyk.

As John Pelesko, former dean of the College of Arts & Sciences put it, “Calling it ‘Building X’ makes it clear that this was a blank slate. This was an opportunity to imagine what a modern science laboratory building could be and how it could be organized.”

Instead of making assignments by department, planners decided to divide the departments between experimentalists and theorists. Theorists would be relocated to other parts of the campus, while the experimentalists would be given the cutting-edge laboratory space they need. “We wanted to make sure that this building advanced the research enterprise,” says Krawchyk.

To further encourage cross-disciplinary discussions, each floor would have a theme associated with it, as well as instruments that would encourage movement. Biologists, for instance, would have to go down to the quantum physics floor to get to the microscopy imaging suite. “We don’t think of it as interdisciplinary. We think of it as more of a collaborative collision of creativity: ‘Let’s put these things together. Let’s see what happens,’” recalls Krawchyk.

He also believes the model encourages faculty to share equipment with people outside their own department. “I think it was easy for faculty to see the university does not have the financial resources to buy new equipment for everyone,” says Krawchyk.

To promote more interaction and further inspire collaboration, planners added a café and set the building entrances in such a way as to encourage people to pass through Building X as they cross the campus.

The building they eventually designed will have 131,000 gsf (67,000 nsf) with space for 230 benches and 50 principal investigators—twice the number as in the laboratory building it replaces. Core facilities include imaging, fabrication, characterization, flow cytometry, biophysics, and a vivarium, with the dominant research focus on mind-brain, quantum, and human diseases. Undergraduate teaching and common space each get 5,400 nsf.

Supporting Players

Beyond spending time working out how the space in the future building should be used, Krawchyk favors finding architects who are comfortable collaborating and sharing their ideas, even when they are still taking shape.

“I want to see the sketches you threw in the trashcan. I don’t want to see the polished rendering that was printed out of the computer 20 minutes before I got here, with people and birds and trees…I want to see things early on, when decisions can be made. Most architects think the client wants to see, ‘Look how professional we are.’ Similarly, advises Krawchyk, campus planners shouldn’t interview just the polished principals during the architect selection process, but the junior staff who will be doing most of the work. “What are they like? Are they people we think we can work with?”

Even when all that work is done, Krawchyk warns that planners should expect plenty of delays and reversals. “Tell me how you’re going to make decisions if you have a business where you can never fire any employee and you are completely responsible for a large group of 18- to 21-year-olds—and they live in your business!

“In a corporation, one person can make a decision,” says Krawchyk. “The CEO says, ‘This is what we’re doing,’ and that’s it. No discussion. It’s never that way in an institution. You just have to expect you will need time for the decision to percolate.”

By Bennett Voyles