Lease arrangements for office and laboratory space have historically been mostly for smaller companies, but are now becoming increasingly popular as a way for large research institutions to find an entrée into or expand in congested and expensive urban centers quickly, cost-effectively, and with more flexibility than building new. But leasing comes with its own set of considerations that potential tenants must navigate, including understanding the usable size of the area that they are renting, their access to building infrastructure, and responsibility for operating and maintaining shared mechanical systems.

“Just like designing a lab for a pharmaceutical company is very different than designing a lab building for an academic research institution, working with a developer on a new building or a tenant on an interior fit-up in a multitenant building is a specialty unto itself,” says Chris Leary, architect and principal of Jacobs KlingStubbins in Cambridge, Mass. “Tenants are wise to become informed consumers.”

Leasing has long been popular with smaller companies who can’t afford to build new facilities, but now large pharmaceutical companies and academic medical institutions are finding value in the model as well, says Leary.

Leasing may not only prove more cost effective than new construction, it also enables institutions to more quickly become established in popular research clusters around Boston, San Francisco, and New York, says Leary. Such densely populated centers usually have a shortage of available space, and it can take years to obtain the necessary permits to build biomedical facilities.

Leased spaces also can be negotiated for short periods, giving institutions more flexibility in the rapidly evolving research environment.

“Often, we’re seeing in large urban areas that institutions have to develop a building which makes economic sense—a size of 500,000 sf or more—and most people don’t need or want that,” says Leary. “You can’t logically or economically build a facility of that scale on your own.

“The delivery model of people building their own buildings is becoming rarer and rarer in those markets,” he says.

Advantages of Leasing

There are four main advantages to leasing: Schedule, access to competitive core markets, financial flexibility, and real estate flexibility.

Research institutions want to locate in core competitive markets to enable collaborative research and partnering with others in these clusters, says Bill Kane, vice president at BioMed Realty Trust in Cambridge.

“Those core markets have a high barrier to entry and sometimes take a long, patient investment outlook to enter into them. The tenants, on the other hand, are under time constraints,” says Kane.

“If you want to build 500,000 sf in Boston, that plan has to be in your head six to nine years ahead of time,” adds Leary. “Whereas in a lease environment, if somebody else has already developed, or begun to develop the building, move-in can be much quicker. We see large companies deciding on very short schedules to come to Boston.”

Even businesses that can afford to build new facilities are trying to utilize their capital more efficiently, notes Kane. There can be a financial advantage to leasing, as opposed to having facilities costs and operating risks on the books.

Real estate flexibility manifests in two ways: The ability to more easily and less expensively pick up and move as research centers migrate to new areas across the United States; and the buildings themselves can be easily changed/adapted.

“The good thing about a lease is it could be written for as short as two to 10 years, so when the world changes, companies can move on,” says Leary.

Leased facilities are more flexible internally because developers must accommodate different needs to attract tenants.

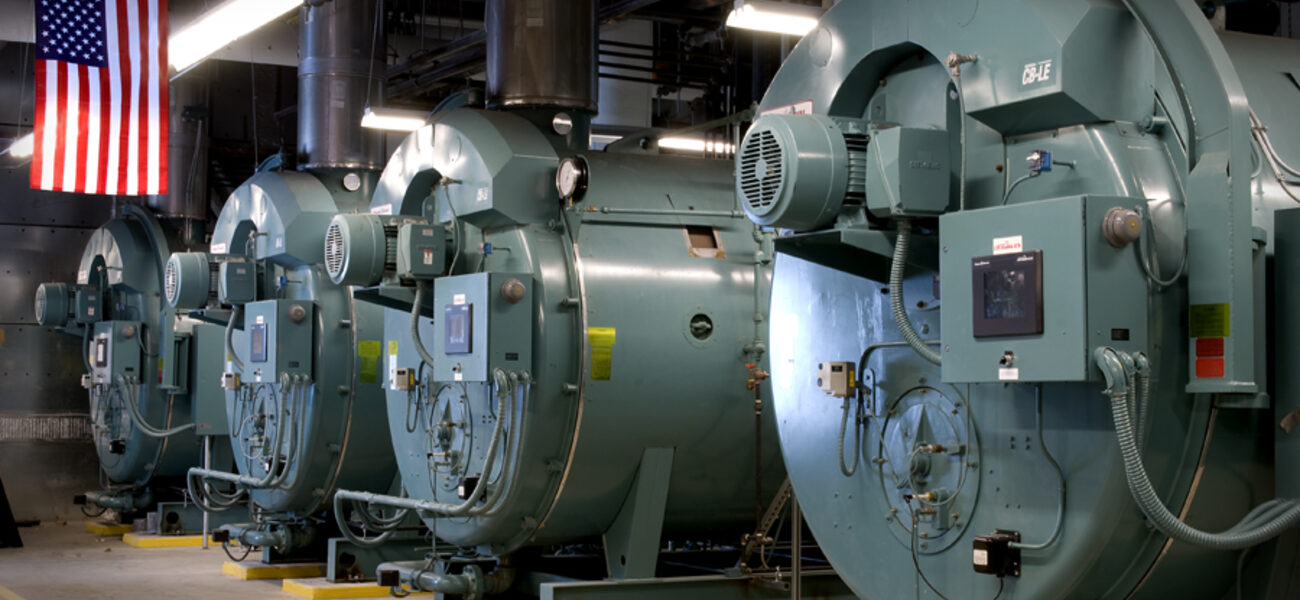

“Third-party developers are always thinking about adaptive reuse. They are underwriting the space for the second or third tenant, not the first,” says Kane. “Flexibility is starting to be realized in some of the building systems as well. We share mechanical systems among tenants, so they are not investing in their own air handling units and boilers and chillers.”

Avoiding Pitfalls and Surprises

There are numerous details to examine and options to consider when entering a lease agreement. Institutions can employ lawyers, architects, engineers, and even contractors to help with the evaluation and decision-making process. Brokers on both sides of the transaction can assist, as well, and some potential tenants employ real estate advisors.

Tools to utilize and factors to consider when comparing leased spaces include:

Landlord/Tenant Scope Matrix – An item-by-item listing that spells out which party is responsible for various structural and mechanical systems.

Rentable Area Measurement – A lease agreement for 20,000 rentable sf could actually total 10 to 20 percent less of programmable research space. Rentable space measurements include a tenant’s share of spaces like lobby areas. How the space is calculated can vary from landlord to landlord. Building efficiency can affect actual space as well. “It’s important to understand how the measurements are made so tenants can compare between buildings they are considering,” says Leary.

Exclusive Shaft Areas – Researcher laboratories require shaft space for both exhaust and other building services. Landlords differ in how they allocate such space, and tenants should establish up front if a building has enough shaft spaces for all potential tenants, or provisions for adding more without disrupting workflow. Some landlords will “rent” shaft spaces and should say so in the lease, says Leary. “This is another example of how space can end up being smaller than you think. It’s also a good idea to have a pathway to the roof or wherever mechanical services are located. If buildings are well-managed, there should be provisions for finding those pathways.”

Metering Matrix – With lab leases, tenants usually pay for their own utilities since usage is not always equal. To ensure fairness, establish up front how utilities are delivered and how costs are controlled and billed. Newly-outfitted facilities may have sophisticated meters, but many older buildings don’t, so in older buildings it’s “buyer beware,” notes Leary. “Memorializing these agreements in the lease—specifying each utility and how it is controlled and measured—benefits both parties and avoids disagreements later on,” adds Kane.

Tenant Design Manual – Landlords often put together a document with guidelines for build-outs, and these standards can affect tenants’ costs. A well-designed tenant manual goes hand in hand with the tenant/landlord matrix in establishing specifics up front and helping potential tenants choose the best option. It also shows that landlords have a well-run building.

Premise Drawings – These documents go even further than the rentable area measurement in showing the specific spaces allocated to each tenant. Asking for the drawings up front can help tenants avoid misunderstandings. The documents can also be used to establish “no-fly zones,” which are areas reserved for future tenant work, such as piping and utilities, so that these items can be added without disrupting other tenants.

Utility Capacity Chart – This measurement is sometimes combined with the metering matrix or landlord/tenant scope matrix, or can be a separate chart in the lease that gives design standards for each floor. It spells out the building’s capacity for utilities and provisions like airflow, and how much is available for each tenant. This is important when an institution is comparing different leasing options; one facility may have cheaper rent but not enough airflow capacity, which would raise the cost for the tenant, notes Leary.

Energy Management – Informed consumers should ask the landlord how energy usage is managed, especially if they are paying utilities. This includes the age of the systems (which speaks to efficiency), and the human side—how energy systems are operated/controlled. Energy management plans can also help landlords and tenants better control consumption and reduce costs, says Leary.

Leasing and Development Deal Options

Leasing and development options fall into four categories:

- Build to Suit – The institution partners with the developer to build the building it wants.

- Sale Leaseback – Arrangement where the property owner sells the property but agrees to lease it back from the purchaser for a specified time period.

- Building Lease – A standard agreements for renting space in an area.

- Ground Lease – The institution leases a piece of land for a set time period; any buildings/improvements on the land return to the property owner at the end of the lease term.

Standard building leases have four types: triple net, gross, turnkey, and tenant improvement (TI) allowance. In a triple net lease, all the operating expenses are passed through to the tenants, so they are motivated to minimize the operating costs of their space, says Kane. This option is popular among research institutions, because their energy usage is so variable depending on the type of research.

Gross is more prevalent in an office environment, where costs of utilities can be split equally because they don’t vary much between tenants.

A TI allowance is a budgeted amount of capital given to tenants for capital improvements. Tenants can hire their own design and construction teams, and typically use the allowance for equipment or structural modifications, says Kane. There is usually a timeline over which the allowance can be spent, providing additional flexibility.

“It allows tenants a little more control; it doesn’t cede all control, as the landlord will often require a review of the modifications,” he adds.

With a turnkey lease, the landlord undertakes the design and construction in accordance with specs agreed to by both parties up front. This arrangement is good for institutions that don’t have design and construction capabilities and/or the desire to handle these aspects. In both TI and turnkey arrangements, the tenant’s cost is factored into the rental rate.

Typically, TIs don’t cover 100 percent of costs, and institutional tenants can also utilize sources of capital outside of the lease arrangement, such as bond financing, grants, or endowments.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) used a TI leasing arrangement to consolidate 13 different research locations into one coveted location in Boston. The Harvard-affiliated teaching hospital had the financial capability to build a new facility, but a developer owned the land.

The developer had investors willing to commit to a facility whose scale (18 stories with six stories of underground parking) surpassed BIDMC’s initial needs, explains Kane, leaving open the option for BIDMC expansion or the addition of other tenants. The results proved to be exactly what BIDMC had hoped for—the resulting Center for Life Science, located in the heart of the Longwood Medical Area in Boston—attracted tenants like Pfizer and Children’s Hospital Boston. The tenants are collaborative partners and customers for some of BIDMC’s services, he adds.

“That building more or less defined a new way of structuring lease transactions, in that it was a high-rise building in an urban environment higher than the typical life science building, and required a lot more detail in the leasing process.”

Much more information was required up front, he adds. Architecture and engineering teams for the building owner and tenants collaborated to work out issues ahead of time.

“The process was longer than with a typical office building, but a lot shorter than building your own facility from scratch.”

In Conclusion

Research companies and academic institutions considering leasing should keep in mind that the options are increasing, but leasing does not make sense in all circumstances, concludes Leary. Lease and development structures vary, so it is important to consult with people who are knowledgeable in the field to help evaluate options and look for hidden costs.

“Translating your needs into what landlords have to offer, and making a good comparison, are key. It is a challenge to leverage different options because you’re not always comparing apples to apples,” he adds.

By Taitia Shelow

This report is based on a presentation Leary and Kane gave at Tradeline’s 2013 International Conference on Research Facilities.