Northwestern University is continually working to grow and improve the quality of its research space inventory. A 2017 renovation and expansion of the Seeley G. Mudd Science and Engineering Library—situated in a prime location on the Evanston, Ill., campus—transformed a non-science building into a focal point of the university’s science complex. A desire to maximize research space within the constrained site resulted in a unique solution that leveraged both horizontal and vertical expansion.

Drivers for the Mudd expansion included the need for additional space to enhance the university’s research programs, a lack of other suitable locations on campus, an aging infrastructure, and the need for tighter temperature and humidity control for laser labs throughout the campus.

“We honed in on this 1970s Mudd building that sits in the middle of our science complex,” says Noel Davis, assistant director of planning and facilities at Northwestern. “Our vice president for research, Jay Walsh, has a philosophy that a research facility should be more than a building with only labs and offices. It needs to support the research ecosystem, which regards our principal investigators as entrepreneurs who need labs and offices and also soft spaces that any entrepreneurial or startup company would need to be successful.”

With this project, which began in late 2015, Northwestern repurposed an older building to advance its campus planning strategy to: recruit top faculty by providing innovative, well-equipped lab facilities for all researchers, particularly those with highly specialized needs; accommodate current and future research needs with space to grow; support research collaboration with spaces for social interaction and connections to the broader university community; engage students with hands-on learning and involvement in research programs to develop future talent; and locate computational support resources in proximity to the labs.

“The renovated building provides much-needed student study space, which isn’t abundant in our science complex,” says Davis. “It has allowed our laser lab researchers to expand into space that is appropriately sized and specified for their needs. It also has allowed our computer science program to accommodate an aggressive growth strategy for its CS+X initiative, which discovers and supports transformational relationships between computer science and other disciplines.”

The Mudd Makeover

Mudd Hall was a three-story library housing more than 300,000 bound volumes, but with no exterior entry at grade level. The only way to access the library was through connections with adjacent buildings.

“We essentially have what was once our least accessible building on campus now being the de facto front door of our science complex,” says Davis. “The original building sat about 36 inches above the ground plane, so there was no practical place to put an entry. This was something we set as a major priority to remedy.”

Zoning regulations allow the university to build up to 85 feet high, so a decision was made to not only increase the footprint horizontally, but also to embark on a major vertical expansion by adding two stories. The existing building was stripped of everything but its structure, which was reinforced by strengthening selected columns and adding shear walls. Then, a completely new building was constructed within, around, and on top of the original structure, ensuring adherence to current codes; leveraging the site for its highest and best use; creating a new façade; and installing new mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems.

The building, which is slab on grade with no basement, was expanded to the north, northeast, and east on each of the three existing floors. The original floorplate was 20,000 gsf per floor, which was increased to approximately 36,000 gsf. The total horizontal expansion was 50,000 gsf, while the vertical extension was 70,000 gsf.

“The existing footprint of the building was not large enough to do even half of what we had hoped to do,” says Davis. “We drew the perimeter of the maximum buildable areas of the site and then decided we would build all of that, so that became the building’s footprint. We opted to add two stories to the top of the structure to fully maximize the buildable envelope so we could accommodate the most labs, the library functions, and the research support entities.”

The Mudd project is not the first vertical expansion on the Northwestern campus. Kresge-Crowe Hall and the Technological Institute in Evanston have received additional floors in recent years, and the Simpson Querrey Biomedical Research Center in Chicago is designed with the capacity for a significant vertical expansion. Other facilities, like Mudd, were never intended to be expanded upward, but fortunately the foundations did not require significant modification. Davis points out that column reinforcement has been a necessity in the Mudd project and others to meet new seismic codes.

The original concrete Mudd building featured substantial floor-loading capacity, which eliminated the need to reinforce the slab. The vibration characteristics in the existing portions of the building are good, but they are even better in the new sections.

Floor by Floor Design Elements

The building is zoned by function rather than department, a design element that provides future flexibility for the lab space by accommodating a broader population of potential researchers from different departments, according to Davis. It also ensures the infrastructure capabilities of the space will be aligned with the users’ needs and fully utilized.

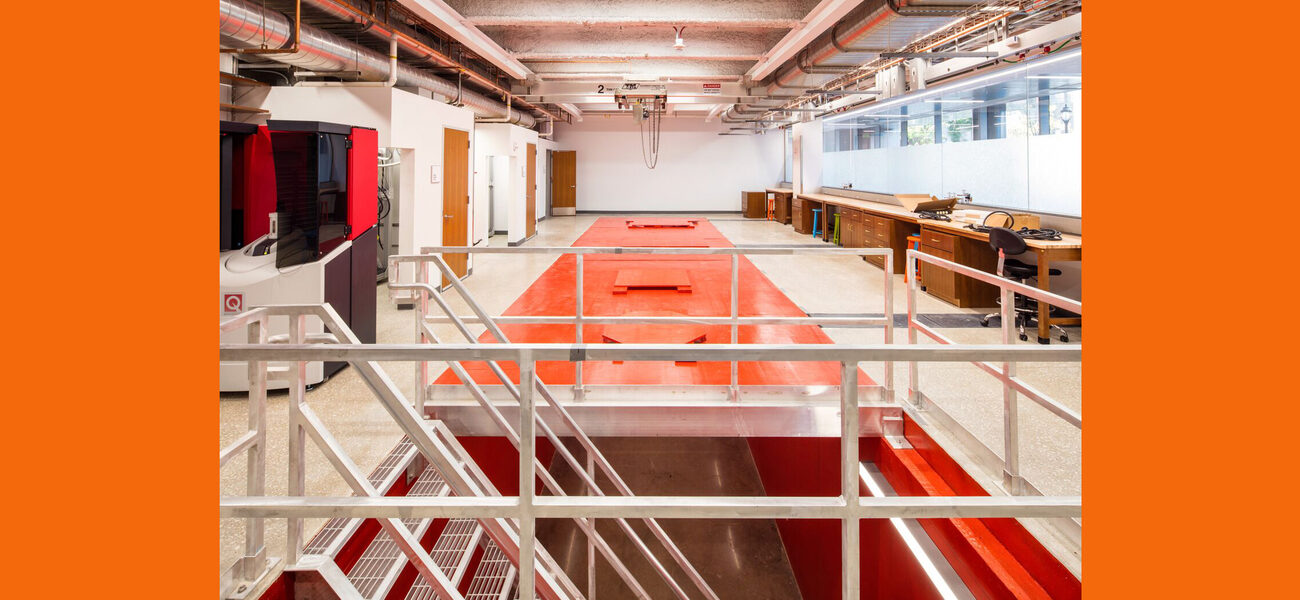

The first three stories have a 12-foot, 8-inch floor-to-floor height, and the new floors are 16 feet. The ground floor, which has a 35,000-gsf floorplate, is ideal for vibration-sensitive labs, and features two new pits for physics research with a third pit under construction. The pits—one of which is 45 feet long, 10 feet deep, and 10 feet wide—are used for sensitive experiments where electromagnetic interference, vibration, temperature, humidity, and other environmental factors must be tightly controlled. Aluminum, rather than steel, was used as much as possible on the ground floor to minimize magnetic field disruptions.

“By conducting these experiments in a pit, below grade, they are shielded from these interferences by the earth around them,” says Davis. “They have been custom built for each of three physics researchers to meet their specific requirements.”

The first floor includes individual, dedicated air handling units for each laser table setup; separate public and secure private circulation; student researcher offices within the secure lab suites; and a secure corridor that acts as a vestibule for the laser labs.

The second floor, which maintains its library function and is the most public, is accessible from the main ground floor entry, as well as a bridge to the adjacent Tech Institute. The bound collections have been reduced to 35,000 volumes, and there are many areas for collaboration, study, maker space, and classrooms. Highlights include active learning classrooms, 12 private study rooms that can be reserved by students or faculty, academic and research technology offices, and computer support resources.

One result of maximizing the buildable area of the site is that Mudd Hall has a 200-by-200-foot floorplate, which made it difficult to draw daylight to the interior. On the library floor, for example, islands of secure space are located in the center of the floorplate with the perimeter of the floor being dedicated to open study space. Transparent partitions provide a view to the exterior in almost every location of the library floor.

“Such a deep floorplate makes it difficult to get natural light into the center of the floor, which is far from the exterior windows,” says Davis. “We addressed this by locating laser labs, which require controlled lighting conditions, in the interior of the floors, and by maximizing open areas at the perimeter to allow natural light and views to penetrate deeper into the building.”

The third floor is dedicated to the Computer Science Department, which is ideal because it collocates all existing departmental faculty, student researchers, dry lab space, and 10 new interdisciplinary faculty on the same floor. It provides significant collaboration space and is a semi-private floor with one connection to the adjacent Cook Hall.

“Our computer science group is by nature very cellular. To foster collaboration, we ended up with a strategy where we used the corridors as streets to divide neighborhoods of offices and dry labs in the interior of the floor. We used the intersections of these corridor streets to create collaborative spaces and views to the exterior.” Glass partitions make the space feel more transparent, and overhead doors can open in five locations to connect the offices spaces to the corridor.

The fourth and fifth floors are designed as lab shell space to ensure the building is adaptable for future needs. University leaders envision three types of labs being housed on these levels: fume hood-intensive chemistry and life science labs, equipment-intensive materials science labs, and laser labs that do not require the high level of vibration sensitivity found on the ground floor.

The upper floors capitalize on the new 16-foot height for exhaust-intensive labs and have the capacity for 80 fume hoods per floor. These floors are not occupied, but Davis says future occupants may represent a cross section of both pure science and engineering disciplines focusing on materials science, life sciences, chemistry, and physics. The floors are zoned to have faculty and graduate student offices as well as several lab blocks along the perimeter with additional labs in the interior spaces.

The fifth floor features a large mechanical room to serve the third, fourth, and fifth floors and support future HVAC system needs. The mechanical equipment to serve the fourth and fifth floors has not been specified or installed, providing the necessary flexibility to accommodate a wide range of functions that may eventually be housed there.

By Tracy Carbasho