Facility managers can achieve optimal performance by “sweating their assets”—making existing assets work harder—through a careful analysis of what factors contribute to the highest throughput and then undertaking initiatives that will help them reach those goals. Doing so may eliminate the need to create expensive new space but may require facility redesign, says Cyrus Yang, executive director of delivery system planning for Kaiser Permanente.

“What I mean by ‘assets’ is not just the physical plant,” he says. “Some of our best assets are people. It really is balancing resources to optimize an environment.”

Optimization can be achieved by utilizing capacity expansion “levers”—activities or initiatives that cause something else to happen, for example reaching a facility goal, such as expanding capacity or throughput.

“This process is a connective tissue between the highest level of capital planning (over a 10-year period, for example) and the level closest to the client,” notes Yang. “What this does is essentially prioritize process improvement work, so those people can come in and know how to get the highest value and best serve the organization.”

One of the most successful examples of this approach is the airline industry, he says. Rarely do flights have empty seats anymore. They refurbished existing fleets and initiated “levers” to fill more seats, such as adding more planes to existing routes, offering last-minute bargain fares, and overbooking flights.

The Little Clinic That Could

Six years ago, Kaiser Permanente, which owns or operates about 70 million sf of facilities, started an initiative that would grow its patient base without new construction. They looked at the throughput (face-to-face visits with a provider per exam room annually) of their 450 ambulatory facilities.

“We have thousands of exam rooms, so it was important for us to understand how we were actually performing. It was surprising to us,” says Yang.

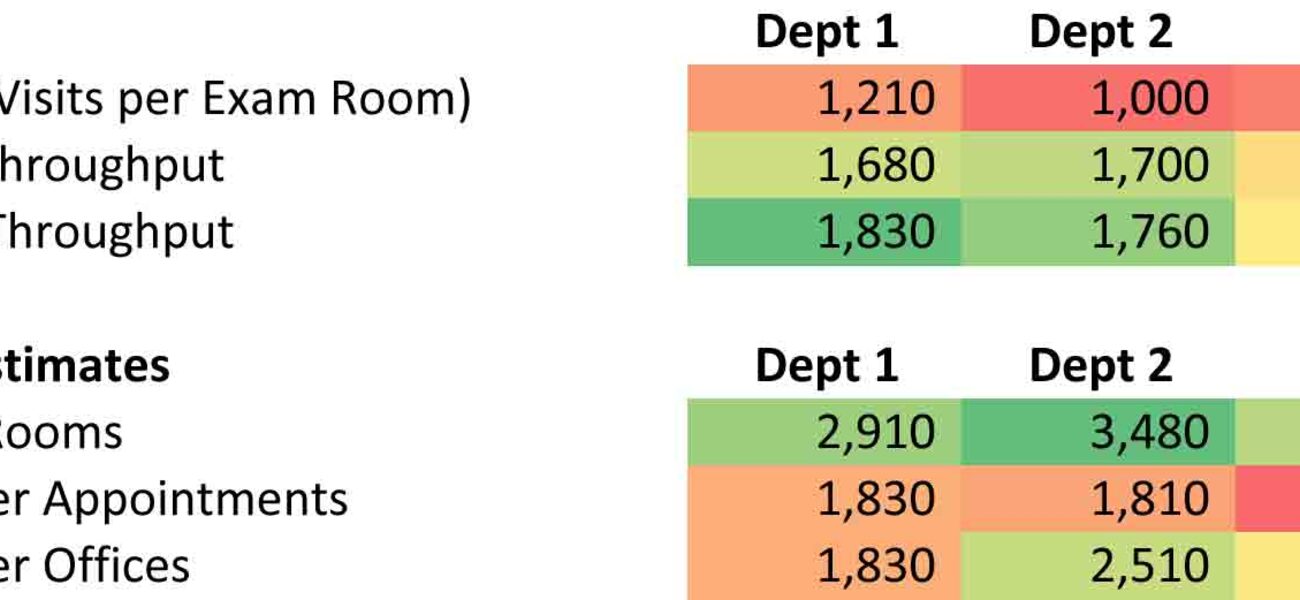

In California, the facilities were doing about 1,600 to 1,700 visits per exam room annually. In the remaining regions, the average was 1,000 to 1,200. Staff cited various reasons for the lower performance: older facilities, condition of facilities, poor layout and design, having to adapt to existing space, and small size (80 sf per exam room as opposed to the standard of 100 sf).

Then Kaiser Permanente discovered that a little clinic in Kona, Hawaii, had many of the same limitations yet was accommodating 1,600 to 1,800 exam room visits annually. The three-story building with six pods held 20 exam rooms and 12 provider offices, and was a hub for 25 rotating specialists. In some areas, up to four providers shared a single office.

“Compared to other regional facilities, it had the worst adjacency, the worst sizing, and had one of the worst facility condition index scores. It was incredibly complex,” says Yang. “To further complicate matters, rotating specialist doctors often had to fly to the island where Kona was located.

“So we had two questions: How was it achieving this throughput? And, can other clinics replicate the success of Kona?”

Measuring and Replicating Success

Kaiser Permanente’s team analyzed Kona's success and developed a way to replicate it using a four-staged approach that can be adopted by other industries:

- Measure current throughput and variance.

- Estimate potential capacity without any changes to facility operation.

- Identify, quantify, and prioritize ways to expand capacity.

- Pilot capacity expansion, and measure outcomes.

In measuring the throughput, they looked at not only the annual average, but also daily specifics, says Yang.

“When you look at just one number and see that the clinic ran at an average 1,300 visits per room, it doesn’t really tell you much. But if you ran as high as 1,600 or 1,700 on 20 days of the year, that tells you a little bit more.”

Kaiser Permanente looked at whether or not those 20 days were materially different than other days: Did they have fewer providers? Did they have fewer nurses? Was it an infrastructure issue? Were facilities under construction? What was going on?

In order to benchmark performance, it’s also important to look at the variation that occurs between single departments across facilities, adds Yang. If a region has multiple labs across several facilities, for example, all should be measured against one another, because unless they centrally run a tight ship, there will be insightful operational differences.

“Look at days and/or departments that run the hottest, and look at why those were fundamentally different—staffing, equipment, etc. You have to understand all factors when determining the optimal rate. You challenge people to remember those days, or run an experiment to replicate them by scheduling tighter than usual.”

After this initial analysis, estimate the potential capacity if no changes are made, he says.

“By looking at your potential capacity without changing anything, it is like saying my car is technically capable of going 100 miles an hour even though I only average 60 miles an hour. The question becomes, how do you increase the average to 80 or 90? You have to look at the different components that factor into potential capacity,” says Yang. “The ones we decided were the most important components were the exam rooms and the provider schedules.”

When undertaking the next step—identifying, quantifying, and prioritizing ways to expand capacity—it’s important to consider the main “rate limiters,” says Yang.

“For a healthcare organization, the number of exam rooms, or labs, or parking could be rate limiters. There are any number of different possibilities, including staffing,” he says. “But the idea is that you can only go as fast as your rate limiter. My car can go 100 miles an hour, but it could go 120 if I had a stronger engine and better suspension.”

The final step is to look at all the different ways to expand capacity. Depending on the facility, the management team may be looking at maximizing the supply side, the demand side, or both, notes Yang. Most importantly, identify a comprehensive set of “levers”—the activities or initiatives needed to reach goals, he adds.

For maximizing the supply side, the most obvious levers for Kaiser Permanente, and the typical “go-to” ones, are: adding new space, adding operating hours in a day, adding operating days per week, and increasing the number of full-time employees. “But, all those things cost money, and they are not cheap. There are a lot of operating expenses that usually overshadow the capital expense over time,” notes Yang.

Options with less financial impact could include: looking at “leveling” schedules; standardizing room design/supplies, so appointments take less time; creating an appointment schedule with similar visit types grouped together; and increasing appointments per provider.

“The next step is to sort them on a biggest-impact, easiest-to-implement chart. You can prioritize based upon cost, the operational difficulty to implement, the political difficulty to implement, etc. Every facility may have a different prioritized list of options.”

The fourth and final step is to pilot the capacity expansion and measure the outcomes. Start with some of the easier “levers” that have been identified and work backwards toward the most difficult, says Yang.

“Start pulling these levers and, ideally, the facility will move in the direction you would like it to move. Hopefully, you will see an improved throughput relatively soon, within three to six months, or whatever your timeframe is after implementation.”

Yang notes that it’s also important to be cognizant of “sweating your assets” too hard, at the expense of the people who work in the facility. Don’t underestimate the human capital element.

“In some cases, it may make sense to build more exam rooms rather than have physicians and associated staff be unproductive. Even more so for a lab, you want to sweat the assets that are most expensive. When you have higher fixed costs, sweating those fixed costs will get you more for your money.

“You also can stretch so hard that you shoot yourself in the foot. There’s a point at which you achieve the balance that optimizes the return on your investment. That point may be farther down the line, depending on a facility’s fixed versus variable costs.”

How Well it Worked

Kaiser Permanente found that even Kona was only pushing about half of the “levers” they established for improving capacity, so it could further improve by initiating some of the other activities the exercise had identified.

The four-step approach worked so well that Kaiser Permanente piloted it in other regions and is working to extend it across the enterprise. The approach now seems to be gaining a foothold in the culture, says Yang.

“People saw that it worked and started doing it on their own. Growing into built capacity is an important part of the affordability equation. If they’re not using the specific techniques we identified initially, they are coming up with their own homegrown levers.”

Yang’s group learned three lessons that are important to keep in mind for any facility implementing this process:

- Optimize operations first, and build second. “This is such an obvious thing, but we don’t always do it. You delay spending capital, and when you actually build, the facility is going to be operating smoothly and efficiently.”

- There are myriad operational levers to consider, many of which may require facility redesign. “Our architects have never been busier, because what this has done is introduce a whole new set of work. Now they have to work within the existing four walls and make improvements, so that form really does follow function.”

- Culture eats strategy and data for breakfast. “Without strong cultural headway or support from key stakeholders behind you, it would be difficult to do any of this work.”

“You can start creating culture from the bottom up. Start doing this as a pilot on a small basis, and success begets more success. You end up with an organization that knows how to do it and is driving performance excellence.”

By Taitia Shelow

This report is based on a presentation Yang gave at Tradeline’s 2014 Conference on Strategic Facilities Planning and Management.