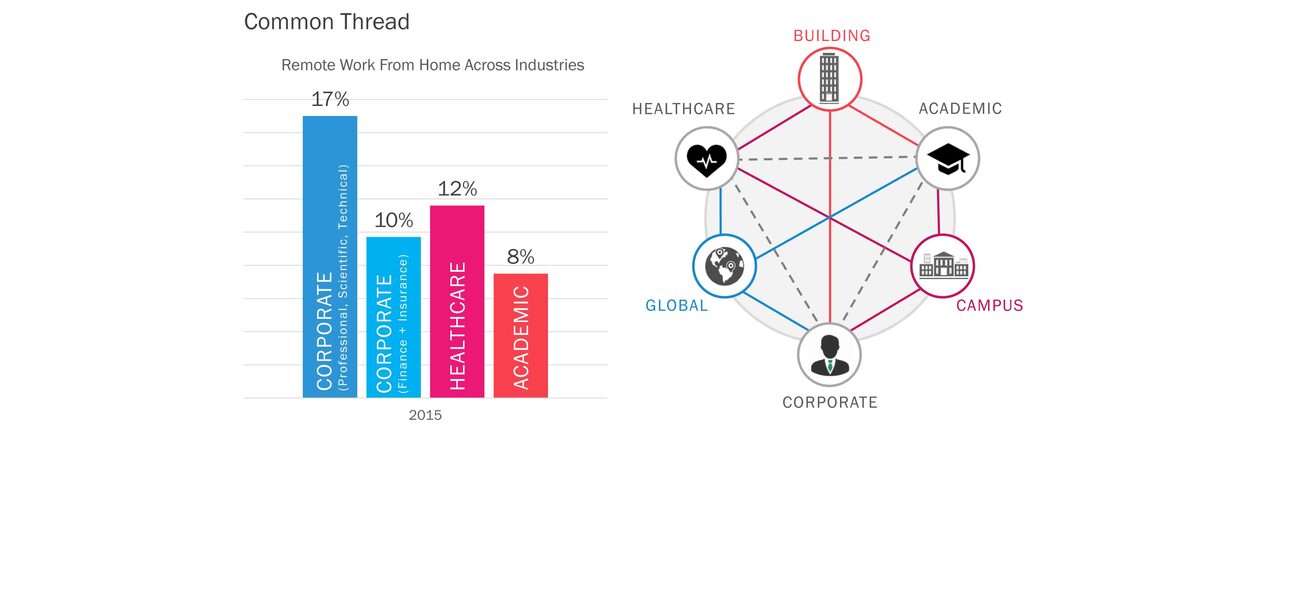

More and more, workers aren’t going to an office and sitting at the same desk Monday through Friday. Today’s architects, builders, institutions, and designers need to plan for a future in which workers are nomads—moving from one place to another within a building or campus, or showing up in the office just one or two days a week. These nomadic workers are often mobile by choice, taking advantage of the flexibility that technology has enabled for academic staff, knowledge workers, and even healthcare employees.

“The number of nomadic workers is rising immensely, and it is all due to changing worker preferences,” explains Keith Mock, a principal at the Ballinger architectural firm. “They are, in essence, transforming the concept of the primary workplace.”

Mock cites a Gallup poll from 2016 that found 43 percent of American workers were working remotely at least some of the time. The number will of course be limited by practicality—some jobs are not suited to remote work—but the poll notes a distinct increase both in the numbers of remote workers and the percentage of time they spend working remotely.

The Ballinger team identifies three types of remote workers: digital nomads, who can do their jobs from anywhere; campus nomads, who may work in remote locations in a large academic or corporate facility; and building nomads, who stay in a single building, perhaps using teaching space and research space, as well as a desk.

What does this mean for people who design workspaces in sectors where remote work is growing? Mock and colleagues Christina Grimes, Katherine Ahrens, and Kate Lyons have been exploring that question with a view toward bringing more flexibility to new and renovated offices.

Bringing Care to Communities

In healthcare, says Grimes, recent trends have moved toward more, smaller locations for care providers, rather than centralizing care in one large institution. “An institution may have five or six or 12 different sites,” explains Grimes. “That’s creating the continued push for the nomadic clinician.”

People who in the past may have merited a private office for status reasons—doctors, for example—are increasingly moving around during the work week. Grimes worked on a project for an ambulatory care center for PennMedicine, where administrators set the shared office requirement at 80 percent consistent attendance at the location. They wanted smarter, more flexible workspace solutions that got more patient care space out of the new building footprint.

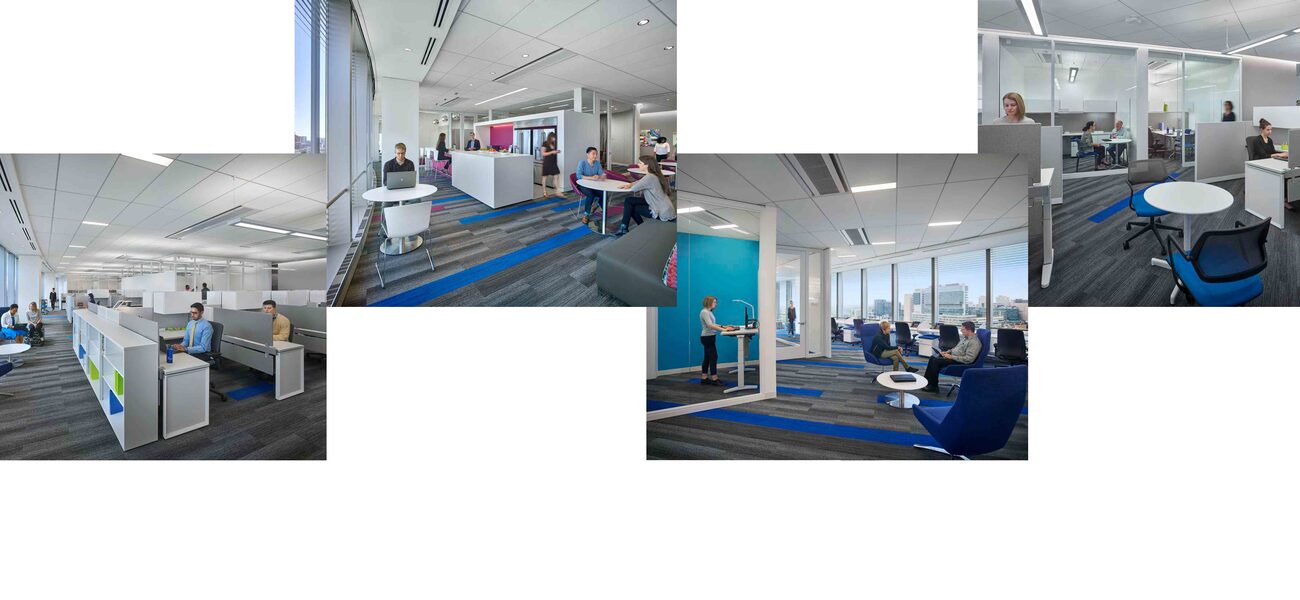

Ahrens worked on a project for a medical research unit at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where administrators found that existing office spaces were 40 to 60 percent vacant during the workday. They wanted smarter, more flexible solutions that got more out of the existing space. The resulting floor plan was implemented after a year of workplace strategy and change management aimed at encouraging the research teams to adopt more collaborative styles. The new space put collaboration seats nearest the windows, to further encourage contact and communication, with small breakout tables near individual desks for impromptu meetings.

All told, the new space offers 1.5 “alternate” workspace seats—conference areas, privacy rooms, café seats, collaborative semi-private spaces—for every traditional desk. The goal is to break down silos between teams and functions, encourage collaboration, and get more use out of the available room. Seventy percent of the seating is unassigned.

Grimes also worked on offsite workspaces for clinicians, including clinic spaces. A few different factors affected this work:

- The advent of electronic health records, mandated in 2014, shrunk the space needed for storage of paper charts.

- The hospital decided to ban private offices, making shared office spaces available only to those clinicians who are on a given site more than 60 percent of the work week.

- At the same time, medical standards changed to make private rooms a best practice for patient care, creating pressure to devote less space to administration.

“We started to look at how we could limit the enclosed assigned spaces and get to more alternative unassigned work seats to handle this ebb and flow of clinicians within the space,” says Grimes. With the transition to a hoteling office environment, where staffers reserve desks for the time they need them, one location was able to triple the number of spaces available for patient care.

While many workers seek nomadic and flexible situations, doctors often struggle to adapt to hoteling and unassigned seating. “All of those things become really big challenges to get the community of physicians to believe that this system will work for them,” explains Grimes.

The design also needed to be sensitive to patient privacy concerns and HIPAA requirements, and Grimes says it was helpful to have the hospital’s chief HIPAA expert on the leadership group for the project. In some cases they were able to use glass to preserve light and openness while protecting private conversations.

Campus Migrations

At the University of Delaware, the Ballinger team worked on a project to reunite the College of Health Sciences, which had been inhabiting two spaces. “The idea is that they would have all of their workplace and all of their program within this one building, and they could be nomads within this one structure,” explains Kate Lyons, who worked on the team but has since moved on to a role with Johnson & Johnson.

The university wasn’t quite ready to move to unassigned seating. “We’re trying to help them think differently,” says Ahrens, who continues to work on academic spaces for Ballinger. “The academic mindset is a little more traditional.”

Lyons explains, “We wanted to respect this culture, but we also wanted to plan the flexibility for the future and know that, as they are, everyone is becoming mobile. We might move in this direction.” The result was a space that prioritized research over ordinary workspace, using consistent neighborhoods while providing variety and choice to faculty and administrators who were only at their desks 45 percent of their work time.

Leaders had requested 60,000 sf of workspace, but the new facility was only going to be 50,000 sf. Since nearly two-thirds of that was workspace, it was easy to identify that space as a target for cuts. “We reduced the size of the new proposed spaces, but we still maintained our 249 work seats and in a variety of open and enclosed settings. This gave back the 10,000 sf just like that, and at $100 per sf fit-out cost, we were able to save a million dollars,” explains Lyons.

The designers reduced the size of a standard office significantly, but offered options for furniture that would cater to different workstyles. Again, open areas near windows and café seats were allocated to collaborative alternative seating, with private spaces for focused work and phone calls on the interior. A “communication crossroads” layout provided a visual identity that was similar on each floor.

For the 249 employees assigned to the space, the design made at least two seats available for each person, and left flexibility if the institution decides to increase headcount.

Effective, Efficient, Flexible

“This all comes down to, of course, real estate utilization and how we can optimize our real estate footprint to bring our costs down,” says Mock. Reducing the number of square feet per worker can yield big savings in real estate and operating costs, but at the same time open opportunities for spaces that encourage effective collaboration. By combining techniques and data from different work sectors, designers can craft design solutions for a given client or situation, while using metric-based planning standards to create predictable cost outcomes.

Mock notes that remote work is going to keep rising. Pieter Levels, a Dutch expert on remote work, estimates there will be 1 billion digital nomads worldwide by 2035. Some employers and institutions remain skeptical, or are unable to update their technologies as fast as the changing workforce might prefer.

“That is going to happen over time,” says Mock. “For instance, a grant-funded research center where they have already purchased their technology within the grant limits will have to wait for the next funding cycle.”

He and his team emphasize that change management is necessary to help organizations succeed in using new spaces effectively. A top-down directive helps, but it’s also important to be transparent and communicate effectively to connect the changing workplace to the goals of the organization

One point Mock likes to make in the change-management process is that this transition is already happening. “We always want to have space occupants take a survey; they say, ‘Oh, I’m in the office four or five days a week.’ Then when you analyze badge-swipe data, you realize they are only in two to four days a week. There is always that difference. It is fun showing occupants those charts. You do it in a very friendly, fun way.”

The result, he says, has been positive. “After they get used to working in a different work environment, they actually realize how much they enjoy a more open, collaborative space.”

By Patricia Washburn

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

Architect

|