Virginia Commonwealth University needed new space for math and science classes. When prototypes and stakeholder feedback indicated the student experience was top priority, they changed their planned two-stage facility to a single STEM building focused on making it easier for students to learn in the ways that suit them best.

There was no doubt that the Richmond school needed the room. “It was a bottleneck. We didn’t have enough lab space to break the bottleneck to get students to graduate on time,” says Richard Sliwoski, associate vice president of facilities management for VCU.

At the same time, the 168,000-sf facility would need to slot into a historic district within the crowded urban campus. The original plan was to create one section full of classroom space, then a second phase for administration offices.

“For each project, we work closely with the end users to design and construct spaces that meet their needs and ultimately support student success,” says Lauren Bailey, a project manager at the university who worked on this building. By involving stakeholders early in the process, the team learned that student learning space was more important to the university’s long-term goals than the space for administrators, who already had offices elsewhere on campus.

The Math Exchange

The new plan focused on creating spaces where students—many of them minority, first-generation, and international learners—would want to engage with math and science topics.

One of the most innovative spaces is the Math Exchange, a large space completely devoted to math learning. Bailey credits Glenn Hurlbert, Ph.D., a math professor at VCU, with advocating for the central math learning space, often sliding into meetings on the rollerblades he uses to navigate the campus. “He is really excited about math, and he wanted to have students learning actively,” she says. “We had a prototype of that open learning kind of space, and it developed based on that, but also on his energy and love of math.”

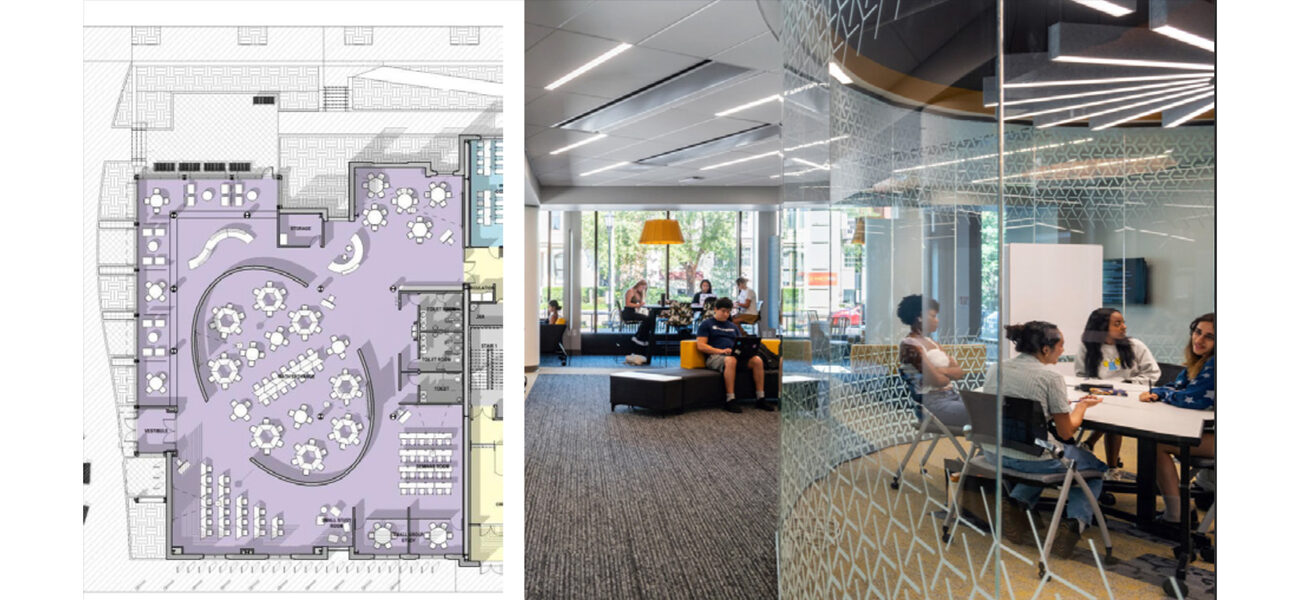

The space reflects mathematical concepts in ways the students can see. An elliptical space defines room for group work, with space for individuals and small teams along the outside and lighting radiating from two central foci. Bailey says the ellipse was originally planned as an oval—a less mathematically specific shape—but math faculty suggested that it be a true ellipse, and the architects made the adjustment.

The space has encouraged math learners to want to focus on their work. “The students do really love this,” says Bailey. “Students and faculty have developed a tradition of dropping their cell phones into a box when entering the area so they can work without distraction. They like that time away, to really be able to concentrate on what they’re doing.”

A Science Powerhouse

The STEM building provides the College of Humanities and Sciences with room for 10,000 students and nine departments. Two 200-seat classrooms are fitted with hexagonal tables, which encourage students to form small study groups and allow for flexible teaching modalities. As a design element, the ceilings reflect the shape of the double helix that makes up DNA, the genetic code behind all living beings.

In the laboratory spaces, interior glazing admits natural light and puts scientific work and learning on display. The building includes 32 wet and dry labs, each equipped with powered cubbies where students can charge their electronics while they experiment, plus a plant growth lab and a crime scene lab. Labs feature similar furniture and components, so they can be repurposed as program needs change.

As part of the focus on student success, a Science Hub brings faculty into the space for meetings with students, rather than students having to hunt down faculty offices. About 40 professors use the space to hold office hours. Sliwoski cites survey results showing that most students are more comfortable meeting with advisors in this space and many feel a stronger sense of belonging at VCU because of it.

Many students feel that asking a faculty member for help means they’re not smart enough to be there. Having this shared space for students and faculty eliminates the stigma of asking for help, because everyone is doing it. “There are a lot of first-generation students here who don’t know how to navigate the college scene,” he says. Making it easier for them to get help makes the experience better for everyone.

That’s part of a pattern of positive feedback for the new building. “The professors are telling us that students are coming to class more often. They’re not cutting classes often. They’re actually showing up to participate in what we’re doing,” says Sliwoski.

Stakeholder Engagement

Sliwoski and Bailey credit input from stakeholders with making the building better. One professor in particular, Sally Hunnicutt, became what Sliwoski calls the “golden thread”—someone who stayed with the project from start to finish, helping keep teams on track and reminding them of the project’s overarching goals. That continuity was particularly important as the project kept going under six different permanent and interim deans. Hunnicutt herself was promoted, from associate chair and professor in the chemistry department to interim dean for faculty affairs, but continued to be part of the building’s core team.

“She kept everybody focused, and she embraced the vision,” says Sliwoski. “Because she was there, she kept it all on track so we didn’t have any unfortunate changes during construction.”

The team made sure to include not only faculty and staff but also everyone connected with the building—including the end users such as housekeeping, maintenance, operations, engineering, safety, risk management, and campus police. “Being the facilities people, I can’t tell you how important it is to have my folks look at everything, from where they put access panels to the size of the access panels. It’s the details that will help you maintain the building,” says Sliwoski. “We’ve got to be able to change a light bulb without building a scaffold.”

Besides early meetings with stakeholder groups, the VCU team relied on results from prototype projects that tested some of the ideas they wanted to implement. In particular, the Math Exchange was the result of a prototype that went into operation elsewhere on campus before the project began.

Prototyping also informed furniture choices. “We found that the space challenges had to do with the faculty having to work around furniture, hindering their ability to interact with students,” says Bailey. “In the new building, we wanted to make furniture flexible and create interactive spaces allowing students and faculty to connect. We researched how new ideas for the STEM building would work by conducting pilots in existing buildings before incorporating them into the new building.”

Positive Results

Listening has paid off, says Bailey. The building’s manager told her, “I don’t have a bad thing to say about the building”—high praise from a facility manager. Likewise, Hunnicutt told Bailey she enjoys observing classes in the large rooms because she “can’t even find the professor.” Instead of lecturing from a limited space, faculty are actively supporting and participating in students’ collaborative work around the classroom.

The building fits into the historic district and includes a variety of warm and inviting student spaces, opportunities to display student work, green plants indoors, natural light and views to the outside. Throughout the building, study and collaboration spaces of various sizes respect the fact that not every student learns the same way. “Everybody’s got a different style for collaborating or just quiet time. Students appreciate what we’ve done here,” says Sliwoski.

The building has been open for a year, and the lab space bottleneck has greatly diminished. The Math Exchange has proven so popular that high school students use it when college isn’t in session. VCU’s science footprint is growing, with $464 million in sponsored research, a 71% growth over the last five years.

Sliwoski points with pride to the challenges this building faced. They began demolition of the previous building in June 2020, at the start of the pandemic, and dealt with a flood and supply chain issues as well as leadership turnover in the College of Humanities and Science. Yet they were able to bring in the project on time and turn $2 million back over to the state. “This has been very, very successful,” he says.

By Patricia Washburn