What the university needs: A spacious, modern science building, with an additional 5,000 sf. What the university has: An old, dark, rather cramped classroom building, built for a different era in education, with inadequate systems, and no room to expand. It’s a common problem on university campuses, and in many cases solving it requires flexibility, creativity, and patience. At the University of Pittsburgh, Howard Skoke, AIA, of EwingCole Architects and Engineers and the university’s own Ilona Beresford worked together on a six-month master plan to devise a $65 million modernization. The project, scheduled to begin construction in May 2019, will open the building to new uses and adapt its systems for health and efficiency. At the same time, it will preserve a historic exterior and cost far less than a new building.

No Room to Swing

Crawford Hall is part of a four-building block devoted to the university’s science programs. With six stories, two below ground, it houses the neuroscience and biological science departments. Both programs have been growing fast, so space is at a premium.

Built in 1969, the building needs modernizing badly, but the process has to be carefully planned, in part because of the lack of swing space that could allow the project team to work on larger blocks of the building. “There is just no available space, especially when it comes to lab swing space,” explains Beresford, project manager for the University of Pittsburgh. “We have to engage in phased construction strategies.” For instance, the renovation of a large lecture hall has to be performed in the summer, because there is no other place to put classes of 130 students.

As with many lab projects, the Crawford Hall modernization will focus on creating shared spaces to accommodate changing grant funding and research needs while maximizing available room. “Shared graduate carrel space, workspace, shared microscopy, shared tissue culture—what could we do to share, share, share?” says Beresford.

“There was a priority to make the individual labs into more generic flexible labs and widely increase the number, increasing the amount of lab space proportional to the floor,” says Skoke. The building’s lab spaces were constructed during an earlier era and were filled with small rooms rather than the “ballroom” spaces preferred in today’s scientific institutions.

The biological science spaces are more expansive than the neuroscience ones, because the neuroscience researchers had concerns about ergonomics, acoustics, and pathways, preferring to be able to get to their own labs without walking through someone else’s. Still, says Beresford, the two departments are highly motivated and enthusiastic about gaining some much-needed improvements. “The user groups were both great to work with. They have massive space deficiencies and were ready and armed with the data we needed.”

As part of the modernization, the building’s vivarium—a fish and rodent facility in the lower basement that is currently underused—will be upgraded to ABSL-2 status and expanded to provide more capacity, better support spaces, and a dedicated elevator.

Moving Mechanicals Upstairs

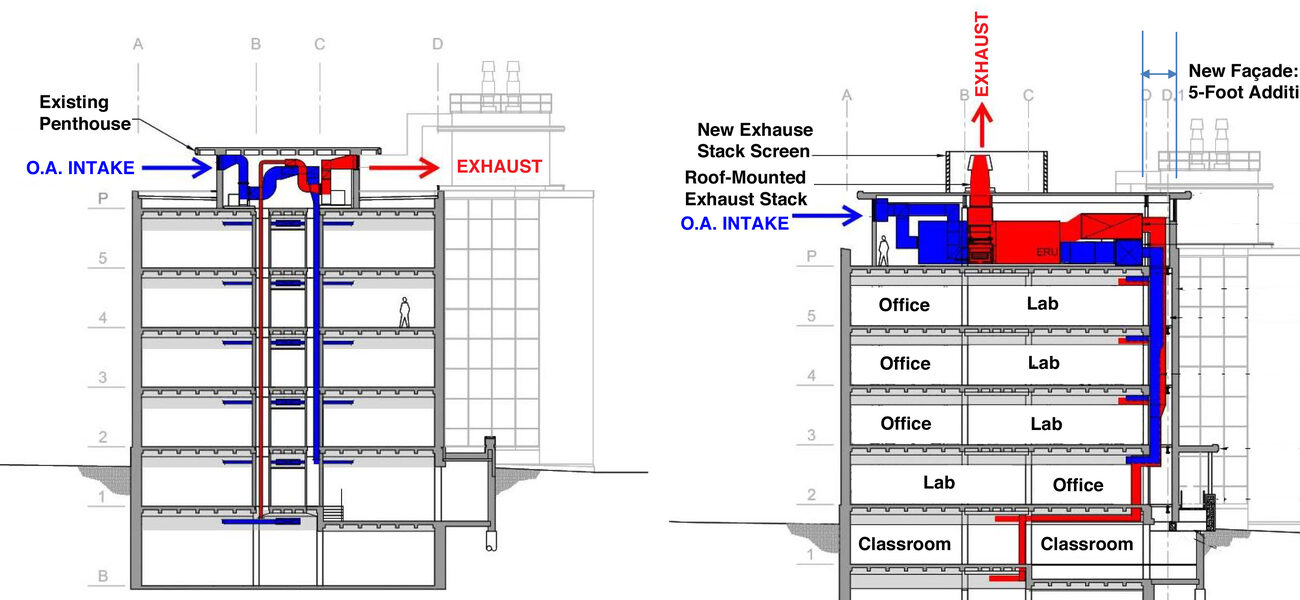

Along the way, the team sought to upgrade the building’s systems for greater energy efficiency, to the point of being able to seek LEED Silver certification. Because of the lack of available space inside the building, the solution ended up being to double the size of a penthouse on the roof that governs much of the building’s mechanical systems.

They also plan to build out about 5 feet on the south side of the building—the only side they can touch because of requirements to preserve the public-facing façade—to provide room for new ductwork, which brings the building up to current standards for allowable fan horsepower, single-pass air in laboratory spaces, and improved air change rates in other areas. This allows the team to move airshafts and mechanical systems out of central areas and create more open spaces for labs, classrooms, and support services. The change will nearly double the exterior-wall-to-corridor measurement, from 22.5 feet to more than 40 feet.

Another issue in Crawford Hall is the inadequate 12-foot floor-to-floor height. The concrete grid construction means the building has many large columns that block the sightlines important to today’s lab and teaching spaces. Working within the restrictions of that floor height was one of many constraints facing the study team. Moving mechanical systems to the penthouse will free up space currently being used for mechanical rooms, while columns that serve as airshafts can be eliminated as their functionality is moved to the newly expanded south side.

The penthouse will contain the air intake and Strobic fan exhaust, along with air handling and energy recovery units. At the same time, it will maintain connectivity to the rest of the four-building science complex.

The EwingCole plan focused the redesign on moving private offices to the north side of the floor plate, allowing for larger labs with more regular and flexible bench spacing. The original late-’60s windows are single-pane, and one priority was to introduce more natural light while improving energy efficiency. On the south façade, the project will increase the glazing to introduce more natural light into the labs.

Historic Façade

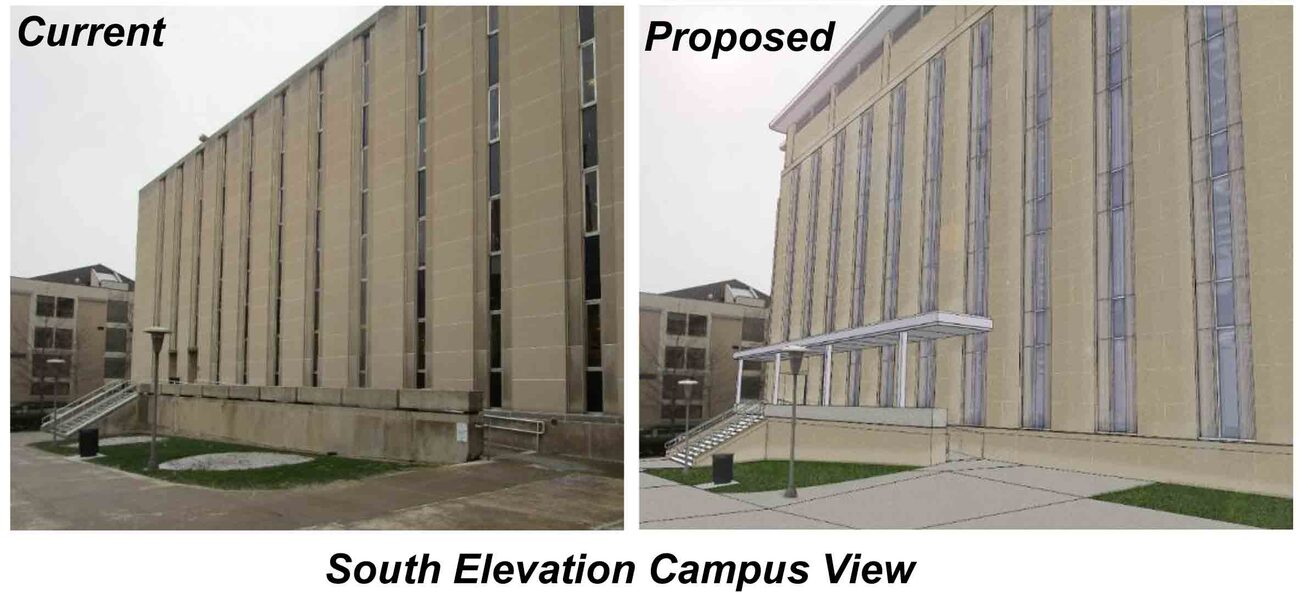

Crawford Hall is located at the edge of the university campus, and is visible from the adjacent Schenley Farms residential neighborhood. The local historic district expressed concerns about any renovation of Crawford Hall, citing its historical value as an example of the late international style of architecture.

To address the neighbors’ concerns, EwingCole’s preliminary design alters nothing on the north and west sides of the building—the sides that are most visible from beyond the campus—besides replacing the windows with more energy-efficient ones. The east side will see only the slight modification of some large louvers.

As part of working with the neighborhood to create an acceptable renovation plan, the team held two town hall meetings for local residents, and the Schenley Farms neighborhood groups joined the university in support of the plan when it went before the Pittsburgh Historic Review Commission. Over the course of three hearings, the university and EwingCole persuaded commissioners to agree to changes to the façade, including the larger penthouse (which will be made to appear similar to the building below) and the alterations to the south side. On that side, designers came up with a plan to enlarge the window area while keeping the same proportions of the original design. Historical commission members were dubious, but agreed to the plan after the team brought in a model to show how the new glazing—which adds vertical strips of fritted (translucent) glass to either side of the windowpanes—will be harmonious with the existing building design.

“That was a major win for us, because there was no way the University of Pittsburgh was going to invest $65 million on renovating this building without improving the quality of natural light in the new, more open labs,” explains Skoke.

‘Another 30 Years’

Another improvement is the addition of much-needed student gathering spaces suitable for group work or informal meetings. The central student area on the ground floor repurposes an underused entrance, requiring renovations for accessibility and protection from the weather.

The transformation will take place over two academic years and three summers, and the summers are key to completing it on time. “We’ll vacate two stories at a time,” says Beresford, who hired a construction manager as a consultant on the feasibility study, a practice she recommends for similar renovation projects. “Definitely involve the CM early on in the process just to get the best pricing and phasing options. Then again, that ties in with milestone cost estimates, each stage of the way. Then a viable phasing strategy which, again, is very important on our campus.” To add another wrinkle to the scheduling challenge, researchers and administrators strongly preferred to move as few times as possible, because each move might mean a gap of months in investigative time. “Especially these people on tenure track, it can ruin their chance of tenure,” she explains.

Beresford says the master plan was very well received in her user groups. “They weren’t inflating their program needs,” adds Skoke. “They have a great science program, and it’s growing. Due to their success, they can’t meet demand.” He estimates that modernizing Crawford Hall will give the building at least another 30 years of useful life.

By Patricia Washburn