The need for more space to accommodate a daily backlog of unwashed cages sparked a $40 million gut renovation of the two-building animal research facility on the campus of the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI) in Bethesda, Md. When the conjoined structures reopen this fall, they will be fully equipped with up-to-date features that facilitate animal care compliance, promote employee satisfaction, and offer uber-flexibility.

Totaling roughly 52,000 gsf, Buildings 43 and 47 are part of the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, the military’s medical college, located on the grounds of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. The AFRRI campus consists of seven interconnected buildings constructed in an as-needed fashion from 1962 to 1978, creating a maze of disorganized space.

“Labs were interspersed with offices interspersed with radioactive spaces. Redundant services were common across the building types,” says Lawrence Wright, an architect with LEO A DALY. “For example, you would walk into one building and find an elevator right there. Just 10 feet across the hall was another elevator, and then 20 feet further on the other side was yet another. They were there because the various structures were built at different times to different heights. They were desperately in need of some type of organization.”

New and Improved Cagewash

The initial driver of the AFRRI renovation was the inability of Building 47’s cagewash operations to keep up with the daily volume of dirty cages. User complaints had spawned a request for a building addition to accommodate the backlog. After conducting their facility assessment with a more holistic perspective, the architects determined that a combination of more and faster machines and more square footage would alleviate the problems.

Wright notes that it wasn’t so much the continuously running tunnel washer, with its processing time of roughly three minutes, that was slowing down production. Rather, the bottleneck was the large cage and rack washer, which had a 45-minute cycle time.

The remedy was to replace the large single unit with two larger and more efficient double-rack washers, custom designed by supplier BetterBuilt®. Measuring roughly 6 feet wide by 14.5 feet long (twice the length of standard machines), the rack compartment accommodates two large cages or two racks at once. Its super-efficient operation slashes half an hour off each clean cycle, with double the output.

“The new cagewash equipment provides a capacity of 12 cages—three rooms’ worth—in less than an hour,” says Wright.

With more space in the cagewash, AFRRI was able to address another unmet need, a sterilizing capability for cages when changing between animal populations. Instead of incorporating a vaporized hydrogen peroxide cycle into the cage washers, which could create a potential hazard for workers in the area, the planning team opted for two custom-built steam sterilizers from PRIMUS®.

“Most of the steam is contained within the unit, but there was concern that after a cycle some lingering steam might escape,” says Wright. “We positioned hoods over the doors with exhaust fans to draw the steam out of the building.”

Slow washer throughput wasn’t the only impediment to productivity. The layout of the cagewash area was also a source of frustration to employees. A mistake made in the installation of the tunnel washer several years previously caused it to operate in reverse order to the building’s clean and dirty circulation. Dirty cages were wheeled in next to the clean elevator, and clean cages exited by the dirty elevator.

The design team took advantage of the need to revise the circulation path and expanded both clean and dirty sides into adjacent space that was no longer being used as originally designated. For example, isolation rooms were no longer necessary as isolation of incoming animal populations was taking place in individual animal rooms upstairs. The space occupied by the large central food and bedding storage room was freed up when the contents were dispersed to newly created smaller storage rooms on the second and third floors, putting the facility in compliance with the mandate to separate all species-specific supplies.

In total, both dirty and clean cagewash areas almost tripled in size, from 600 sf to 1,750 sf and 550 sf to 1,400 sf, respectively.

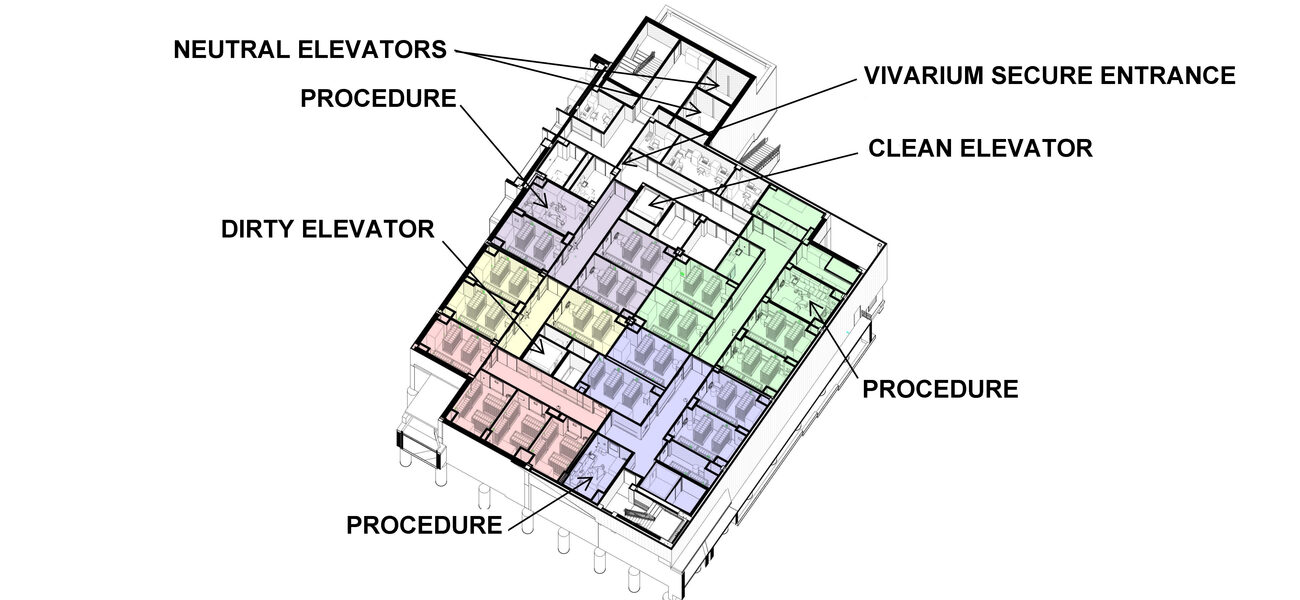

Circulation was eased and the risk of contamination was reduced by two other changes. A 1,682-gsf addition was built to house a pair of neutral elevators and a stairway, so vertical circulation could take place outside the main spaces of the vivarium. Relocated locker and shower rooms afford direct access to the clean elevator for PPE-garbed personnel, also safeguarding the barrier.

Animal Room Flexibility

AFRRI researchers work with three different species. A major precept guiding the renovation was to future-proof the vivarium by designing in flexibility. To that end, all the second-floor animal rooms can house either of two species, depending on the population size. Given that each species has different environmental needs, the HVAC system is sized to accommodate the heaviest possible population load.

“In theory, on one side you could be working on one species and on the other side you could be working on another,” he says.

Procedure Room Flexibility

Flexibility is incorporated in the three procedure rooms as well, each serving a different set of animal rooms. Two procedure rooms are species-specific, while the third can flex with swings in the population.

Another insightful strategy the architects used to future-proof the facility was to allocate the same square footage to both animal and procedure rooms. Acknowledging that procedure rooms might typically be smaller than the 212-sf holding rooms, Wright points out that making them the same, larger size extends their utility.

“A procedure room could operate well in less square footage, but it probably wouldn’t make a good animal room in the future,” he says. “This way, AFRRI won’t have to tear down something or build an addition. The procedure rooms are all prepped to become animal rooms—just remove the casework. They have the same finishes, the same drain at the back, and the hose bib at the front, just like an animal room.”

He also emphasizes that this type of foresight might not be immediately obvious in the planning process, but it pays dividends:

“This requires a little bit more thinking when you’re programming a new facility, because the tendency is to try to shrink things in the smallest possible envelope they can be in.”

Surgery Suite Flexibility

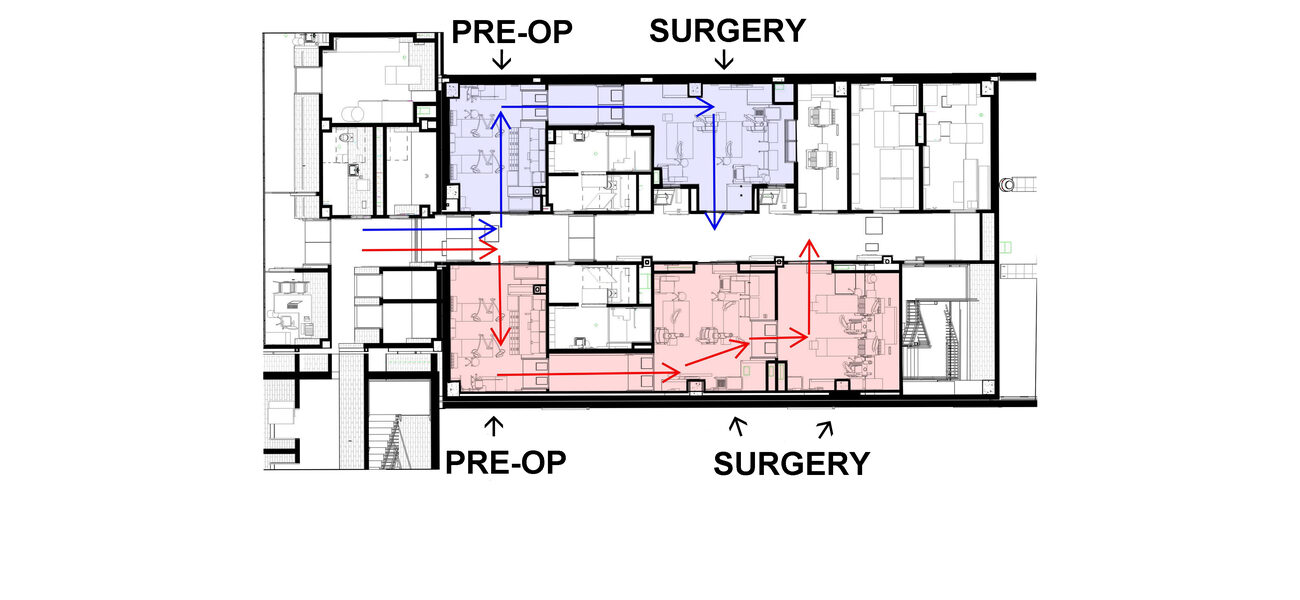

The top floor of Building 43 houses two new, different-sized surgical suites, across the corridor from each other. The larger one has two adjoining surgery rooms, but both suites are equipped with a separate pre-op room and a service corridor at the back to wheel the animals into the main surgery. This layout provides for the separation of the species while also enabling either suite to service any of the three species.

Assessment and Master Plan

Arriving at the new, more efficient design was a challenge.

Chartered to research the effects of ionizing radiation and devise ways to treat injuries (its therapies helped victims of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi reactor accident), AFRRI was “coming up against that 50-year lifespan where major facility overhauls and renovations were needed to continue to be useful,” explains Wright.

The architecture firm conducted an assessment of the campus and prepared a master plan for reorganizing the 200,000 sf of program space. With their aging, sorely taxed infrastructure, Buildings 43 and 47, which served as the vivarium space for the entire research complex, emerged as the most pressing renovation target. A plethora of deficiencies—ranging from a lack of seismic reinforcement to inefficient HVAC systems to the absence of handwashing sinks in animal rooms—hampered employees and threatened the facility’s AAALAC (Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International) accreditation.

While AFRRI’s preference was for new construction, complex and time-consuming Department of Defense requirements made renovation a much quicker path—a matter of months vs. years to get Congressional approval to build new. The sustainability advantages were compelling as well: Wright calculates that by saving just the structure of these existing buildings, about 2 million kilograms of CO2 were prevented from entering the atmosphere—the rough equivalent of 5 million miles driven by 434 passenger cars in a year.

Interior Demolition

First completed in 1963 and then expanded twice in the following two years to its current 17,840 gsf, the three-story Building 43 was AFRRI’s original vivarium. In 1978 it was replaced by an adjacent new vivarium, the four-story, 33,707-gsf Building 47. Today, Building 43 serves mainly as support, with histology and pathology labs on the second floor and the surgical suite on the third. Building 47 houses the central cagewash on the ground floor and animal and procedure rooms above.

A nine-month gut renovation stripped all mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and communication equipment from both buildings. While existing finishes, including epoxy floors and epoxy wall paint in the vivarium, were also removed, where possible the architects kept many of the concrete masonry unit (CMU) walls in the vivarium.

“This was a cost-saving measure since they would be more expensive to replace,” explains Wright.

The concrete slab under both buildings was one component that was judged not worth saving. The cagewash in Building 47 was being expanded and refurbished, with extensive new plumbing required. There was so much new utility work to do under the slab, especially to distribute the plumbing and the main electrical feeders, that it was more cost-effective to remove the existing floor slab and entirely replace it.

Creative Solutions

The mid-century modern design did not always lend itself to the changes required by updated building codes, AAALAC guidelines, and new technologies.

“Modern day science buildings are usually 15-plus feet floor to floor,” says Wright. “Building 47, state-of-the-art in 1978, only used about a 14 feet 4 inches floor-to-floor height, and the upper floors were only 12 feet 4 inches floor to floor.” The resulting ceiling height of 8.5 feet created “a compressed plenum and less space than desired for distributing the utilities required to keep the animal rooms running.”

The designers countered this obstacle by mounting raceways for electric and telecommunications cabling high on the walls of the hallways. Wright comments that although the overhead space is still like “congested spaghetti,” the partial solution definitely helped free up room above in the ceiling.

The raceways were only one of the creative solutions the project team was challenged to devise.

In one area, as part of seismic reinforcement, Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) strips were glued down with polymer to add tensional strength to the existing concrete slab.

“In an existing building, you can’t just throw more rebar into the slab to make it stronger, so this is a good solution,” says Wright. “It has the bonus of not taking up a lot of space, plus it’s not very destructive. You don’t have to chip up concrete.”

Another structural retrofit entailed installing steel beams to support the load of a new walk-in cooler destined for the floor above.

Ease of access to equipment for servicing was much less of an issue when the buildings were planned, but today’s more intense HVAC and IT systems come with new demands for accessibility, especially in a limited-entry facility like a vivarium.

The redesign created individual electrical, communications, and HVAC rooms, stacking them on each floor. The centralized locations streamline access to equipment control panels and servers for technicians, who can now get their work done without having to enter sensitive areas of the buildings.

Energy Improvements

With AFRRI’s mandate that the renovation meet LEED v4 criteria, energy efficiency in a building with single-pass air was an imperative. Installed in the penthouse, the three HVAC units that service Building 47 incorporate a membrane heat transfer technology from York that mixes intake air with the exhaust air stream, reducing the energy load required to get supply air to the correct temperature.

An adaptation of the heat wheel transfer technology in use for several decades, the membrane approach is a good solution for facilities that discharge 100 percent exhaust air, which could spawn concerns about microbiological contamination, says Wright.

“The membrane keeps the streams from mixing, but heat can still transfer,” he explains. “It is useful technology in science lab buildings. I don’t know of any other building typologies that use it.”

Other energy saving features include employing LED lighting—“the new standard,” says Wright—throughout the entire facility; the installation of an air barrier on the exterior walls; and an upgrade of the exterior metal panels.

“As a result of all the energy improvements that we made, this building scores about 26 percent better than a baseline model building of similar size,” he says, noting that it is currently registered with the Green Building Certification Institute and is on track to achieve the Silver rating.

Wright concludes by affirming that with a facility master plan driving funds to the right places, creative workarounds to construction challenges, and an emphasis on flexibility, “it is completely possible to renovate any mid-century modern research building to meet modern-day requirements.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

LEO A DALY

|

Architect

|

|

Life Science Products Inc.

|

Crash Rails, Door Guards, Vivarium Ceiling System

|

|

Dudick, Inc.

|

Specifications for Crash Rails, Door Guards, Vivarium Ceiling System

|

|

Allentown Inc.

|

Ventilated Cages

|

|

Better Built / Northwestern System Group

|

Cage and Rack Washer

|

|

PRIMUS Sterilizer Co., LLC

|

Steam Sterilizers

|

|

York

|

Membrane Heat Transfer Devices

|