The California Institute of Technology uses facility condition assessment and data-driven analysis to determine the best investment strategy for limited recapitalization funds. Combined with the institutional discipline to demolish or mothball buildings, Caltech minimizes costs and maximizes immediate functionality, while making funding decisions that support the institutional mission.

For the past decade, higher educational institutions have been building millions of square feet of new facilities, the second huge construction boom in the past 50 years. This wave of new construction peaked in 2006, but institutions now face a greater, looming problem: These massive facilities portfolios are aging and becoming more costly and less effective spaces, even as facilities from the post-war boom increasingly need extensive investment. Even so, many institutions continue to prioritize building new space over renovations and retrofits.

Caltech has another solution: Invest in significant renovation and modernization of existing facilities, giving old, rundown buildings that are well past their usefulness the opportunity to begin a new life as a modern science building. The Linde + Robinson Laboratory, for example, was one of three astronomy buildings constructed in 1932 as incubators for the 200-inch Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory. After a $35 million renovation, it is now the home of the Linde Center for Global Environmental Science, a LEED Platinum building and one of the most energy-efficient physical science labs in the country.

“We gave an 80-year-old building a new life,” says Jim Cowell, associate vice president for facilities at Caltech.

Dealing with Data

In order to make data-driven decisions, Caltech first has to collect the data. To do that, it contracts with ISES Corporation, a facilities condition assessment service, which conducts on-going assessments of the Institute’s facilities.

“They come to the campus every year and look at about one-fifth of our buildings” says Cowell. “From this we get a written report and asset data that can be mined to help us make better investment decisions.” In addition to detailed condition assessment of building systems, the ISES reports provide Facilities Condition Index (FCI) data for every building on campus.

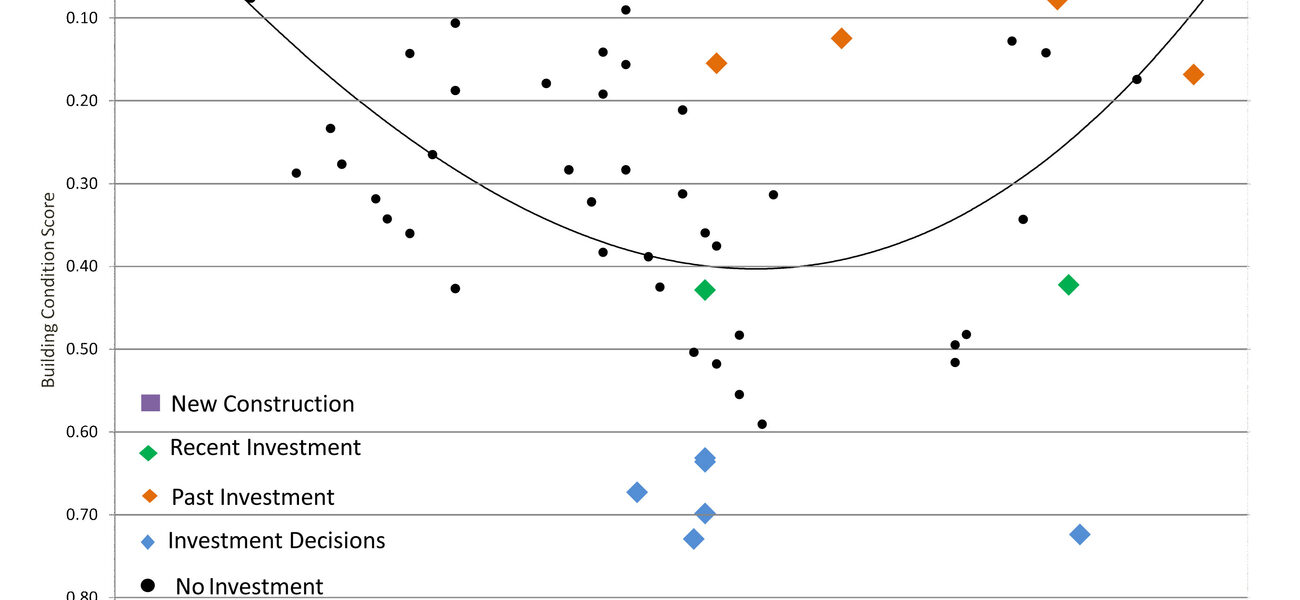

The FCI is a measure of the condition of a building relative to a replacement building with the same functional capacity. It is calculated as a ratio of the capital renewal cost (investments required above the annual maintenance and operating cost to return the asset to a reliable original condition) and the current replacement value (CRV). As a building’s condition deteriorates with time, its FCI increases. The suitability of a building to the institutional mission is determined by this benchmark.

Why Smart Funding Matters

“We never have enough money,” says Hickling. “We are always going to be about number three on the list in terms of trying to maintain the facilities. Recruitment of faculty and student aid are core things that the institution is dealing with, and those are going to get first dibs at the trough.”

Dealing with limited funding makes it important for institutions like Caltech to assess whether a building is meeting its mission requirements. When a building’s output has fallen so low that it no longer functions as a high tech science facility, for example, the time has come to decide its fate.

“When institutions need modern space, there are two ways they can get it,” he says. “They can either go out and build a new building, or they can repurpose some of the space they already have into what they now need.”

Caltech’s recapitalization strategy focuses on renovating and renewing existing spaces, even though new construction is frequently the easier option, as long as you have land and a willing donor. “The problem is, buildings are the gifts that keep on taking,” he says.

Every facility on a campus costs on average $6.50-$10 per gsf annually to maintain, not including utilities. That figure is constant, whether a building is new, with high functionality and a near-0 FCI, or old, inefficient, and in need of repair. When a campus gets overbuilt, although it gains new facilities, its older, underutilized facilities still represent a significant drain on the institutional finances.

“We think Caltech’s strategy in the long run is a better strategy simply because it matches up much better the amount and type of space needed to support the institutional mission, with responsible portfolio management,” says Hickling.

The Death or Rebirth of a Facility

Hickling stresses the need to apply total cost of ownership—the total cost of a facility to the institution over the life of the building—to an entire facility portfolio.

“The total cost of ownership of the institution’s portfolio will continue to climb decade after decade if the institution adopts a strategy of building new space whenever it’s needed and never pruning out the old space by demolition or repurposing,” he says.

Employing Caltech’s strategy requires that the institution be data-driven. First, institutions need to know how much space is needed and how it’s being used. Without understanding the use, an institution cannot know whether it is possible to repurpose it. Second, they need to know what it takes to repurpose a building, “Not just ‘Oh, this is an old building, and it’s rickety,’ or ‘This is a new building and it’s wonderful,’” he says. “Some buildings just can’t be repurposed very well.”

The third and most important requirement of this strategy is an institutional will at all levels to make necessary decisions about the fate of a building, even if that means demolition. “Understanding the real cost of space is particularly important as institutional expenses come under more scrutiny. The revenue line for higher education is not going up. You can’t build your way out of this problem,” says Cowell.

Cowell identifies a number of buildings on the Caltech campus as “investment decisions.” These buildings support important academic functions, but facility conditions are beyond even a deep renovation. “People might say that these are just broken down buildings, but they are investment decisions because we have made a decision not to make a major investment in these buildings,” he says.

Buildings set for demolition are put on a Do Not Maintain list, unless they are still occupied. Those that are will receive only emergency maintenance until their functions are relocated. Nonfunctional historical buildings or other buildings that cannot be torn down are simply mothballed. Their façades are kept presentable, receiving new coats of paint, for example, but they will remain shuttered until institutional need or external funding appears to repurpose them.

Buildings more often are given a new life. Caltech took a 1970s computer science building and did a whole-building renovation, leaving intact only the original concrete frame, which was seismically upgraded. Because the square footage has changed little, the annual maintenance costs have not risen. That building is now LEED Platinum certified and serves as the home for the Resnick Sustainability Institute and the DOE-sponsored Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis. These sustainability gains mean that the building’s energy costs are actually lower than in its previous incarnation, while its facilities have been adapted to accommodate the needs of future researchers.

The Caltech retro-commissioning program also supports recapitalization funding in novel ways. Retro-commissioning is returning a facility to its original design performance or better, normally through energy retrofit projects that reduce energy costs. Caltech “borrows” funds for these projects from the Green Revolving Fund created with endowment money, then “repays” them with measurable and verifiable energy savings from these improvements. At the same time, a good portion of the work eliminates deferred maintenance and contributes to recapitalization efforts.

Hickling stresses that this strategy of data collection is not the only way to assess the relative viability of facilities and determine the proper investment to make in them, but it is the strategy that works best for Caltech. The important thing, he says, is to pick a strategy that works for your institution, and then commit to doing it.

By Braden T Curtis

This report is based on a presentation by Hickling and Cowell at Tradeline’s 2012 College and University Science Buildings conference.