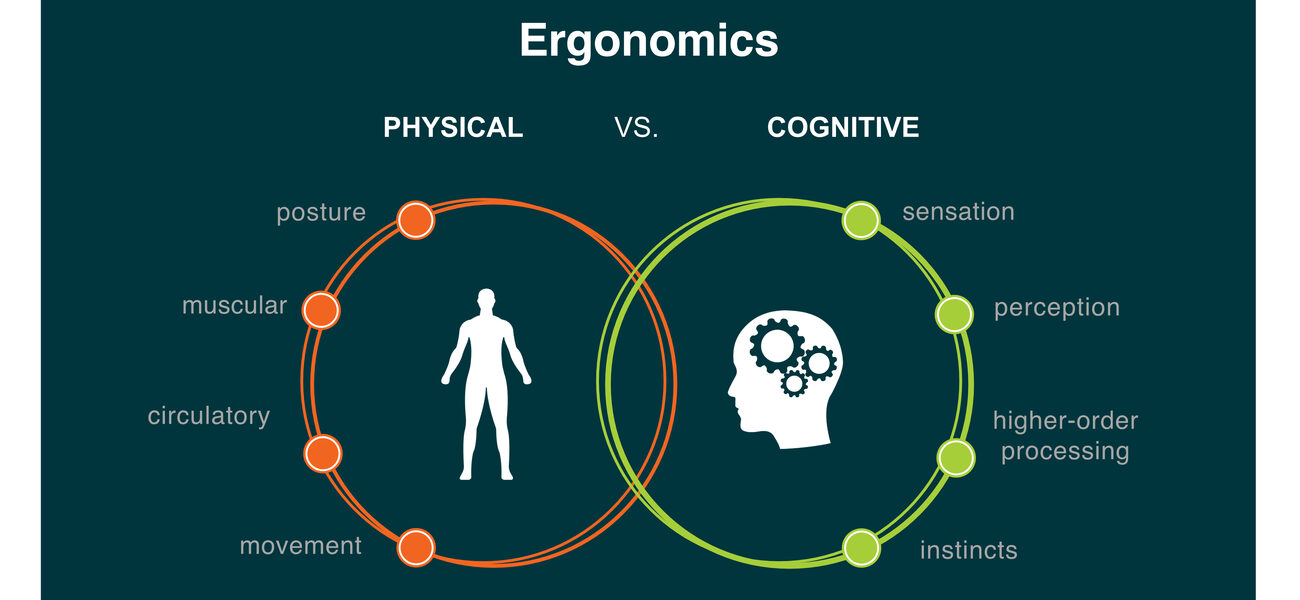

Creating a healthy and comfortable workplace is simply good business. Physical ergonomics—designing a workspace to accommodate the physical needs of the occupants—has long been accepted as a way to improve productivity and reduce workplace injuries. Increasingly, employers are turning their attention to cognitive ergonomics, which focuses on how a workspace impacts the occupants’ ability to think. Improving elements such as air quality, temperature, lighting, and noise can increase cognitive performance by as much as 50 percent.

“Cognitive ergonomics looks at cognitive processes in work settings to optimize human wellbeing and systems performance,” explains Kelly Bacon, global practice lead for AECOM’s People + Places Advisory practice. “We are talking about neurological performance, emotional performance, and physical performance, because they are connected.”

“We spend up to 90 percent of our time indoors, so 90 percent of our life we are subjected to external factors that can affect our productivity and our performance," adds Oriana Merlo, practice lead for AECOM’s People + Places Advisory practice.

Counting the Ways

A whole range of factors in a workplace can compromise its cognitive ergonomics.

Water quality: Water pollutants can lead to dehydration, nausea, and other gastrointestinal issues, not to mention more serious side effects, such as cancer, leukemia, and stroke, according to Merlo. And a study published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health found that exposure to higher levels of aluminum in drinking water was associated with lower cognitive function in adults.

Merlo recommends testing water quality quarterly using a regulated laboratory, not a do-it-yourself kit whose results can vary wildly, and to check water in ice makers, coffee machines, drinking water dispensers, and kitchen faucets.

Air quality: Keep an eye out for yawning, as it may be a symptom of bad air, particularly in populated spaces such as meeting and conference rooms. Yawning might also indicate that the space is overcrowded, or that the ventilation system can’t keep up.

“Carbon dioxide gives you brain fog,” says Merlo. “It creates a drowsiness, a dizziness; your cognitive performance, your ability to think and act clearly, is impaired because you’re breathing less and less oxygen.”

A 2012 study showed that people working in environments with low ventilation and increased levels of indoor air pollutants experienced cognitive performance reductions of 50 percent compared to those in well-ventilated spaces.

In AECOM’s study of National Grid, a multinational energy company, researchers found that in seven different locations, employees working in newer spaces with better air flows had 8 percent higher cognitive performance, says Bacon. AECOM found similar improvements at Estee Lauder, the beauty company, and at AECOM itself.

Merlo recommends improving ventilation rates before a room becomes crowded, and tying the HVAC system to room booking systems to prepare rooms before meetings start. High ceilings won’t help, because carbon dioxide is heavier than oxygen and sinks to the ground.

She recommends installing an internal air quality (IAQ) monitoring system that monitors both coarse and finer-grained particles. Look for volatile organic compounds, as well as ozone and carbon dioxide, and test a variety of places in the building.

Humidity: Moisture in the air can cause problems both when it’s too high and too low.

“At the low level, we’re providing an environment where viruses breed, especially in the wintertime when it’s colder and less humid,” says Merlo. “We’re inviting things like flu virus and coronavirus to breed and stay in the air longer.”

But air that is too humid can breed fungal spores and mold, and allow them to linger in the air longer. People can then breathe them in and absorb them through their skin.

Higher quality IAQ monitors typically include a hydrometer that measures humidity; the ideal relative humidity is between 40 and 60 percent.

Seating: In addition to causing carpal tunnel syndrome, joint pain, and headaches, sitting the wrong way in the wrong chair can decrease your mental sharpness. “If your body is in a cramped position, you could be impeding the blood flow to your brain, which means your brain is not getting enough oxygen,” says Merlo.

The best way to correct this issue is to provide ergonomic assessments and fully adjustable furniture, including desks, chairs, and fully articulated monitor arms, says Merlo

Wearable posture sensors can sync to your smart phone and alert you whenever you slouch.

Light: As with humidity, too much or too little light can lead to discomfort, as can exposure to the wrong color of light.

“We have impaired cognitive functions when exposed to the wrong light,” says Merlo. “We can’t see clearly, we’re not thinking clearly, and our brain doesn’t know how to react.”

A 2017 study published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine showed that workers in offices with optimized daylight conditions performed 10-25 percent better on cognitive function tests than those in offices with poor lighting.

A spot meter can test the quality of light in a workspace. A lux meter will measure only incandescent and fluorescent light, whereas an LED meter can also measure blue light.

Bacon cautions that there’s no such thing as perfect lighting: Not only do needs vary by time of day, but one in five people is neurodiverse and may process external stimuli differently. Where possible, it’s a good idea to give people some control over their own light levels.

“There’s a much bigger discussion here about how having too much blue light interferes with our natural sleep cycles (circadian rhythms),” says Merlo.

Temperature: Only 11 percent of workers say their workplace is the right temperature, according to Bacon—if employees are too hot, they may lose focus; too cold, and they make more mistakes.

“You have decreased motor skills when it’s too cold because you’re too busy shivering, so you can’t do that fine-tuned stuff,” says Merlo. “Also, as it gets colder, you tend to get more mistrustful of others, so if you want to have a successful collaboration, don’t make the room too cold.

IAQ sensors can tell you which parts of your workspace are warm or cool, she says. “Give the real-time readings to the users so they can choose where they want to sit.”

Men and women have different optimal temperatures, which can make it difficult to accommodate both in the same space: Data show men are at their cognitive best at 68-69 degrees while women’s cognitive peak is from 70-72.

Noise: Street noise, coworkers’ conversations, the buzzing of a fan on a PC—all kinds of noises can trigger distractions and lower cognitive performance and problem-solving ability by 10-25 percent, according to a 2000 study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology. These distractions are expensive. The average knowledge worker loses 28 percent of every day to unwelcome interruptions, cutting U.S. productivity by at least $650 billion every year, says Bacon.

Nor is it true that younger workers are better at filtering out background noise, she says. “That is not even remotely true. Your ability to filter out sound is more dependent on your psychological profile than your gender, your age, or anything else.”

Here too, metering can help you assess the seriousness of the problem, then establish active and quiet zones. “This might seem obvious, but it doesn’t always happen,” says Suzanne Klein, education market leader for AECOM, focused on university projects.

Vibration: Vibration is often overlooked as an indoor environmental concern, but it can affect behavior. Whether you are sitting next to equipment, such as a high-velocity printer, or you’re in a building that creaks or flexes, vibrations can hurt productivity. “If you’re subjected to it over a period of time, you can start getting headaches, depression, and motion sickness,” says Merlo.

To understand occupants’ exposure to vibrations, conduct spot checks with a handheld meter, and work in conjunction with a structural engineer to better understand the source/cause of vibrations, recommends Merlo.

Making the Case

Even though most spaces have room for improvement, it’s not always easy to make the financial case to invest in those improvements.

First, point out that it will make your company work smarter.

Second, note that an uncomfortable office is a competitive disadvantage. “It’s not uncommon now to find workers who will change jobs because of the environment that they have to work in,” says Merlo.

Third, present evidence. Klein and Merlo recommend delving into the research conducted by the International WELL Building Institute, which developed a standard for creating interior spaces that promote occupant health and safety. They also point to the book "Healthy Buildings: How Indoor Spaces Drive Performance and Productivity," by Joseph G. Allen and John D. Macomber (Harvard 2020), which makes a strong financial case for improving building quality. Macomber’s research shows that a 1 percent investment in improved ventilation could increase productivity by 1.5 percent due to decreased absenteeism.

If the boss still doesn’t listen, maybe the landlord will. Improving indoor environmental quality is a good way to create real estate value, says Macomber: Healthy buildings command a 4 to 7.7 percent rental premium over non-healthy buildings.

Easily Attainable Improvements

A new HVAC system can be a significant expense, but there are other measures you can take that will enable you to improve your built environment faster and at a lower cost:

- Add some green. Human beings feel better around nature. Bringing in a plant or even a picture with some natural imagery can help keep the blood pressure down. “Having done a wellness project a few years ago, I realized how important it is in terms of impacting the nervous system, and how we can think about incorporating things to include nature, natural patterns, and plantings in the interior,” says Klein.

- Soften ambient noise. A white noise system can cover up distracting noises, but can also be expensive. An easier fix is to add acoustic panels to ceilings and walls, and opt for soft woven furnishings to absorb sound. It can also be helpful to bring in natural sounds: A small fountain that adds a sound of trickling water can be soothing, says Klein.

- Install task lamps. Being able to control their light source individually makes people more productive, and a good-quality LED task lamp with variable light levels and color temperatures can cost as little as $20. Better office lighting can improve sleep quality in as little as two weeks, says Merlo, particularly a lamp that allows you to change the color temperature—cooler in the morning, warmer later in the day.

“Our buildings have a direct impact on occupant health and emotional well-being,” says Bacon. “It’s not enough that they don’t make us sick—they can make us better.”

By Bennett Voyles