While many campuses remain closed to undergraduate students, at least through the summer, researchers are beginning a phased return to their labs, with new safety protocols that include face masks and social distancing; guidelines for space usage and maintenance; and staggered work schedules. Institutions are requiring that researchers continue to do as much work as possible remotely, including writing, analyzing data, and conferring with colleagues. In order for research to fully resume, however, faculty need access to their labs, but they first must be trained in the new protocols and agree to adhere to them; failure to do so will results in the loss of lab access.

In March, most labs were hastily closed, and animals were culled from vivariums, as the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered colleges and universities across the country. Only the most critical research, which would suffer irreparably from a rapid closure, was allowed to continue. The reopening, by contrast, is occurring in a much more measured way, with lab facilities initially permitting 25-30 percent occupancy in each space, then scaling up to 50 percent. That is likely the maximum achievable density until the Centers for Disease Control revises its guidelines around maintaining a 6-foot distance between people.

How the reopening is managed varies from institution to institution. Harvard University, for example, places the responsibility squarely on the principal investigator to implement the university’s extensive reopening plan:

“The principal investigator (PI) of a research program—with detailed knowledge of workflow, layout, personnel, shared instrumentation, and program priorities—will work with his/her/their research group and departmental administrators to craft a plan to resume a program’s research activities … subject to departmental review… No new work can begin until a lab’s plan receives School and University approval. The PI … bears ultimate responsibility for compliance.”

Space Configuration and Occupancy

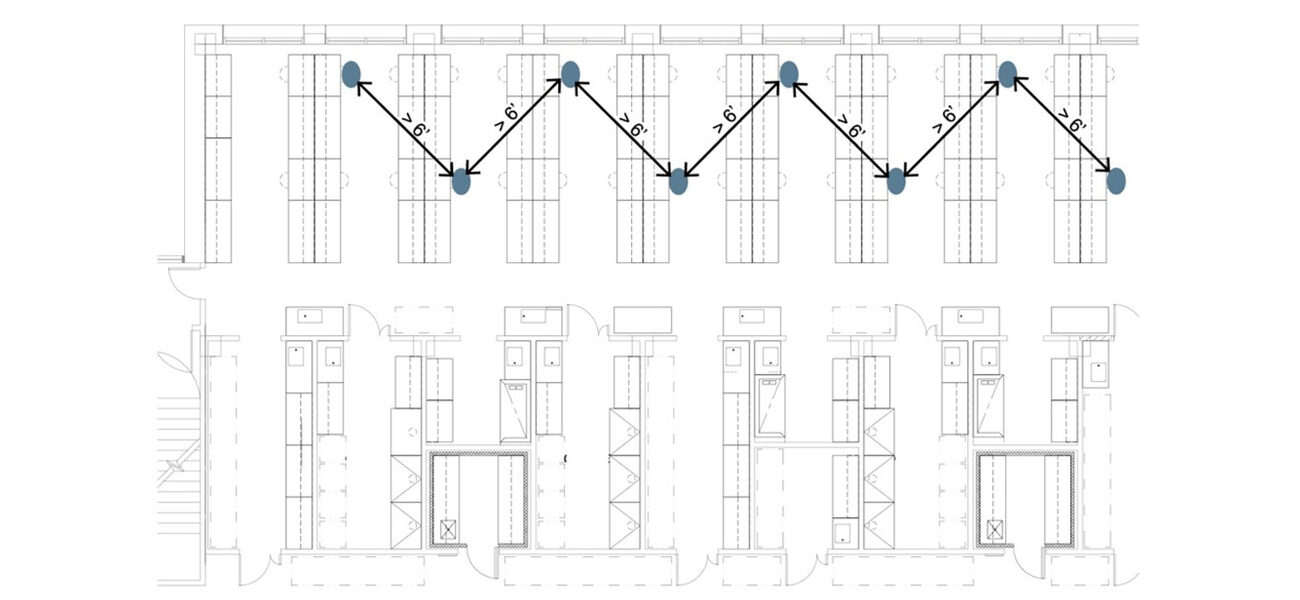

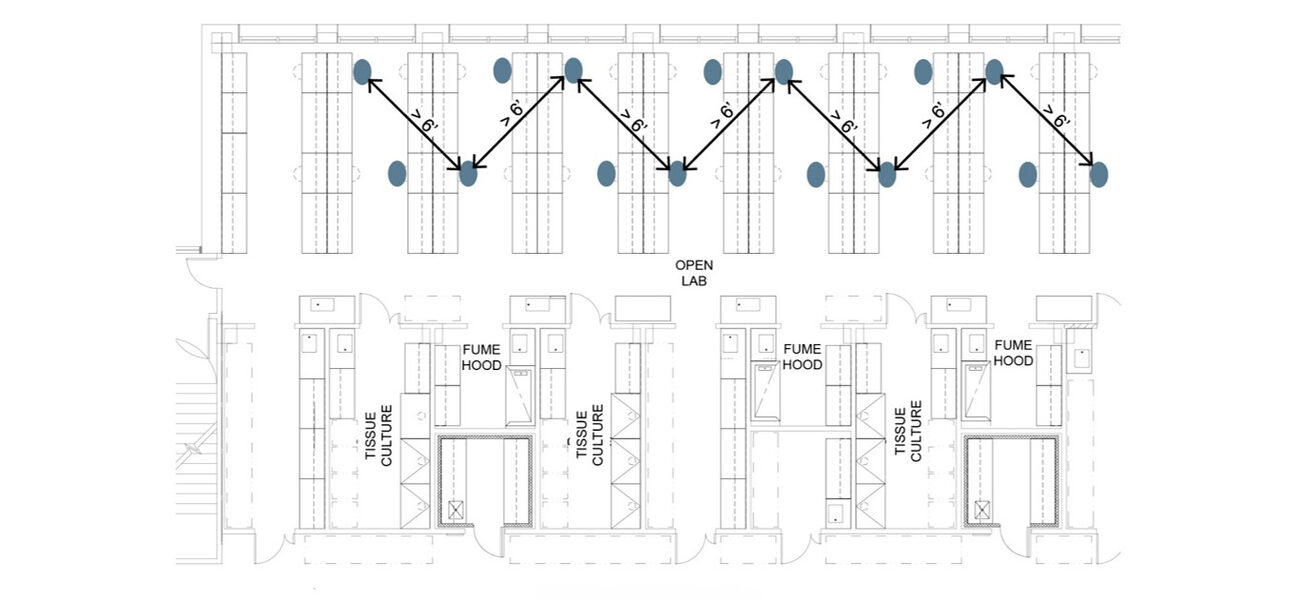

Perhaps the most straightforward changes in the lab environment are to the physical spaces. Anna Pravinata, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP, and Mamie Harvey, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, both principals at Alliiance, have developed guidelines to reconfigure lab space to maintain social distancing:

- Disperse lab workstations to avoid two lab techs facing each other or being in the same aisle.

- Install physical barriers, like clear acrylic or plexiglass, if separation is not possible.

- Reconfigure spaces by moving equipment to allow for 6 feet of separation between lab techs.

- Designate one-way traffic to the extent possible to allow a 6-foot separation and avoid people passing each other in tight quarters.

- Remove chairs and/or tables to achieve the 6-foot separation.

“With 25 percent occupancy, you can spread the workstations enough to be up to 6 feet apart and have only one person per aisle,” says Pravinata. “At 50 percent occupancy, two people will be in each aisle. Clear acrylic physical barriers may be necessary, where two people are working face to face. Materials for the barriers will have to be easily cleanable and possibly heat and chemical resistant.”

Harvard is attempting to take the CDC guidelines a step further by stipulating that “labs should try to achieve a distance of 9 feet or greater between workstations where feasible.” Any work that necessitates working in closer proximity than 6 feet requires preapproval, which will be granted rarely.

In addition, the university’s plan states that, “Whenever possible, researchers should be assigned a particular workstation. For shared workstations, only one researcher should work at a given workstation at a time, with disinfection of equipment and surfaces between users.”

Working in Shifts

One way to increase space utilization with these lower occupancies is for researchers to work in shifts.

“Fixed shift teams limit the size of any given person’s potential interactions over time and serve as a buffering function that distance alone does not accomplish,” according to the Harvard plan. “Fixing shift teams—at least in the earliest phase of reopening—functionally limits the number of people in the lab who would potentially be at risk for infection as well as the number who may need to be quarantined should a lab cluster emerge.” The need for the shifts to remain fixed “will necessarily change how projects are structured. Implementing shift work may necessitate more team science and if prolonged, could durably alter how we conduct research.”

Shifts can be arranged in multiple ways:

- Divide the work day into a daytime and a nighttime shift.

- Divide the week, such that researchers are working on alternating days.

- Create longer “shifts” that alternate blocks of days worked on campus with blocks worked remotely.

Lab time can also be arranged on a more ad hoc basis in coordination with the lab manager. Duke University offers this template for a shift schedule.

It is important that researchers not arrive early or stay late, so that the shifts don’t overlap, and that they build in time to wipe down all work surfaces upon arriving and before leaving.

Core Lab Challenges

The trend in research facilities design has been to increase shared equipment and core labs and animal facilities in order to increase space efficiency, save money on expensive instrumentation, and encourage interactions among researchers. Now, however, those shared spaces and animal facilities are presenting a particular challenge.

Researchers at the University of Chicago, for example, rely on technicians in the core labs to run samples for them and care for animals. Ramping up to 25 percent occupancy among researchers will necessitate at least 50 percent occupancy in the core labs, says Scott DeBlaze, executive director/assistant head of space planning, real estate management, and architectural services, at the University of Chicago Medical Center and Biological Sciences Division, Pritzker School of Medicine.

The university consulted with HERA Laboratory Planners to develop social distance recommendations, provide questions to ask their users, and share insights about what peers institutions were doing.

“Once we get to 50 percent researchers, we’re at 100 percent for the animal and shared research facility staff,” he says.

As of June 15, the University of Chicago achieved 25 percent occupancy for researchers, and is now contemplating how to adequately ramp up staffing in the core labs to accommodate 50 percent.

“We’re looking at what type of capacity we can work in, in specific designated areas,” he says. “We have designed signs explicitly identifying maximum occupancy in order to keep our staff safe and meet social distancing guidelines.”

Where researchers themselves need to access animal holding rooms and procedure room, they are being asked to schedule that time in advance to limit the number of people present. The University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) has created an online scheduling tool for that purpose, and is limiting occupancy in animal or procedure rooms to no more than two people from one lab at a time. “Research staff should follow room specific occupancy limit signs posted throughout the animal facilities.”

Protocols

Researchers are already accustomed to strict safety protocols in their labs, so they are well-positioned to adhere to additional procedural requirements.

The use of masks, for example, though widely accepted as an effective way to slow the spread of the virus, is being handled differently by each institution. Harvard requires that everyone on campus—in all buildings and even outside on campus—must wear a pre-approved surgical mask, except when eating. The University of Chicago, on the other hand, allows fabric masks, and they may be removed in single-occupancy offices. At Kansas State University, masks are recommended, but required only if occupants cannot maintain a 6-foot distance.

Institutions are also establishing health monitoring guidelines, and some are providing on-campus testing facilities.

“We are in the process of putting our own lab in place, to do COVID testing, supervised and run by the local hospital,” says Mary Jo Spector, AIA, director of Research Facilities Design, Construction and Maintenance at Florida State University. “We have asked all employees currently on site to get tested at the drive-through testing site.”

The facility, which will be able to process 5,000 tests a day and return results in 24 hours, will allow the university to do contact tracing.

Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) is limiting laboratory access to essential research personnel, and only “approved, critical vendors will be allowed on campus and in the labs. …PIs and center directors must keep a daily log (name, contact information) of all persons who have accessed the lab, including vendors.”

Pravinata and Harvey, working with engineers at Michaud Cooley Erickson, developed a list of adjustments to HVAC systems that may provide additional protection. They suggest that engineers review the following recommendations on a case-by-case basis, as most research environments have equipment and processes that are sensitive to temperature, humidity, and/or particulate levels:

- Provide more fresh air by increasing the air change rate. This will impact the pressure level in a laboratory and should be carefully considered in conjunction with the pressure of the neighboring spaces.

- Increase the humidity level. Some airborne viruses lose effectiveness above a certain humidity level. This modification may impact research processes and should be carefully considered.

- Install filters with a high MERV (Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value) rating. The higher the MERV rating, the more particles will be removed from the air. This adjustment may require more powerful fans to overcome the air pressure drops. This will need to be carefully reviewed by a mechanical engineer.

- Utilize UV lights inside of air handling units to destroy surface and airborne microorganisms within the air handling unit. This helps to ensure that the air leaving the unit is clean. There is almost no additional pressure drop associated with these systems, so they can usually be installed without other major equipment modifications.

- Treat the air and surfaces within the lab space by installing bipolar ionization systems in air handling units. These systems introduce ions into the air that are delivered to the space. These ions have been shown to neutralize many types of bacteria and viruses both in the air and on surfaces within the space. Like UV lights, there should be no additional pressure drop to overcome

Florida State University is replacing all air filters with MERV 13 where there is recirculating air.

Looking Ahead

Complying with new CDC guidelines and responding to ever-changing information about COVID-19 has caused lab facilities managers and researchers to rethink every aspect of how they do business.

“For so long, we thought about how do we become more dense and be more productive in less square footage,” says DeBlaze. “We’ve almost flipped that on its head.

“We have very dense floor plans and dense buildings for a purpose,” he says. “Now we’re literally saying, ‘Let’s get very few people in this space.’ How do we move forward with research and complete our government commitments and fulfill our grants?”

Those answers are particularly difficult in research that requires human subjects.

At the University of Illinois Chicago, “The Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research is now evaluating strategies to reactivate our human subjects research portfolio. Currently, ongoing human subjects studies remain limited to clinical trials with drugs or interventional strategies that are part of ongoing clinical care delivery, and those studies that can be performed remotely.” The university anticipates restarting volunteer human subject research in July with protocols that are currently in the works.

Researchers have also been cautioned to prepare for future shutdowns.

According to WPI, their “Research Lab Reopening Guidance lays out standards and factors based on the very real possibility that we may need to ramp down or shut down research again at any point due to COVID-19 concerns. Be prepared to shut down or rapidly ramp down research in on-campus labs on short notice.”

“Probably a third of the PIs (at FSU) have come back to some level of research as of June 1,” says FSU’s Spector, “but there is concern about starting animal research that can last from a few weeks to a number of years. They are worried about research being interrupted by another shutdown, without assurance that they were going to be allowed to continue.”

By Lisa Wesel