A 2018 change in leadership at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), accompanied by indicators of significant growth, set the stage for redefining how the nation’s largest science and energy laboratory views and manages its 4-million-plus-gsf space portfolio. In the shift from a landlord-tenant cost-recovery model managed by outside partners to a restructured internal space management organization, ORNL launched a wide-ranging initiative to improve utilization of existing space and increase transparency. Among the measures implemented were: creating a space authority in each of the lab’s eight research directorates; convening an annual space summit; walking down the entire space at least twice every year; and building an integrated workplace management system based on extensive data gathering.

Leading 3,500-plus world-class research scientists and engineers across the different research directorates to a shared vision of space as a strategic asset and valuable resource for the entire organization—as opposed to the property of any individual principal investigator (PI)—was a “cultural journey,” according to James Serafin, director of ORNL’s Laboratory Modernization Division.

“We believe that space management is as much about people management as it is about the facilities capabilities,” says Serafin, noting that facilities staff in an institution the size of ORNL do not have the scientific expertise to adjudicate space conflicts.

“How can we challenge a research PI on why one-third of their lab space is being used for equipment that hasn’t been touched in over 10 years?” he continues. “There can be a lot of tension around these issues, but we’ve learned that if you simplify and find a basic level of information, you can successfully organize people around a cultural shift in how they view space. Effective space management involves effectively setting expectations.”

From Abundance to Space Shortage

Managed by the University of Tennessee-Battelle, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, the 80-year-old ORNL operates with a staff of roughly 6,500 and hosts 3,200 guest researchers a year. Its annual research budget is roughly $2.5 billion. The average age of the 208 buildings on its 4,421-acre campus is about 41 years.

Before the space realignment, the lab’s 4.4 million sf were managed by the UT-Battelle organization. That contract had instituted a landlord-tenant relationship that followed a cost-recovery model charging the various directorates and business lines for space according to square footage and designation—lab, office, or storage. The agreement accorded significant latitude to the various divisions when making decisions about space usage, allowing what Serafin describes as “some poor behaviors” to develop. For instance, instead of acquiring more office or storage space when needed, a research group could simply convert an unused lab to the new function, avoiding any budgetary impact.

With plenty of space available, this free-market system enabled the groups to control their own destiny for many years, without significant centralized scrutiny. However, the anticipated boost in funding created an increased demand for space, tilting the supply balance to the point that a half-dozen old buildings previously slated for demolition were instead reoccupied. A change in management approach was clearly needed.

Restructuring and Communicating

Tackling the challenges of ORNL’s diverse research portfolio and complicated organizational structure, the space planning group first looked inward. An early change was separating the tactical space management functions from the strategic, putting day-to-day operations in the hands of the tactical team while the strategic planning group focuses on long-term future needs.

“This separation allows us to stay forward-looking and move from a reactive to a more proactive method of space planning and management,” says Sandra Moats, who, in her role as facility planning engineer supporting the strategic space planning efforts, helps shape and scope ORNL’s capital improvement program and works with the directorates to prioritize where funds should flow.

The initiative also created pathways to communicate with the directorates about their space needs. Each directorate now appoints a space authority, a role typically filled by its chief operating officer (COO), to validate space needs. The divisions underneath also designate a space representative, one per division, to monitor those needs.

“This is important,” says Moats. “It lets the directorates manage nuanced issues like space allocation, seniority, and who gets that window office. We established a single point of contact—one person with whom we can build a relationship—for each directorate. To increase transparency, we meet with each directorate space authority individually every month, and we have a meeting with all of them every quarter.”

Space Summits and New Facility

Another productive communication vehicle is the annual space summit. The event grew out of a meeting in 2021 with all the directorate COOs and ORNL operations leadership to explore the space implications of the staff return to campus post-pandemic. Getting all those leaders together in the same room for a focused discussion about their office space needs was not only successful in developing a path forward, but also pointed the way for planning future office space projects.

The growth forecasts prepared by the COOs early the following year indicated that lab space should be the focus of the 2022 summit. A new translational science facility slated for completion in 2024 would free up roughly 25,000 sf in existing buildings. The new facility will house a variety of programs—advanced scientific computing, basic energy sciences, materials science, fusion energy sciences, high energy physics, and basic and applied research—providing labs with noise isolation, electromagnetic shielding, and low vibration. Along with labs, it will have high bays, roughly 100 offices, collaboration and conference spaces, and amenities.

However, its approximately 90,000 sf and the space it will leave vacant will not be sufficient to fill the demands of the multiple directorates, and the space planning staff felt unable to prioritize the competing needs themselves.

“We can evaluate things like availability and utilization, but with multiple strategies and multiple compelling arguments, we need help and direction from our leadership,” says Moats.

The solution was to make the second summit like a Shark Tank for lab space.

After cataloging all the space coming available, the facilities group enlisted an advisory panel of six leadership representatives from operations, research, strategic planning, and business to listen to pitches from all the directorate COOs as they justified their lab space needs.

“The advisory panel is key,” continues Moats. “It helps us prioritize the lab space requests, balancing things like science alignment, funding, and ORNL’s initiatives and goals. With that input, we were able to assign the laboratory space that will be opening up. Having these decisions made at the beginning of our fiscal year allows us to hit the ground running with things like lab renovations using that year’s money.”

Engaging the directorate COOs in the decision-making is also important, Moats points out. “Having them present their needs in front of lab leadership elevates the process and increases its transparency. It also adds an element of social pressure and supports the cultural shift to see space as a strategic asset and a valuable resource.”

Remedying a Dearth of Data

Upgrading the space database, originally a series of static spreadsheets compiled in the 1990s, was another pivotal piece of the realignment initiative. ORNL selected FM:Systems for its new integrated workplace management system (IWMS) and began compiling previously lacking space data through interviews and walk-downs.

In the course of conversations with researchers, the facilities team realized that their space vocabulary was markedly inconsistent. Space was being defined based on the equipment in the room or the function it was performing, not the room’s physical dimensions and capabilities.

“We needed a way to talk about the space that cross-cuts all of our directorates, with the facility attributes dictating the space types,” says Moats. “Take everything out of the room. What do you have?”

Now, space is described as belonging, first, to one of three main categories: lab, office, or storage. Labs are sorted into seven types of attributes: chem–bio, high bay, general, specialized, large equipment, research, shop, and support. The office and storage headings each have three subcategories: hard wall, cubicles, and open workstations for the former; and general, laboratory, and hazardous for the latter.

Poor space utilization was an issue that surfaced during the extensive walk-downs. For example, one high bay space was housing office cubicles, while a chem-bio lab was being used for storage. Seeking to capture this utilization data in the IWMS, Moats and her team established two metrics to track: highest potential use and stewardship.

“Larger spaces like high bays are more valuable and scarcer than, say, storage,” she explains. “The idea behind highest potential use is to match the demand of the research with the potential of the space.”

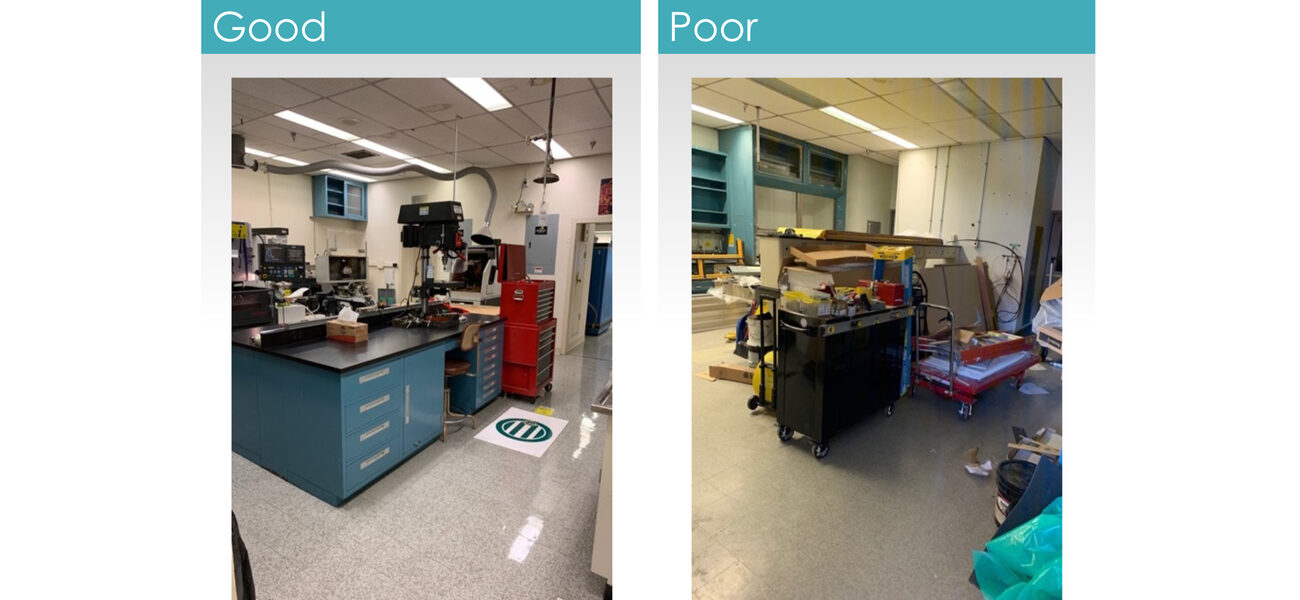

The rating system for office stewardship is a simple, easy-to-understand scheme of good, fair, or poor, according to ORNL standards for paint, furniture, and carpet. The lab grading system, which requires more than just a visual check, is still a work in progress.

For improved transparency, this data is given to all directorate COOs on a regular basis.

“Tracking and sharing lets them know what good looks like,” says Moats. “It also lets them know that we are watching and adds an element of social pressure.”

Walk-Downs Improve Utilization

Observations gleaned from the walk-downs help validate office space occupancy. Input into the IWMS, this information allows the ORNL team to monitor vacancies and turn them into hoteling space that can be reserved through the workplace system. It has been very useful for tracking utilization rates, according to Serafin.

To keep current, a dedicated staff member conducts regular walks-downs, with the goal of touching every space at least twice a year.

“If our space data specialist needs help with performing walk-downs, he can get it from someone in space planning,” says Serafin. “If someone on the management or planning team needs to walk down a space for another reason, for example, checking on the condition of a particular high-bay lab, they will feed that information back to that individual.”

Shared with the COOs and directorate space authorities, the feedback has been instructive.

“It can be enlightening to see through this lens,” he notes. “Since we started tracking and sharing space stewardship, we’ve seen a 13 percent improvement in our lab space stewardship.

“It’s amazing how powerful data is when you are trying to change a perspective,” continues Serafin. “It has brought transparency to our space process, and now people understand that space doesn’t belong to a group division or directorate. It belongs to Oak Ridge, and the decisions we make are based on what is best for the lab.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl