Specialized biomedical core facilities accelerate scientific research and make the most of funding resources, but it takes considerable expertise in both technology and business to attain these results. To ensure the centralized model provides the most productive and cost-effective support to researchers, University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto has assembled a toolkit of proven strategies and operating principles. The foremost requirements are a robust knowledge base in science and technology and a strong business orientation.

“If there’s anything we have learned over the years, it is that if you don’t have management expertise in the core facility, it will not be successful,” says Ian McDermott, UHN’s senior director of research facility planning and safety.

Other success factors include the availability of training and education, open access, balancing revenue sources and expenses, and a realistic schedule of user fees supported by carefully documented utilization logs.

According to McDermott, research cores are defined as “centralized and shared resources that offer specialized instrumentation and/or services that are required by multiple investigators.”

UHN has extensive experience in core operations as Canada’s largest research hospital, with $344 million worth of research activity across a portfolio of four hospitals and five research institutes.

Six different biomedical cores serve its substantial scientific community. Each core is a discrete operating unit housing dedicated equipment in a dedicated space. The specialty areas are: genomics, advanced optical microscopy, spatio-temporal targeting and amplification of radiation response, flow cytometry, biospecimens, and biostatistics.

“These cross-platform cores account for nearly 70,000 sf of our combined total of 1 million sf dedicated to research,” says McDermott. “We are big enough that we have multiple different cores, in a scheme that avoids having independent cores with the same technology.”

Scientific and Management Expertise

While the technologies deployed throughout the UHN cores vary widely (from a spinning disc confocal microscope to a laser scanning cytometer, for example), one common characteristic is that the complex state-of-the-art instruments housed in these spaces demand considerable expertise to maximize their utility to researchers.

The need for expertise starts at the top, with core management.

“You must have scientific governance,” says McDermott. “Given the complexity of today’s equipment, it is absolutely essential for the core to be led by a scientist who understands where new directions in research, technology, and services are heading. You can’t just hire a general lab manager and say, ‘Please run this facility.’

“There is no written job description for the position,” he continues. “Typically in a core, the manager is someone with a lot of technical expertise who has decided not to pursue his own research agenda.”

However, the simultaneous need for management expertise creates a challenge, as the combination of science and business skill sets is rarely found in a single individual. UHN’s solution has been a hybrid approach to the core management structure. While there is not enough demand to assign an administrator to each core, an individual with the requisite business expertise can be responsible for multiple cores. McDermott’s group sometimes steps in as an additional resource.

“We have to be very cognizant that the individuals who do not have these capabilities need to receive support,” he says. “That’s where my role comes in, helping the cores set up as a business, instructing them how to deal with HR, facility, and financial management issues. Right now UHN helps to provide that support, but it is not clear cut across the board. This is something we are sorting through.”

Training and Open Access

The need for technical expertise extends beyond the management level. Core facilities are full of complex, high-tech devices, and it’s simply not feasible for researchers to understand all their capabilities and know how to operate each one without help. A staff of dedicated personnel is imperative, not only to provide operational assistance but also the raft of ancillary services — from advice on the various methodologies available to the analysis of the reams of data generated — that are integral to the core function.

"We need the expertise in the facility, because the technology is so challenging today,” says McDermott. “It is unwise to assume you can set up a core facility without someone there to provide training and education.”

Open access, albeit controlled, is another prerequisite for successful core management. While secured, the dedicated space is open to all those with a need to work with the equipment, whether within UNH or from external partnering institutions.

The Expense/Revenue Balance

Over the last 10 years, UHN has spent $57 million on its core facilities — more than $24 million for space renovations and almost $33 million in capital equipment. These expenditures were financed predominantly by grants.

“Those grant submissions were successful because we could show that the core approach is the right way to do things,” says McDermott, who lists several factors that make the centralized cores attractive to granting agencies as well as donors: the high rate of utilization and expertise available; the most time-effective use of equipment, for better return on investment; relieving individual researchers of the responsibility for expensive maintenance and service; gaining access to new technologies from suppliers at reduced prices or even at no cost; and lowering costs per sample.

Despite UHN’s success in obtaining grants for equipment and construction, there is no similar source to finance core operations.

“No granting agency in Canada is funding core facility management,” says McDermott. This has prompted UHN to develop other revenue streams.

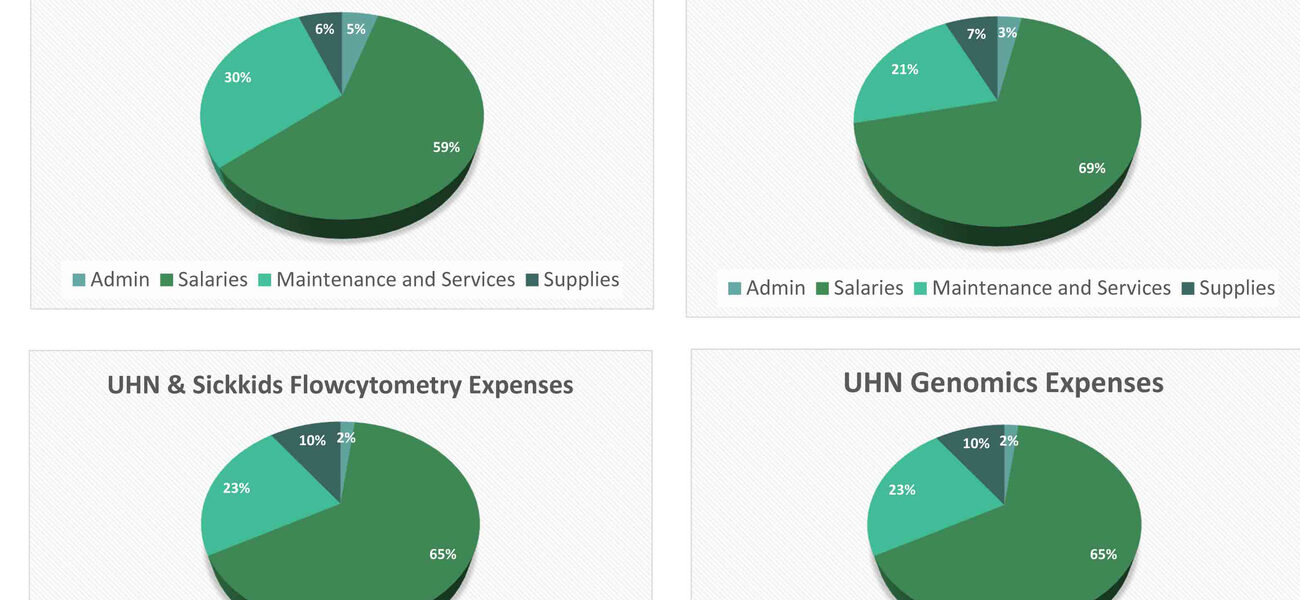

Following a model from the Canadian Microscopy Association (CMA), UHN has segmented core operating costs into four categories: salaries, maintenance and services, administration, and supplies. Data from three of its cores — microscopy, a flowcytometry partnership facility, and the genomics center — reveal that UHN’s costs across these categories are roughly parallel to the CMA benchmarks, which show that salaries and maintenance and services account for about 90 percent of total operating expenses.

The specific CMA numbers are: salaries, 59 percent; maintenance and services, 30 percent; supplies, 6 percent; and administration, 5 percent. The corresponding totals from the three UHN cores are: salaries, 65 to 69 percent; and maintenance and services, 21 to 30 percent. Administration and supplies combined account for 10 to 12 percent.

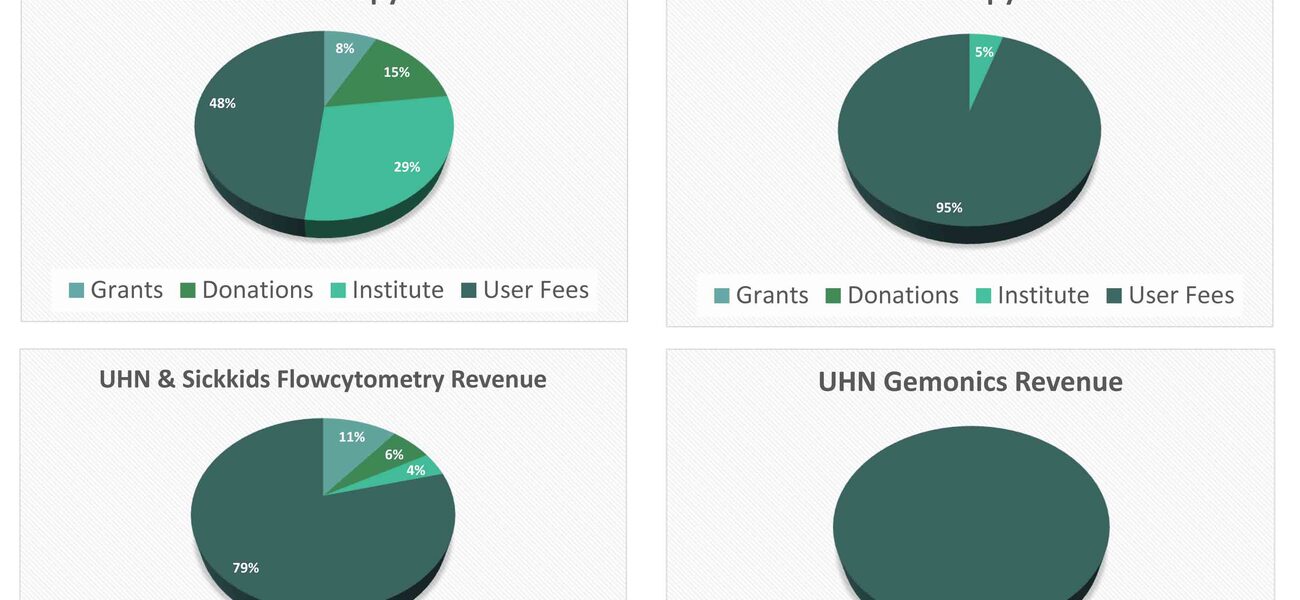

When it comes to revenue, however, the ratios at the two organizations diverge.

The four revenue streams are grants, donations, institute, and user fees. The CMA revenue distribution breaks down into 48 percent from user fees, 29 percent from the institute, 15 percent from donations, and 8 percent from grants. At UHN, user fees account for a much higher portion of the total. For the microscopy core, 95 percent of revenue comes from user fees, with the remaining 5 percent from the institute. At the flow cytometry facility, the distribution is 79 percent user fees; 11 percent grants; 6 percent donations; and 4 percent institute. Revenue for UHN genomics comes 100 percent from user fees.

“Interestingly, the Canadian microscopy group as a whole is looking at just under 50 percent of revenue coming from user fees,” observes McDermott.

UHN’s large portfolio gives it a much broader user base than many other institutions, thus increasing the availability of potential user fees. But that is not the only reason for the difference between its own and the CMA numbers. Rather, it’s the result of a carefully designed business strategy.

“We set up the culture of the cores being self-supporting about five years ago,” says McDermott. “UHN simply does not have the funding to contribute 29 percent of core expenses. That would take away from our ability to hire scientists. So we have gone to a business model whereby user fees fund almost all of a core’s operating costs.”

User Fees and Utilization Tracking

UHN has a three-tier user fee schedule, depending on where the scientist comes from. The lowest level (for example, $29 per hour for a confocal microscope) is reserved for internal research teams. Charges for an external academic group are 20 to 30 percent higher. Private sector users can pay two to three times as much.

Service capacity is promoted through organizations such as the CMA, which disseminates information about all the technology available at UHN’s Advanced Optical Microscopy Facility; and Compute Canada, which spreads the word to those interested in high-performance computing.

Regardless of the user, researchers who want to work in a core must first book the desired piece of equipment. They are billed for the time scheduled, whether they use it or not, “because the technology needs to be available for others,” explains McDermott.

A meticulous way to track utilization is essential. Given its varied array of cores and equipment, UHN was not able to use commercially available, off-the-shelf software for this function. Instead, it developed customized tracking systems, which not only ensure accurate chargebacks to user groups but also document the role each core plays in an institute’s research programs.

“The only way to justify core expenses is by keeping detailed utilization logs,” he says. “Without the utilization data, we can’t go back to each of the five institutes we serve and show them how much their institute is using the core facility. This is essential in asking for their support.”

McDermott adds the caveat that the billing records have to be clear and easy to understand.

“If you are not open and transparent with your research community, you will not get the support for cores that you need,” he concludes.

By Nicole Zaro Stahl

This report is based on a presentation McDermott made at Tradeline’s Core Facilities 2015 conference.