The idea of a workplace means something very different today than it did five years ago, before the pandemic. “Office occupancy has changed, and it’s not going back,” says Melissa Marsh, founder and executive director of the workplace innovation and real estate strategy firm PLASTARC. “Companies need to understand that environmental experience, including the sensory aspects of a building and its technology integration, plays a key role in driving occupancy rates and influencing employee performance.”

Marsh says they remain far below both pre-pandemic average occupancy rates and even further below the intended capacities of commercial real estate buildings. “When people say that current occupancy rates have reached 60 or 70 percent, it’s important to realize that those figures typically are calculated against pre-COVID occupancy rates,” she explains. “But we did not have full utilization of commercial building capacity before the pandemic. On average, across the country, commercial building spaces are now being used only about 30 percent of the time.”

Marsh notes this massive underutilization of space represents a crisis in terms of sustainability. “We can release a significant amount of this space and find other things to do with it,” she says.

In fact, Marsh expects that many commercial buildings will be repurposed. She points out that most corporate leases run for five to 20 years, and that we are only now approaching the first wave of post-COVID lease expirations.

But how much space companies need now is only one piece of the equation. Organizations also have to consider how that space will be used, along with which features and amenities it needs to have. “We are now seeing many companies have two major realizations,” says Marsh. “First, they probably need a lot less office space than they did in the past. Second, and just as importantly, we are seeing the majority of office space shift toward being social, collaborative, interactive, and rich in technology.”

Marsh is quick to emphasize that collaborative spaces do not necessarily have to be open spaces. “The goal is to give people more control over how they spend their day in the office,” she says. “Even on days when employees come to the office to collaborate with their teams, they may also need to be in a meeting with remote colleagues or they might even need to give a virtual presentation. So, the collaborative spaces could have a lot of pods or phone booths where people can go to perform these types of activities. This is a key point to remember—that social and collaborative spaces can promote learning and connection without being entirely open.”

Improving Return on Commute

While some organizations have gone fully remote and others have mandated a full-time return to the office, many companies have landed somewhere in the middle of the spectrum with a requirement that employees spend one or several days in the workplace each week.

In these hybrid organizations, many roles do not require on-site work, and most groups, including leadership and executive teams, are enabled to work from anywhere. Hybrid companies typically invest significantly in technology to support both remote work and asynchronous collaboration, enabling people to work on the same thing at different times and often in different locations. Hybrid firms aim to achieve inclusivity and learning without relying too heavily on physical spaces, so cultural events and community rituals are often defined and organized to include both digital and in-person events.

If employees at hybrid organizations can get so much done remotely, that raises the vital question of what employees should be doing in the workplace that’s different from what they do elsewhere. “Employees are expressing a desire for purposeful presence,” says Marsh. “Every day, employees tell us, ‘I don’t mind coming into work—I just need a reason.’ They don’t want to be asked to do the same things, perhaps with less technology or in a more distracting environment than they have at home. They want employers to give them a reason to come in and make the workplace experience worth the hassle of the commute.”

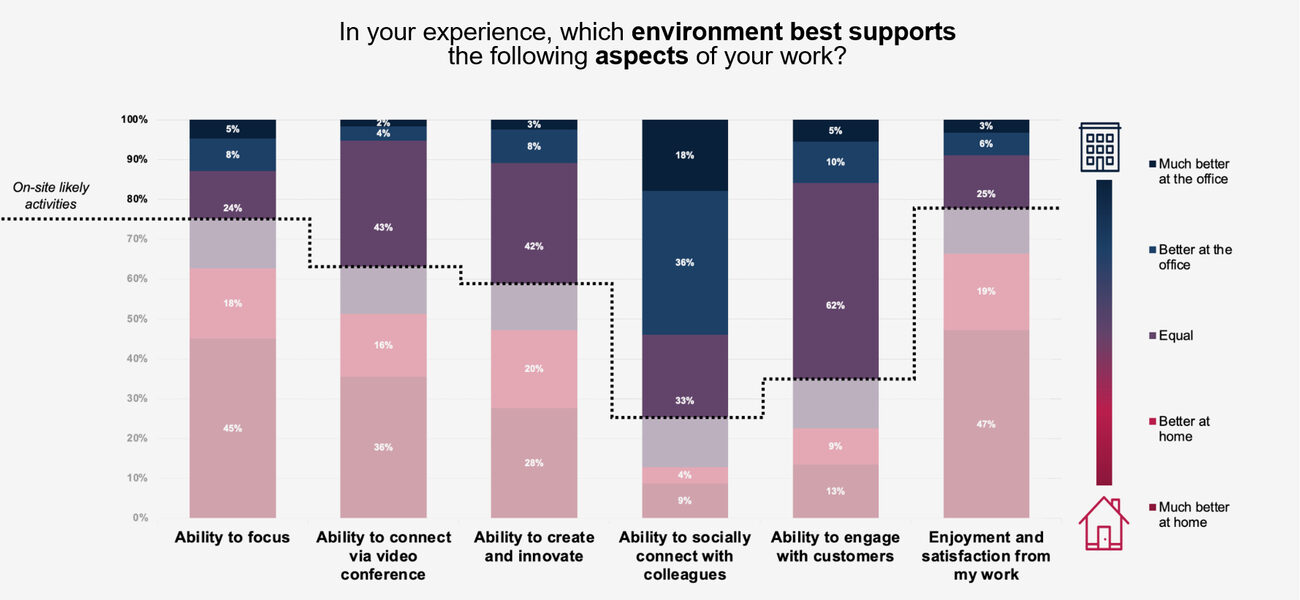

In fact, PLASTARC’s research shows that employees are much more likely to say that working from home gives them an ability to focus better, be more creative and innovative, and obtain more enjoyment and satisfaction from their job.

On the flip side, surveyed employees were far more likely to say that workplace environments were better for connecting socially with colleagues. Along those lines, 41% of employees said that knowing most of their team would be in the office on a specific day was a factor that drove them to work on site. That’s nearly double the percentage of employees who say they work in the office because their leaders expect them to do so.

“People are coming to work to see and be seen,” says Marsh. “From an employee perspective, the most important workplace amenity is one another. So, to the extent that companies decide to have mandates requiring employees to be in the office a certain number of days per week, research shows that such mandates are most effective when teams decide which days to come in, as opposed to having organization-wide mandates.”

The Powerful Appeal of Multisensory Factors

While some people call it hot-desking, hoteling, or shared-desking, Marsh prefers the term activity-based working (ABW) to denote a workspace that gives employees the power to choose what spaces to use on a given day or at a given time based on the activities they are doing.

“Thanks to all the sensor systems that are now in most workplaces, we can gather plentiful data on which types of spaces are most popular and well-utilized,” says Marsh. In fact, PLASTARC conducted research on a wide range of space types and found that the spaces used most often were those that scored high on a list of human environmental performance factors.

These factors were grouped into three categories:

- Collaboration support factors, such as whether a space was bookable and whether people inside and outside the space could see each other

- Comfort and concentration factors, such as whether employees could adjust the temperature in the space or control ambient noise

- Wellness factors, such as whether the space offered access to daylight and outside views and contained plants.

PLASTARC assigned spaces letter grades of A to F based on whether they offered these 10 features. The company then looked across all categories of spaces and found that A-rated spaces with the most human environmental performance factors were 10 times more likely to be occupied than F-rated spaces that offered the fewest human factors.

“Our research shows that workplace desirability depends on providing multisensory factors that align with employee expectations,” says Marsh. “This illustrates the power of design to influence whether spaces are utilized.”

Given the neurodiversity in any workforce, Marsh says it’s important to give employees a diverse range of spaces. A space that one person finds lively and stimulating, for instance, could be overwhelming to an employee with different acoustic comfort levels.

Leveraging Technology That Employees Bring to the Office

Marsh suggests that companies can give employees more control over the workplace experience by focusing on software rather than tech hardware. “I think you can assume that employees will come into the office with at least one mobile device,” she says. “So why install expensive physical equipment that will be immediately outdated when you can leverage the technology in the mobile devices that employees bring into the space?”

Instead of trying to integrate everything in the back end of a smart building, Marsh says companies can bundle multiple functionalities into a mobile app that lets employees reserve workspaces, see who is using a workspace at a given time, and adjust the temperature in a room.”

“Pushing this functionality to an app not only provides a touch point for the person, it also solves a lot of technical challenges in the smart building world,” notes Marsh. “It also gives companies a rich stream of quantitative data they can analyze to see how employees are using and experiencing the workplace.”

Marsh encourages companies to develop their own research programs to see which types of work environments are most desirable and well-utilized. “This data may show that some spaces are underutilized, which could inform decisions on improving efficiency by adjusting the company’s office footprint in a way that lowers costs, saves energy, and reduces carbon emissions,” she says. “It can also reveal which spaces are most popular and why employees use those spaces, which in turn can help you optimize the work environment to deliver a better user experience, increase productivity, and improve employee well-being.”

By Aaron Dalton