When the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), began to develop a new vision for its historic urban campus, they knew they wanted a high level of stakeholder engagement. The team that came together to work on the Parnassus Research and Academic Building (PRAB) called on elements of Lean construction, including Gemba walks and journey mapping, as part of design thinking, to empower users to co-create the spaces in which they will work.

The new facility—a 310,000-sf space in a dense urban environment—is now under construction, but the planning process began in 2021. The university expects to move researchers and other users into the space in 2028.

“The vision for the project is that the building will be a catalyst for campus transformation,” says Deepa Balgi, principal on the project, and science + technology princpal and practice group leader at HGA, architect of record, working in partnership with design architect, Snøhetta. “It will be people-focused and mission-driven. It will accelerate impactful innovation, discovery, and learning. It will foster thriving collaborations across multiple diverse communities, and inspire all who enter for generations to come.”

The Big Room

Guided by an ambitious vision, the design partners prioritized upholding Lean Design and Construction principles by assembling a team of committed individuals and organizations from the project's inception. “We went through a very rigorous interview process with scenario-based interviews so that they could determine who would work best with (the principles),” says Mark Rothman, principal design manager for design-builder Hensel Phelps, who worked with the team most intensively in the early design stages.

Rothman notes that the progressive design process they used is more collaborative and less litigious than the traditional design-bid-build system. The team brought on tradespeople—mechanical, electrical, and plumbing firms, among others—from the start. “It allowed designers and builders to make decisions together as a team,” he says. “The hope is that you’re going to reduce the schedule. We started doing physical work in the field long before we had finished design development.”

To keep everyone coordinated, the university set aside a space—not just a conference room or an office, but a space big enough to hold more than 200 people from 15 consulting firms and 35 total firms, including trade partners. Its official name was the Integrated Center for Design and Construction, but most people referred to it as the ICDC. There they held weekly “pin-up” meetings with campus leadership to report progress and receive feedback. Team members collaborated using software-based whiteboards (VPlanner and Miro), but also physical boards and sticky notes in the ICDC.

They particularly relied on one Lean method called the Gemba walk. This involves walking through a workplace, asking people about their tasks, and looking for ways to improve productivity. (The name comes from a Japanese word for “actual place.”)

“We didn’t know exactly who was going to be moving into the building, but we did have representatives from the six sciences that they had identified that would be moving in,” says Balgi, and we were able to observe teams in those sciences to inform our work. “We reached out to principal investigators (PIs) and researchers in 10 labs and asked for a tour,” says Amin Mojtadehi, design innovation manager at HGA.

Rothman notes that they needed to move beyond the surface in these walks. “We ask them, ‘Don’t give us a tour of the space, give us a tour of your workday,’” he says. “That is what Gemba is curious about. We want to know what the workflow is in the context of a space. We had to follow them; they would touch spaces multiple times during different parts of the day.” For example, the team realized that on an average day, a researcher takes between 5,000 and 10,000 steps because supplies and plasticware are scattered in various locations.

“We asked ourselves, ‘How might we provide storage to remove the need to run around gathering supplies?’” says Mohtadehi. That research helped inform the design of the lab spaces in the new building.

Design Thinking

Another key methodology the team used in tackling their complex challenge was design thinking. This is not specifically a design system, but rather a way of solving problems that can apply across multiple disciplines. Key elements of design thinking include framing the problem by asking the right questions; empowering the users of a product to co-create or change it; and focusing resources on the items that will have the most impact.

Mojtahedi says, “Design thinking is a method for creating organizational change; and it elevates users from research and design subjects to research and design partners.”

One tool of design thinking is “journey mapping.” This involves taking one key element of a complex process—a physical object, a document, a person, an idea—and following it from where it enters the organization through every step of its path. Like some elements of Lean, design thinking starts by mapping the current workflow of one person whose work engages with the system being considered. Researchers also ask for people’s experiences and even emotions.

For instance, Mojtahedi tells a story of a workplace where many people were stressed and rushed in the mornings. “We asked ourselves how we might make the employees’ morning relaxed and delightful, as opposed to rushed and stressful. The solution was to create a coffee shop at the point of entry to the workplace, where people walk in to the aroma of coffee and baked goods, and the sound of their colleagues chatting, as opposed to a sterile reception desk where they have to sign in.”

The resulting process was not purely Lean, nor purely design thinking, but pulled on methods from both paradigms with a focus on making sure stakeholders were informed, engaged, and bought in to the changes the new building would bring.

Engaging the Stakeholders

Throughout the process of designing the new building—which will also include space for the nursing school—the team made a point of reaching out to stakeholders and engaging them in “co-creation” of the spaces to come. They spent 5,000 hours in stakeholder engagement meetings, reaching out not only to faculty and researchers, but also to facilities staff, ergonomics professionals, and accessibility experts.

While the team did use some standard surveys, many of the co-creation decisions were made in collaborative workshops, which brought together the people who were likely to be using the new building. (Now that the university has chosen the 44 principal investigators who are moving in, HGA will also be working on a change management process to prepare them to make the most of their new spaces.) The workshops were seen as a more inclusive and collaborative approach, bringing together stakeholders in small groups instead of larger town halls.

“Deepa and other folks on the project really pushed this idea of stakeholder engagement and turned it into something real,” says Mojtahedi. “People were hands-on, building on each other’s ideas.”

The workshops also confronted some stakeholders with the collisions between their priorities and other people’s, and the results were sometimes illuminating. Balgi tells of one sample decision: whether to put write-up desks inside the labs or in separate office areas. While faculty were divided about 50-50 on the question, the researchers were almost unanimous that they wanted the desks outside the labs. Because they had spent time learning about one another’s perspectives, “they understand the constraints, the reason why one solution works better than another,” she says.

The Finished Product

“Our charge was to create a universal lab where any PI from any of these sciences can function on day one,” says Balgi. “We have flexibility built in.” Lab spaces reflect the results of all those hours of stakeholder research, but also priorities such as collaboration spaces and creating positive experiences for the building’s users—yes, there’s a coffee shop at the entrance.

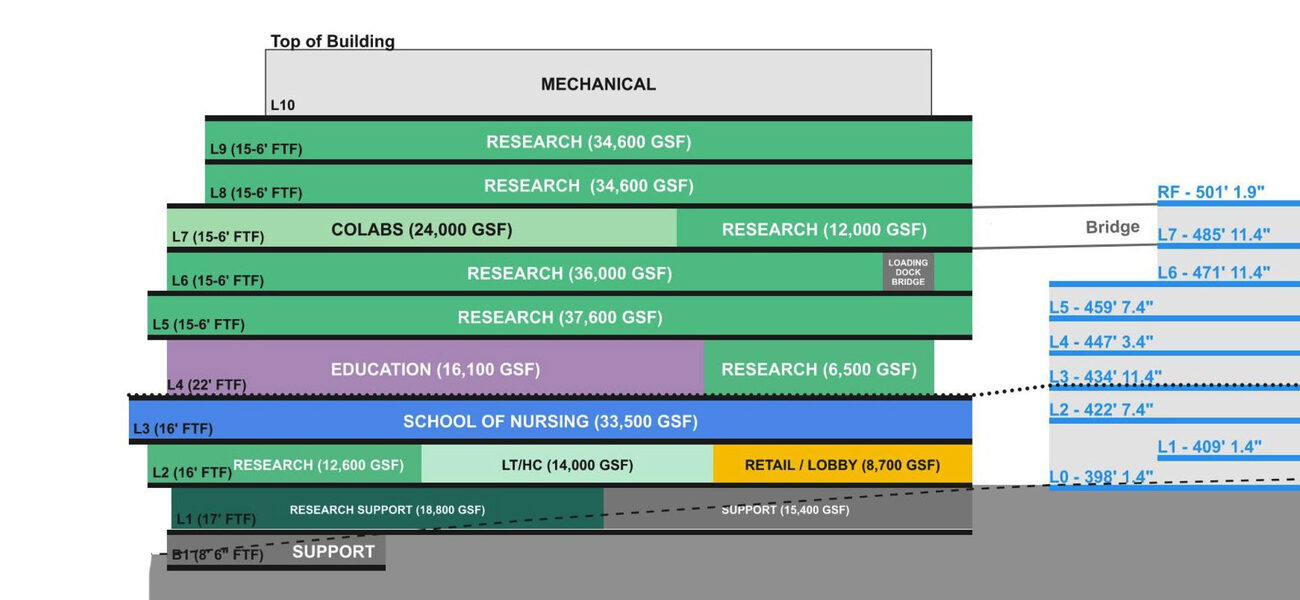

The building is stacked nine stories high, with mechanicals on the roof and support spaces in the basement. The nursing school occupies the third floor, and a section of the fourth floor is set aside for classrooms and other educational needs. On the seventh floor, a skywalk will connect the new building to the adjacent Clinical Sciences Building, providing a connection to the rest of the campus and extending all the way to the new hospital on the east end.

“The fortitude of the design team, Hensel Phelps, and the university to say ‘we’re going to deliver this project’ is a testament to how well the team works together,” he says.

Mojtahedi sums it up even more succinctly: “People support what they create.”

By Patricia Washburn