Colleges and universities are rethinking their workplaces to align their space with how people work today and to use space to achieve their strategic goals. Beyond macro forces reshaping higher education in terms of access, accountability, and financial stability, there is a confluence of financial, environmental, technological, and cultural factors prompting this change, including increasing numbers of administrative staff and a growing disengagement among faculty and staff.

According to Gallup, only 33 percent of university faculty and staff are engaged at work—“involved in, enthusiastic about, and committed to their work and workplace.” At the same time, office space on a per-student basis has increased 153 percent since 1974, according to the Education Advisory Board's "Recalibrating Allocation and Size of Faculty Offices" 2016 Facilities Forum report. This is not surprising, since professional administrative staff at colleges and universities increased 38 percent from 1990 to 2012 at public universities and 42 percent at private, non-profit universities, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Based on all of these factors, institutions are rethinking their workplaces to achieve at least seven different goals.

- Achieving the highest and best use of space: Colleges and universities recognize that spaces at the center of campus are often their most valuable, and that the value of physical space is to enable collaboration, foster interaction, and build relationships. So, many are moving groups with little or no contact with students and faculty—such as HR, advancement, purchasing, and facilities—to the periphery or off-campus. This frees up space for classrooms, study areas, student services, and research labs.

- Responding to new work patterns: Most academic workplaces are primarily individual desks and offices for individual work. But people are working more collaboratively in teams; have flexible schedules; and are more mobile, working wherever they are, including at home, rather than just at their desk. This increase in collaboration has borne tangible results: The average number of authors per paper grew 38 percent, from 3.2 to 4.4, from 1996 to 2015, according to The Economist. So, more collaborative and flexible spaces are needed.

- Increasing campus space utilization: When colleges and universities invest in their campus, they want to ensure their assets are fully utilized and meeting the needs of their students, faculty, and staff. Low utilization can be an indicator of a poor-quality space, a surplus of space, or both. Office space is among the least utilized and unfortunately the least scrutinized. Most assigned offices are occupied only 30 to 40 percent of the time during a typical workday and often cannot be used by other people when its occupant is out—teaching a class, working in a lab, in a meeting, traveling, or working from home.

- Increasing financial feasibility: While people costs far outweigh space costs, space is expensive to build, operate, and change, particularly when factoring how much it is used. According to a metric developed by brightspot strategy to determine “cost per person per hour utilized,” a 140-sf office with 30 percent utilization by one person is 9.4 times more expensive than a typical classroom with 25 sf for each person and 65 percent utilization. (Input on the calculation was provided by Sally Grans-Korsh, FAIA, director of facilities management and environmental policy at the National Association of College & University Business Officers; and Jeff Ziebarth, principal at Perkins+Will.)

- Achieving environmental sustainability: Colleges and universities want their spaces to not only be well utilized and financially feasible, but environmentally sustainable, as well. Buildings in the U.S. account for 39 percent of our carbon footprint. New kinds of work environments with more shared space and more open space require less space per person, which is more sustainable. While more efficient spaces that are used more intensively may consume more energy per square foot, this is offset by the ability to build a smaller facility.

- Promoting student/faculty interaction: Contact out of the classroom between students and faculty is a critical driver of student engagement, according to the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), but only 40 percent of freshman have had such an experience. This is in part because faculty offices can be isolated, inaccessible, or intimidating for students—institutions wonder why students don’t go into something called a “faculty office building.” So, colleges and universities are rethinking faculty offices to allow faculty to get their work done while also being accessible to students.

- Enabling concentration at work: In many cases, the primary rationale for an office—having a private, enclosed space that enables quiet, focused work—is undermined in practice because colleagues, staff, and students visit and interrupt, anyway. In fact, many universities have an open door policy to ensure faculty and staff are accessible to students. In effect, many people have an office with a door so that they can keep it open. Hundreds of conversations with faculty and staff have revealed that they actually do their focused work at home, in a coffee shop, or in the library to avoid these interruptions.

What is the Range of Workplace Innovation Taking Place?

One way of thinking about how the workplace has changed is to see that the same set of ideas is diffusing across sectors at different rates, depending on the applicability of the forces for change and how resistant an industry is to change. More than 20 years ago, consulting organizations moved from assigned offices to a variety of unassigned spaces in response to how little time people spent at the office and how much of their work happened in teams. These strategies have long since been adopted in sales organizations, financial services, and pharmaceuticals, and are just now hitting law firms; for instance, Minter Ellison, an Australian firm, moved to an unassigned, activity-based work environment. Higher education is clearly next.

Likewise, within higher education, there is a similar segmentation of different user populations that determine how quickly new workplace concepts are adopted. Administrative staff are often the first to adopt, because they follow their corporate counterparts most closely and are subject to institutional hierarchy. The next tier includes adjunct, part-time, and clinical faculty, who are on campus less, more mobile, and lower in the pecking order. They also may openly acknowledge the need for a new model based on their work patterns, such as clinical faculty members in a medical school who spend most of their time seeing patients and teaching courses. Full-time tenure-track faculty are the slowest to adopt or the most resistant to change, due to a lack of hierarchy, a more traditional orientation, and need for spaces that accommodate both focus and private conversations.

There is also a spectrum of workplace changes that ranges from easy to hard to implement. The easier end of the spectrum is to provide smaller, enclosed offices complemented by shared meeting spaces to recognize how much more work happens in teams. For instance, Gensler’s 2016 global workplace survey showed that among corporate workers, people spend 47 to 54 percent of their time collaborating, but a typical university will allocate 64-sf desks and 120- to 240-sf offices, but only 15 to 20 percent of their space for meetings. Even though collaborative work often takes less space per person than individual work, these proportions are off if people are spending about 50 percent of their time in 20 percent of their space. The next tier of change is moving from assigning enclosed offices to an open plan, with groups of desks within larger shared open spaces that are complemented by a variety of enclosed spaces for private calls, meetings, and events. The next and most difficult tier of workplace change is moving from assigning spaces to specific people to instead giving people the flexibility and choice to work where, how, and when they want—often called an “activity-based workplace” or perhaps more coarsely as “hoteling.”

What are the Best Examples of Academic Workplace Innovation?

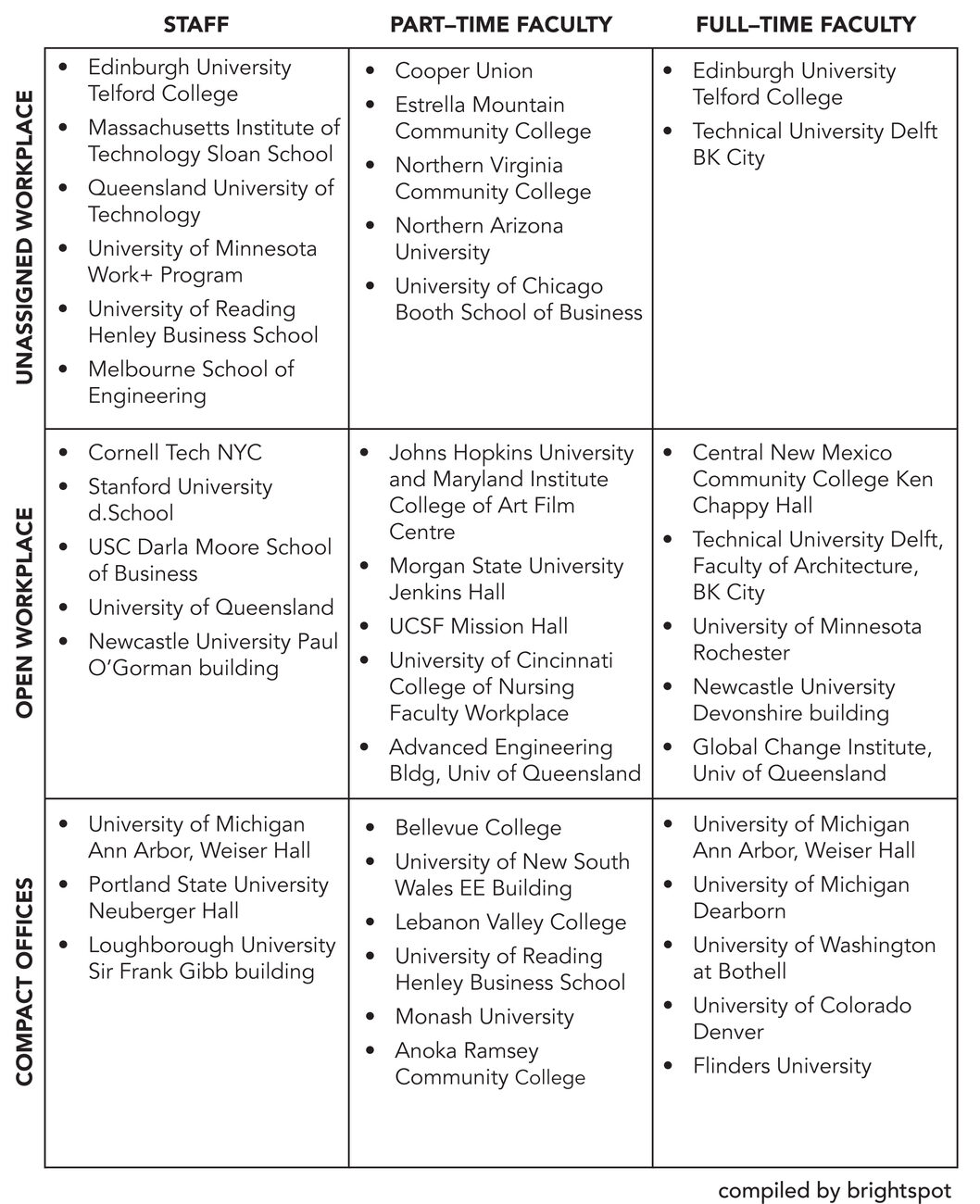

To understand the changing landscape of academic workplaces, we can take these two factors—who the workplace is for and the degree to which it is changing—as axes on a grid. In the first grid below, we have illustrated the concepts with examples. The second grid lists examples in each category that brightspot has been involved with or that they’ve been able to identify in their research. While not comprehensive, this provides a sense of which strategies have been employed where and for whom; brightspot is continuing to study the transformation of workplace innovation, and welcomes comments, additions, and clarifications to this evolving list.

Flexible Working at the University of Minnesota: brightspot developed Work+, a campus-wide activity-based workplace program for people to enjoy greater flexibility and more choices as to where to work. This arrangement increased productivity by 14 percent and reduced response times by 69 percent in 30 percent less space in initial pilots with the Office of Human Resources and University Facilities groups. (Design credit: University of Minnesota)

Open Plan Faculty Workplace at the University of Minnesota Rochester: A visionary president took an innovative, shared space approach to develop a new health sciences campus. For instance, in lieu of building an athletic facility, students have memberships to the local YMCA. Faculty were recruited with the expectation that they’d work in a new kind of environment: open office faculty suites with adjacent student meeting and collaboration spaces. (Design credit: HGA Architects)

Collaborative Workplace at the University of Michigan Weiser Hall: brightspot reimagined an existing, unloved, double-loaded cinder block corridor building as a flexible, collaborative workplace with a variety of assigned and shared settings for work. The results were greater than 75 percent satisfaction with spaces, technology, and furniture, as well as productivity gains of 4.26 hours per week, on average. (Design credit: Diamond Schmitt Architects)

Unassigned Staff Workplace at the MIT Sloan School of Management: brightspot worked with the school to create an activity-based workplace that brought together previously distributed Executive Education staff. This change provided them the flexibility to choose where and how to work within less space overall, while enabling the collocation of several groups. (Design credit: Stantec)

Open Faculty Workplace at the University of Cincinnati College of Nursing: To test a new workplace concept, the college renovated an existing floor to create an ecosystem of individual and collaborative spaces for more transient clinical faculty, including 6-by-8-foot dedicated faculty workstations, shared meeting rooms, and dedicated offices for some faculty. (Design credit: SmithGroupJJR)

Open Faculty Workplace at the Johns Hopkins University and Maryland Institute College of Art: Johns Hopkins University and Maryland Institute College of Art created a workplace for full- and part-time faculty shared across the institutions, including a mix of open workstations and enclosed offices for faculty, and informal communal work areas. (Design credit: Ziger/Snead Architects)

Open Faculty Workplace at Central New Mexico Community College: CNMCC renovated Ken Chappy Hall to convert a portion of the building from classrooms to faculty workspaces, and to test a new concept in the process: The design includes open workstations for faculty, along with adjacent shared focus rooms and a variety of meeting and informal spaces. (Design credit: Dekker/Perich/Sabatini)

Open Faculty Workplace at Morgan State University: The university created a new Behavioral and Social Sciences Center that includes an open workplace for part-time faculty and graduate instructors that is adjacent to student collaboration space, as well as enclosed offices for full-time faculty. The adjacency of faculty workspace to student collaboration space intentionally promotes interaction among and between the groups. (Design credit: HOK)

Unassigned Faculty and Staff Workplace at Edinburgh University: In 2006 Edinburgh’s Telford College relocated to a new campus in the city’s Waterfront development, bringing together three campuses, 20,000 students, and 600 staff under one roof, all sharing resources and learning experiences. Among the most radical of models, the space is primarily shared (i.e., unassigned) open workspace: 85 percent of staff/faculty share space, with an overall average of one desk for every two people. (Design credit: HOK)

Unassigned Faculty and Staff Workplace at the Technical University Delft: Following a devastating fire, the Faculty of Architecture at TU Delft renovated their facilities and created an open shared workplace for faculty to work together and experiment with new workplace models within their “BK City” complex. Faculty and staff use a variety of assigned and unassigned spaces that are open and enclosed. (Design credit: Kossmann de Jong)

How Can Colleges and Universities Rethink Their Workplace?

The most common mistake that institutions make when trying to change their workplace is assuming that they are trying to solve a space problem. Even if the impetus for a project is a space problem—you’re out of space and have no place to put the new faculty or staff member you just hired!—you won’t solve it by thinking about it that way. It’s more complex and nuanced than that. What you need first is a workplace strategy, a coherent statement that describes how your space will be used to help you achieve your larger strategic goals. For instance, if student success is a goal, and we know student/faculty interaction is a major contributor to it, then your workplace strategy might be to maximize student/faculty interaction while enabling faculty to focus.

Having a workplace strategy means you can think about space and people simultaneously, and this is the best way to orchestrate the process. (See the process map below.)

- Vision and Direction: Start by defining goals (e.g., maximize student/faculty interaction) and set the vision and direction. Use this direction to design a change program that will identify the shifts people will have to make compared to today and the ways you can support this transition through communication, training, and other activities.

- Future Needs: Then define the future workstyles by role and future needs in terms of space, technology, furniture, and support services.

- Participatory Planning: Once these are articulated, you can co-create the solutions to meet the needs and build buy-in, and then look for ways to prototype the future by building mock-ups to look at proportions, sightlines, and furniture options. Pilots with actual work settings people can work in for a day, week, or month, are also a great change management tool.

- Reflect and Refine: Once built, you should measure the performance of the workplace against your initial needs assessment and tweak spaces, operations, and policies based on the findings.

Tips for Getting Started

Once you understand the process, there are strategies to help increase your chance of success. First, find groups that are willing to try new things, as these could become a pilot project to learn and get others on board—business schools, academic health centers, or entirely new programs with visionary leaders are often the best opportunities. These are often the groups that are the most mobile—they spend the most time away from their desks because they are seeing patients or meeting with partners—and they are the most tied to industry and thus aware and receptive to trends in how the corporate workplace is changing. Second, given the rise in part-time faculty, as well as the trend to move administrative units off campus, another opportunity is for colleges and universities to create a shared work environment, like a coworking space, for its more mobile workforce, which gives people based off site a place to connect and be productive on campus while giving the institution a chance to test new space concepts. Coworking juggernaut WeWork, for example, just opened its first academic coworking space at the University of Maryland University College. Third, another way forward is for universities to update their space standards to result in savings by reducing the sizes of offices and workstations, while still increasing the amount of space devoted to collaboration.

As new workplace strategies are adopted, organizational change management is crucial to enable people to be informed, excited, and prepared. Faculty and staff need to know what’s happening and why. Colleges and universities need an intentional process for setting norms and building the skills people will need, rather than moving them to a new space and hoping they will miraculously work differently without any training or discussion about how to do so. As they implement changes, institutions need to keep in mind that changing the workplace isn’t simply a “space problem.” It is much more complex, involving institutional goals and strategy, culture, work process, organizational design, and support services, to name few. A holistic approach is a must.