The life sciences sector is experiencing an era of unprecedented growth driven by a surge in both public and private funding combined with a post-pandemic sense of urgency and market opportunity. According to a report released by Newmark in January 2021, more than 36 million sf of new construction is expected to be delivered in the nation’s top 14 life science markets, as life science investments more than triple. While demand for life science and biotech facilities has been growing steadily over the past decade, the COVID-19 crisis heightened national awareness around the need for increased research, diagnostic, and domestic manufacturing capabilities. Investors are also seeing significant potential in the future of personalized medicine, genomics, and other life science-related fields, as emerging technologies and research disciplines converge.

It’s worth noting that the life sciences sector was already on a strong growth track well before the pandemic. According to Crunchbase, which provides market information on public and private companies, California’s life sciences sector received more than $4.95 billion in funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2019, prior to the pandemic. And, according to JLL, life sciences space in the greater Boston area grew from 17 million sf in 2010 to 27 million sf in 2020. Newmark also reported that Boston currently has 21 million sf of life science space in the development pipeline that will deliver by 2024. Despite all of the supply growth, at the end of first quarter 2020, Boston’s life sciences market had a real estate availability rate of only 7.3 percent (3.2 percent in Cambridge) while the San Francisco Bay Area had an availability rate of 5.7 percent (with 2.5 percent in the Mid-Peninsula region). According to Newmark, life science tenants in the Cambridge area are now expecting to wait almost two years for available space.

“I think the current surge of demand in the life sciences sector is a continuation of what’s been building for almost two decades,” says Chris Baylow, managing principal and leader of Science and Technology at EYP in Boston. “And it is really being fueled by personalized medicine and the convergence of technology. In the Boston or Kendall Square areas, for example, you’ll drive around and see Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft adjacent to the Genzymes and the Biogens of the world. So the intersection of technology and life sciences is just clearly evident as you walk down the street.”

“COVID has kind of increased the momentum behind what was already happening in life sciences, but it was already starting,” says Jane Baughman, technical director at EYP Architecture & Engineering in Austin. “Some of the clients I was serving before COVID were already seeing an increase of interest in genomic and diagnostic testing, which has become a really big part of healthcare. In fact, diagnostic and clinical testing is second to the OR in sheer square footage that it takes up in a healthcare facility. That’s how big it’s grown just in healthcare alone. And it really is being driven by the growth of personalized medicine.”

The pandemic is also creating research facility opportunities in the real estate market. More and more office employees are opting to work from home, leaving their former office space available for renovation into laboratories. An increasingly popular option, particularly for start-ups that have to ramp up quickly when they secure funding, is prebuilt labs constructed on spec to be ready to occupy as soon as a tenant is identified.

Pandemic Response

That said, response to the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly accelerated both institutional and investor demand for life science real estate, from wet lab and incubator space to biomanufacturing and R&D facilities.

“COVID has brought the topic of infectious disease back to the forefront,” says Tim O’Connell, director of HOK’s global Science + Technology practice. “There was going to be a natural increase in the life sciences sector anyway because there’s so much interdisciplinary work being done now. By that I mean that there’s a lot of discovery research out there, but then there’s also research in what I would call applied areas—engineering and technology moving into the life sciences space to create new therapies, better therapies, better research models, things of that nature. But COVID definitely gave it a boost. I think as the tech industry moves into life sciences, there is just naturally going to be an increase in activity. And there are all these companies, both big and small, working in infectious disease who immediately started to work on the vaccines, from AstraZeneca and Pfizer to Moderna—which is a relatively small company working with NIH. I think that speaks to the fact that technology now enables smaller players to play on the same ball field as some of the larger companies.”

The pandemic crisis also revealed the need for dependability in the domestic supply chain and the vulnerability of relying on overseas manufacturers. For example, there was a massive shortage of specialized testing swabs during the initial outbreak, because the best swabs were manufactured in Italy, which was hit especially hard early on. As a result, demand for GMP manufacturing space in Greater Boston is now the highest it’s been in over five years, representing more than 30 percent of current demand in the region’s life science marketplace.

Established and Emerging Clusters

The nation’s “big three” clusters of Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego continued to dominate the market in 2020. This is partially attributed to the fact that they are also home to the major research institutions that produce a steady pipeline of STEM-educated workers. With over 50 universities, multiple research hospitals, and more than $15 billion of VC investment over the past three years, Greater Boston remains the epicenter of life science activity in the country. According to JLL, the number of life science R&D firms in Greater Boston has increased by 51 percent over the past five years (to 1,983 in 2020). Boston’s life sciences market also had a sales volume of $3.2 billion in 2020 with high watermark pricing for premium lab space hitting $1,900 per sf and an average of $650 per sf. Likewise, sales volume in the San Francisco Bay Area in 2020 reached $3 billion with high watermark pricing of $1,000 per sf and an average of $570 per sf.

As demand for lab space and skilled workers increases, new clusters are emerging in other areas, including Houston, Denver, New York City, Chicago, Raleigh-Durham, and the Mid-Atlantic region.

“I have seen a fair amount of growth in the Washington, D.C., area, which is where NIH is located and where I happen to live,” says O’Connell. “Raleigh-Durham is another big emerging market. We’re also doing a very large project in Houston right now and potentially starting a second very large project there. And another one of the developers we’re working with has some very big developments they want to shift to Chicago.”

“The Texas Medical Center is the largest medical center in the continental United States, and they’re really branding this area as the third coast for life scientists,” says Laura Vargas, project director at EYP Architecture & Engineering in Houston. “They have been working over the past few years to create an entire campus just south of the Texas Medical Center called TMC3 that will be dedicated to convergence in life sciences.”

Houston’s TMC3 project is a $1.5 billion collaborative life sciences development currently being established with the goal of enabling the city to compete directly with Boston and San Francisco for medical research and discovery. When complete, it will feature a wide range of both shared and proprietary research centers, multidisciplinary laboratories, and healthcare institutions totaling almost 3.7 million sf of developed property spread across 37 acres. Denver is also coming up as a future cluster for life sciences, thanks in part to the 578-acre Fitzsimons Life Science District in Aurora, which is home to a diverse collection of biotech and life science firms that collaborate with University of Colorado and hospitals in the UC Health system. New York City, not traditionally known as a life science research cluster, is also maturing its capabilities. NIH funding to research institutions in the city has risen every year since 2016 and hit $2.2 billion last year. Manhattan’s Alexandria Center—which includes Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Accelerator Life Science Partners as tenants—is expanding its life sciences footprint by 550,000 sf that is expected to be completed in 2024. And a planned 1.1 million-sf redevelopment project in a former warehouse district of West Harlem, called the Manhattanville Factory District, will eventually provide another 600,000 sf of lab and office space.

The relentless search for lab and manufacturing space near the established life science clusters is pushing more construction and conversion activity to nearby suburbs and communities. According to JLL, suburban lab demand near Greater Boston is now double that of Kendall Square, as companies look for more industrial-zoned space in close proximity to Cambridge, including downtown’s Seaport District, as well as Lexington, Watertown, and Waltham. Likewise, in San Francisco, nearby submarkets like Emeryville, Berkley, Hayward, and Palo Alto are becoming hot new targets for conversion and redevelopment.

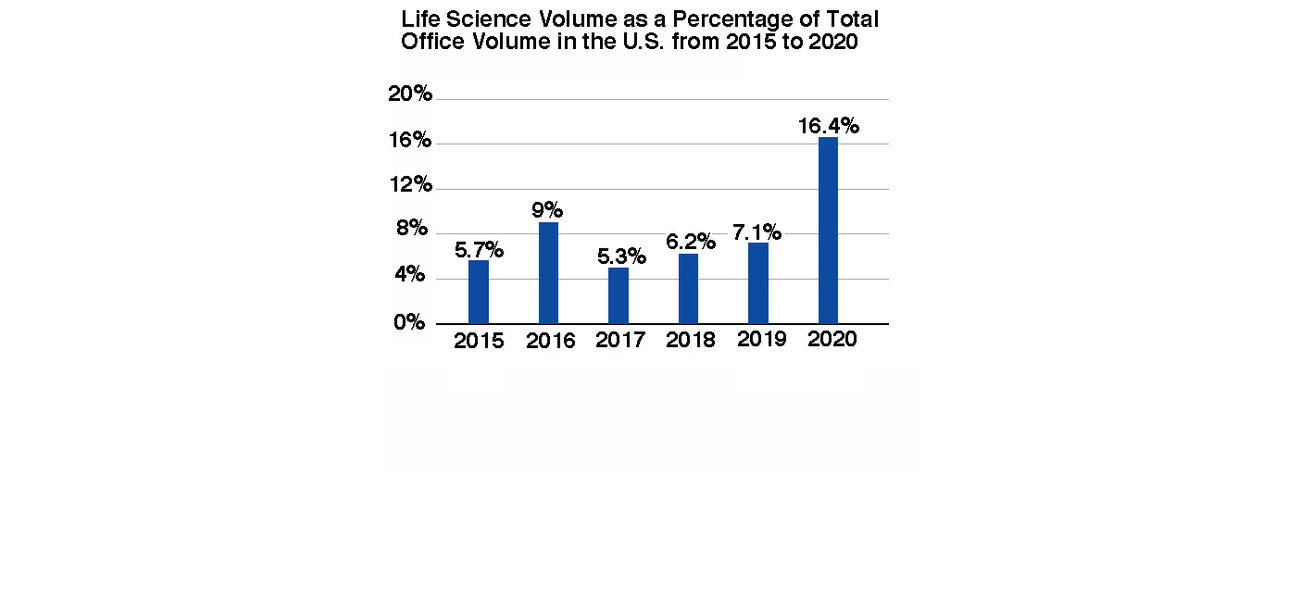

Another impact of limited real estate availability is the desire to convert existing commercial office and retail space into life sciences facilities. This trend is also being fueled by a mass shift to work-from-home strategies that are leaving many office spaces vacant, combined with real estate investment trusts that are reevaluating what the highest value use is for their office, flex, and industrial portfolios. Since life science tenants are looking for projects that can be ready within 12 months, space conversions are more attractive than new construction. According to Newmark, the volume of life science investment as a percentage of total office volume reached a record high of 16.4 percent in 2020, which was more than double the 2019 figure.

In the Boston suburb of Watertown, for example, the former Arsenal Mall is being reconstructed into 165,000 sf of lab space on nine stories, all on spec. Construction of the new 100 Forge building is expected to be completed in summer 2022.

“In Boston, we’re getting to the point where you have to knock something down to build something new,” says Baylow. “But there is a lot of commercial office space and retail space in the city where leases are coming available. More people are working from home now. And companies are questioning whether they should go back to an office headquarters, or let their lease expire and continue with a work-from-home model. This is creating a niche opportunity for looking at buildings that were not originally designed to support life sciences to see if they could be used for that purpose. Because, geographically, they’re in the right spots.”

Of course, converting office and retail space into wet lab and R&D space requires looking at a number of suitability factors, including column spacing, which dictates planning modules for research space, and floor-to-floor heights, which need to be high enough to accommodate the increased HVAC needs. Most life science tenants are looking for floor heights of at least 13 to 15 feet or more and prefer large, wide floor plates with robust load capacity that can support heavy wet lab equipment (100 to 150 pounds per sf). HVAC is also a big consideration, both for initial construction and ongoing operations. Most labs have single-pass HVAC systems, and many require a minimum of six air exchanges per hour with continuous exhaust ventilation.

“From a supply-side point of view, developers are looking for greener, more lucrative pastures,” says Trip Grant, Educational, Science, & Advanced Technologies principal at HDR Los Angeles. “Many traditional commercial and mixed-use real estate developers are entering the life science and biotech market to diversify their holdings and hedge against a changing retail environment. For example, Capri Capital Partners, the owner of the 43-acre Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza mall, one of the largest retail and mixed-use re-developments in Los Angeles, has been considering an adjacent 10-acre parcel for a 750,000 sf bio-science park. And San Diego State University, with their new Mission Valley Campus, is looking to develop sustainable funding streams by creating live/work bio-science parks in partnership with the industry.”

Just the Beginning

The rapid pace of growth doesn’t appear to be slowing down any time soon, as global tech companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Alphabet (parent company of Google and Verily Life Sciences) move into the healthcare and life sciences realm. The COVID pandemic has also increased awareness around the need for healthcare organizations and academic research institutions to invest in diagnostic testing and vaccine research capabilities. In addition to the massive influx of private investment in the sector, the NIH received $3.6 billion of additional federal funding in 2020 as part of an emergency COVID-19 stimulus bill, much of which will be allocated to support research into infectious diseases, vaccines, and diagnostics. The NIH has until September 2024 to distribute those funds, which will allow for more detailed planning and longer-term research activities.

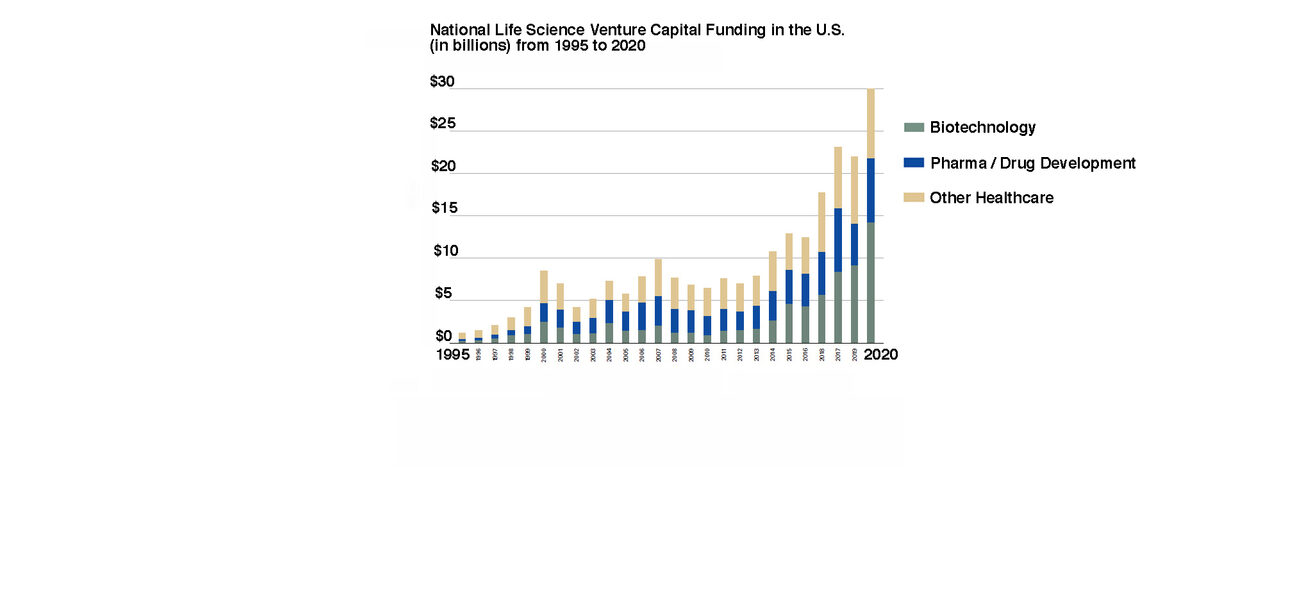

Despite the negative impact COVID-19 has had on the rest of the economy, VC funding in the healthcare sector remained strong, reaching a record $29.9 billion in 2020, which represents a 36 percent year-over-year increase. Biotechnology was the fasting growing vertical in healthcare, with VC investment increasing by 56.6 percent year-over-year, followed by a 50.2 percent year-over-year increase in drug and pharmaceutical investment. The largest deal in the fourth quarter of 2020 was a Series B investment round of $750 million for biopharmaceutical company Resilience, which was backed by Google Ventures, ARCH Venture Partners, and other investors. All of this means that, as the biotech market becomes more and more competitive, investors will start to look further upstream at smaller private companies with smaller valuations.

“Here in Austin, we’ve had some big players like Google, Amazon, and Tesla move in, and they’ve all delivered these upfront initiatives to start getting into the healthcare environment,” says Baughman. “How that happens, we don’t know yet, but we know the second tier will involve a lot of these small startup companies in the area that produce vaccines or plasma or other types of products related to bio. They’re all trying to see how they can integrate their next idea—most of which are based on diagnostic testing—into something bigger and possibly get it picked up by one of these big players that are all becoming active in this convergence of technology, healthcare, and science.”

“With companies like 23andMe getting into the space, large healthcare entities like the Texas Medical Center are beginning to see that diagnostic testing, which used to be kind of a flat line financially speaking, is becoming something they could actually turn into a profit center. People are now willing to pay for genomic testing, and there’s something like 800 to 1,000 identified genomic diseases that testing can determine you have, or have a biomarker for, just by getting your genome sequenced,” says Baughman.

“I don’t think we’re anywhere near the saturation point for life sciences,” says Grant. “I believe we’re closer to the beginning of the journey than the end. The investments in STEM education over the last decade, a new socially-aware breed of philanthropists, an evolving real estate market, and a decentralized work-from-anywhere approach all lead to new and exciting opportunities in the life science, bioscience, and biotech marketplace.”

By Johnathon Allen

Attend the Research Facilities 2021 conference in Boston this fall on September 27-28 to get the new metrics, facility features, and capital project strategies for the changes underway in high-technology laboratory and research work environments. The content of this conference has major planning implications for your research facilities, R&D workspace, and laboratory renovations, upgrades, and expansions.