Creating an efficient, productive, and safe rodent vivarium of any size begins by determining the current and future needs of both the researchers and the animal care staff. Collecting data from users throughout the process of new construction or renovation ensures the design aligns with their research, equipment requirements, utility specifications, and animal care needs.

“We need to know how animal facilities work, because when investigators design for themselves, it may never work for the animal care staff,” says Michele Cunneen, president of Animal Research Consulting LLC in Natick, Mass. “The animal care staff, on the other hand, will design for themselves, and it may not work for the investigators.”

The type of research dictates design elements, including the size of various spaces, the building materials, the level of containment, safety precautions for the building occupants, and animal care.

“The research models are really important, because some research requires only 2 feet of bench space,” says Cunneen. “For example, if you’re doing a standard pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study and you need to take blood samples from a cage of mice, you don’t need much space. However, if you want to do a behavioral study, you might need more equipment, which would require a larger room.”

Cunneen obtains buy-in from clients by using basic “crayon” drawings, rather than detailed architectural depictions, to illustrate everything from design features to interior furnishings before finalizing a floorplan to make it easy for users to conceptualize the finished facility. Providing an abstract floorplan with all of the design features without the context of the full floor plate can prevent building occupants from getting attached to a specific layout that may change later due to construction issues.

Plan for Expansion with Multipurpose Rooms

Flexibility is important in continually changing research facilities that must accommodate future experiments with varying needs for animal housing and care, equipment, and services. Designing each space to facilitate two functions—either two current ones or a current and future one—helps plan for the requirements of future directions in research. The facility, its infrastructure, and furnishings should be designed so each space could be used for at least two purposes.

“A large animal holding room can easily become lab space,” says Cunneen. “If you’ve put all of the services in the ceiling, you roll out the animal racks and roll in modular benches and all of the biosafety cabinets you need. You have the electricity in the ceiling to run any of your tissue culture and anything else you need to plug in.”

Cunneen notes most flexible design features cost less than installing fixed systems. For instance, installing electrical services in the ceiling typically costs less than placing them in the walls, and the cost of movable lab benches is comparable to built-in, fixed cabinetry.

“Having rooms with multiple possible functions allows you to shrink total square footage, so the decrease in square footage will often pay for the double duty,” she explains. “As you move from rodents to larger animals, caging needs change significantly, but the infrastructure and procedure room concept of movable benches and multi-use rooms can still be incorporated.”

Design Highlights

Vivariums, especially rodent facilities, should be flexible enough to accommodate many current and future types of research; provide space that can be used as a vivarium now, but serve another use later; be reconfigured with minimal disruption; offer maximum animal holding capacity; and have maximum seating and office space.

Spaces that serve multiple functions enhance efficiency and productivity. Large animal holding rooms can be used as lab space, while procedure rooms can serve current and future research needs. Abundant storage and a designated docking place for carts keeps hallways clear and frees space in rooms that already serve multiple functions.

Both labs and animal care spaces require central services, with sufficient plugs for freezers, ice makers, liquid nitrogen storage, dry ice, and pipe lab gas. Even if current research in a vivarium requires only carbon dioxide, pipe racks in the ceiling provide easy access to pipe other lab gases in the future.

“Installing the pipe rack with all possible lab gases in the ceiling adds increased costs during construction and installation, but it will minimize the time and disruption later if you have to switch from one gas to another,” says Cunneen. “An alternative would be to just install the empty pipe rack, and then you would at least have the space and a clear path to install pipes later.” Often, if you do not explicitly reserve space, some trade will use it for something else, which will complicate and increase the cost of future retrofits.

All other services—including the lights, HVAC system, and ventilated rack connections—also can be located in the ceiling. A bayonet gate allows ceiling access to adjust the airflow for the ventilated racks. Drop ceilings are common in rodent facilities, because ventilated cage racks typically connect directly to the exhaust air ducts, resulting in a more energy-efficient, drier room environment. The ceilings usually do not get wet in facilities that house rats and mice, although ABSL-2 and ABSL-3 facilities will require moisture-resistant ceilings that can be hosed down.

Care must be taken when selecting doors that not only meet the complex biosecurity specifications for a vivarium, but also make it easy to transport equipment in and out. Since many pieces of equipment are wider than a standard 36-inch door, Cunneen says a door with a minimum width of 42 inches is preferred at all locations in the facility. A wide hinged door, with a leaf and a built-in hold-open feature, also eliminates impediments to larger pieces of equipment if a facility is repurposed or retrofitted.

Design elements accessible to people with disabilities include height-adjustable biosafety cabinets and automatic doors that are easy to open.

Flexible design features begin with hallway corridors that are 5 feet wide, or 6 feet if a facility does not have a designated place to store carts. Double swing or leafed doors that are at least 42 inches wide are ideal, especially if pallets of materials are routinely transported in and out of certain spaces.

Biosafety cabinets measuring 5 feet are more convenient than 4-foot ones because they can hold more supplies. Modular benches that do not attach to the wall and require only a twist lock for the power cord offer flexibility because they can easily be moved.

Flexibility and convenience also result from having emergency power in more than just the holding rooms.

“Emergency power is limited, and a generator can’t supply power for all of the work taking place in the facility,” says Cunneen. “I suggest putting circuits in every procedure room, so if the space is used as a lab later, you have the opportunity to plug in a critical piece of equipment 24/7.”

Other flexible design ideas include providing reverse osmosis water in several rooms where water bottles are used on cages. Glassware or commercial dishwashers are more cost-effective than installing a cagewasher, especially if disposable caging is used.

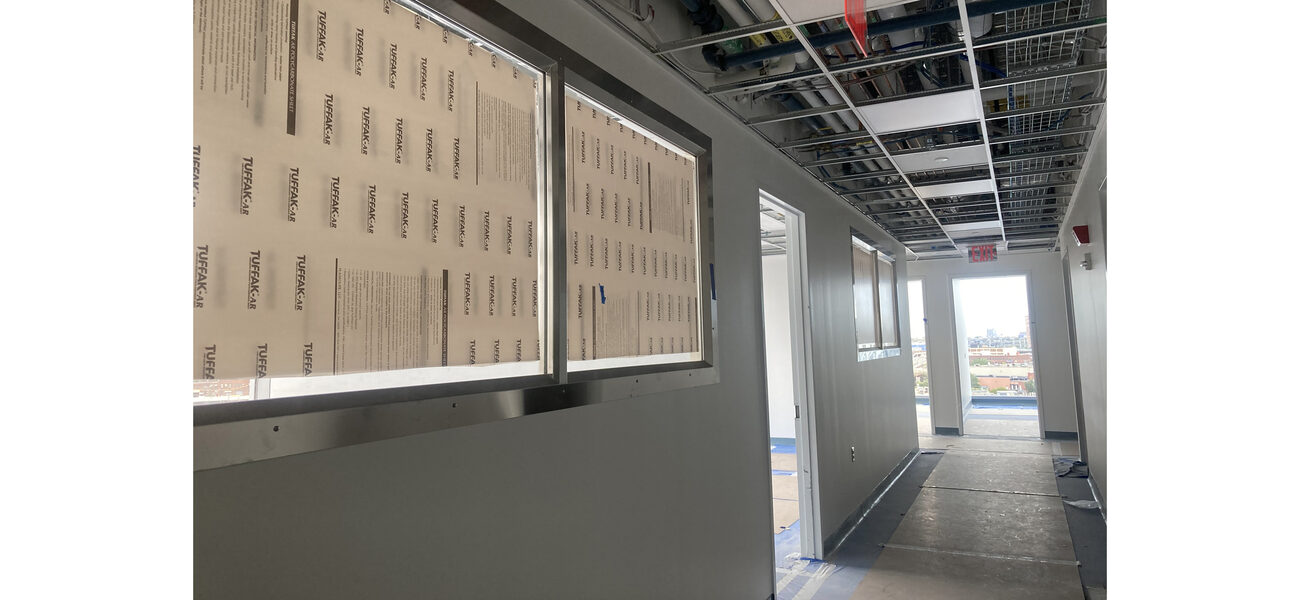

Because many employees work long hours, it is important to keep the work environment pleasant and bright in an animal care facility, with colorful floors and accent walls and as much natural light as possible through clerestory windows and glass doors.

Biosecurity and Intellectual Property Concerns

Disposable caging eliminates the need for autoclaves, cage washers, and multiple failure points during the maintenance of facilities that require a high level of biosecurity. The cages are pre-bedded, pre-watered, irradiated, sterile, and sealed until they are opened in a contained biosafety cabinet or a separate procedure room. Some disposable cage models can serve as a holding room with a completely isolated microenvironment via an independent double-HEPA filtered air supply.

Questions often arise about housing mice and rats of different health status in the same room with no separation. Cunneen notes the current trend in animal labs is to abide by the high health standard of using very clean immunocompromised rodents or those free of opportunistic viruses that could be transmitted to staff or other animals. However, much research still involves the use of rodents that are viral antibody free, which are not as clean as the immunocompromised rodents.

“Traditionally, animals of different health status or species were held in separate rooms,” she says. “Today, ventilated racks and the use of biosafety cabinets have made each cage an actual room for rodents. Nothing goes from cage to cage. Therefore, there is no need for an additional room. One big space will allow you to maintain the different statuses in the same room.”

Cunneen says the only reasons to consider separate housing rooms are if rodents are not of the highest health standard; if you believe researchers and staff will not comply with the biosecurity rules; or if the facility will be required to house mice colonies without rederivation, a procedure that creates pathogen-free rodents.

Key cards to limit access—granted based on research necessity and not position or title—and the use of cameras can increase security.

While the theft of intellectual property may be a concern, Cunneen says most proprietary drugs or experimental solutions arriving at an animal care facility are created in a secure lab, and are usually marked with a code that does not divulge any secret information about the formula. Simply using a syringe marked with this code in a room shared with other researchers should not cause any concern. However, it is not a good idea for researchers who are developing a new bio-implantable or surgical method to share a space where others can view their work.

By Tracy Carbasho