Using the Lean continuous improvement process to increase efficiency and productivity is seen frequently in the manufacturing and automotive sectors, but less often in animal research facilities. Those who have used Lean to overhaul animal facilities say there is a lack of understanding in the industry about how this methodology can drastically boost efficiency, lower operating costs, decrease waste, improve sustainability, enhance program flexibility, increase capacity, and lower space requirements.

“I don’t think people at senior levels within organizations understand that animal facilities are process facilities,” says Chris Cosgrove, CEO of The ElmCos Group Ltd., a British Columbia-based company that provides consulting services to the lab animal industry. “If they were building a manufacturing plant, they would be asking for help from somebody at GM, Ford, or Toyota, but they don’t think about Lean with animal facilities. We are just now bringing this thinking into animal facility operations and design. This is an industry ripe for disruption.”

Cosgrove stresses that animal facilities are not like other labs, but are process facilities similar to factories, with specialized equipment, processing items, and a flow of people, materials, and animals. He suggests consulting Lean experts prior to the programming phase of a renovation or construction project to ensure the vivarium will deliver value. Embracing Lean early and applying it to existing facilities could help identify efficiencies that may influence program requirements and decisions about whether to build new, renovate, or simply modify existing operational models.

“We need to start thinking about introducing processes into how we lay out spaces,” says Cosgrove. “When we create designs for spaces, they should be dynamic layouts, not static layouts. That way, when you open a building, you won’t have to develop operational workarounds to deal with issues that should have been addressed in design by taking the processes into account.”

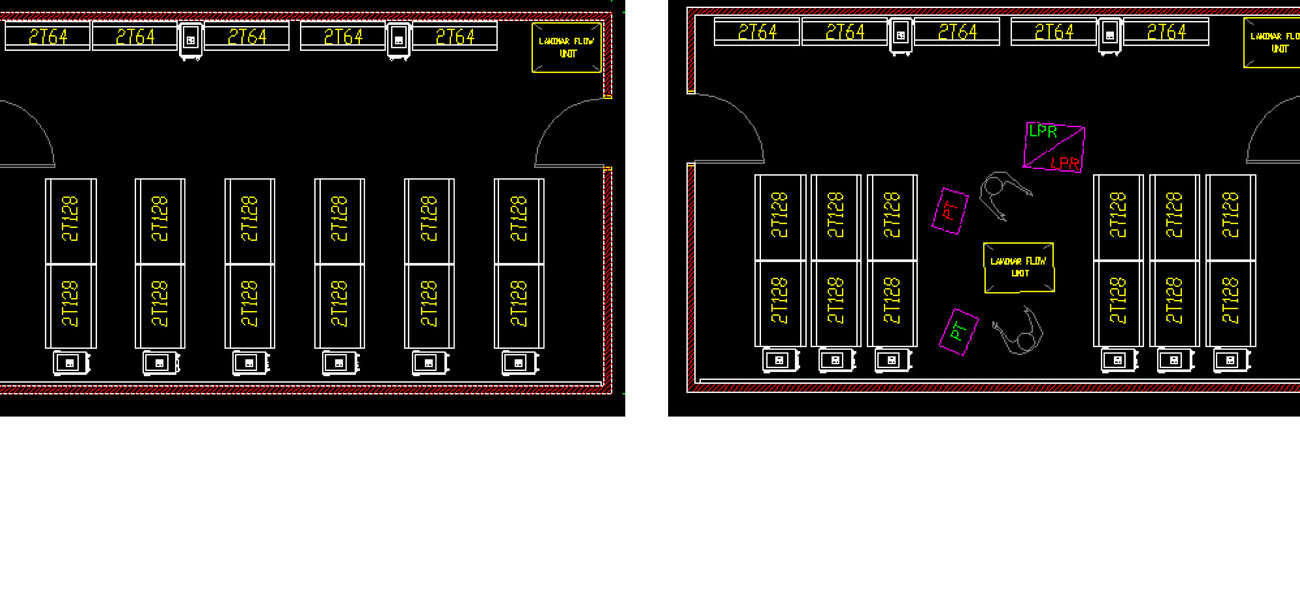

Using a dynamic layout enables planners to visualize and simulate how tasks and processes will be completed when the facility is operating, and how much space is needed to perform procedures, rather than creating static models that show the placement of equipment and furniture when the space is unoccupied with no inclusion of the flow of people, processes, and animals. Building on this concept, simulation software can be used to animate processes to assist with the optimization process.

A process-driven design with dynamic layouts can show the distance people travel when performing tasks, and reveal ways to minimize the time and motion required to complete the task.

University of Houston Optimizes Processes and Facilities with Lean

The University of Houston used a process-driven Lean approach to clean and organize its animal care facilities, and continues to apply the principles to prioritize tasks, reduce waste, control inventory, enhance processes, improve productivity, maximize space utilization, and leverage employees’ full potential.

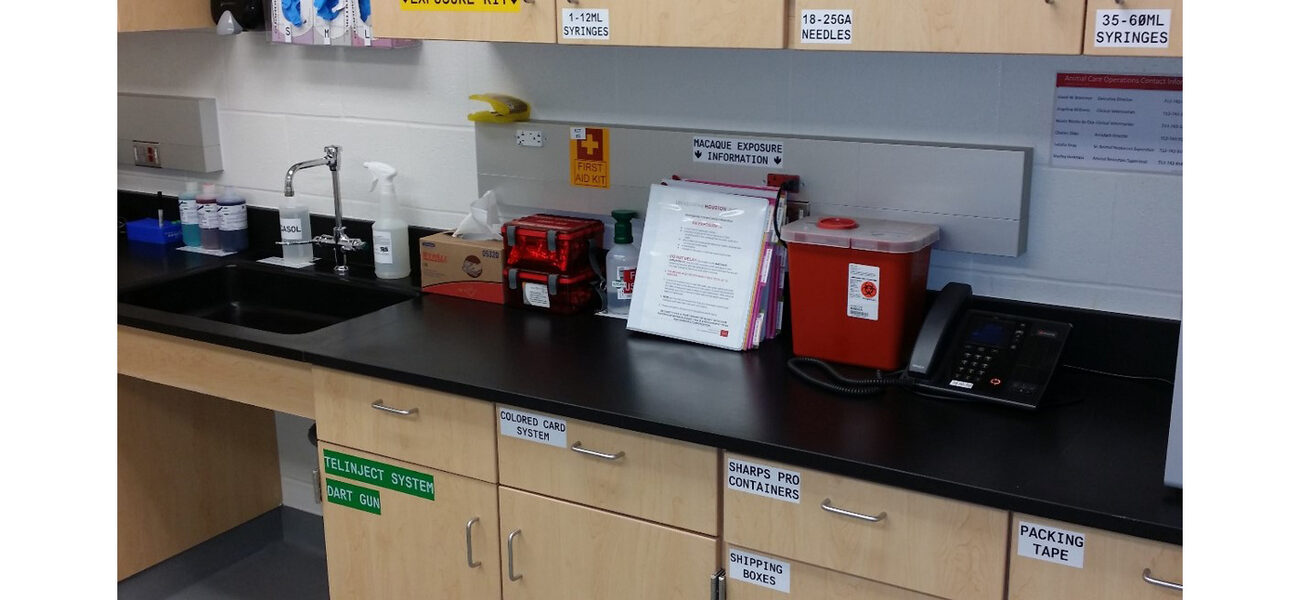

Planners in the university’s animal care department embarked on Lean by using the 5S methodology of sorting, setting in order, shining, standardizing, and sustaining to organize the vivarium and properly allocate space. They started by sorting every item, so they would know precisely what they have, and then they set each item in the location where it would be used to minimize the amount of walking needed to retrieve it.

Shining means ensuring every item is functional, and if it does not work, it is repaired or replaced. Standardizing equates to using the same biosafety cabinets, the same disinfectant agent, and other materials and equipment throughout the facility. Employees are trained using the same equipment and cleaning methods, so they can function throughout the facility, and keeping items organized becomes part of their work routine. It is easy to sustain a clutter-free, functional work environment when the 5S methodology is part of the culture.

“When we started, there were 28 animal rooms and everything was lost, misplaced, or just random,” says David W. Brammer, executive director and chief veterinarian of Animal Care Operations at the university. “We had an overabundance of oxygen tanks, storage containers, cardboard, and cages.”

The cultural transformation at the university began with the 5S program and slowly transformed the workplace into an orderly and efficient animal facility. The changed culture can now be summarized with a sign that states, “No location, no label, no storage.” Items can only be placed in the designated storage areas if they are labeled, and it is now easier to locate materials. Hallways are free of clutter, and all machinery is equipped with a visual work procedure, outlining the instructions for operating the machine.

The university achieved inventory control—an essential part of Lean management—by purchasing red bins and dedicating each one to a disposable item. Each bin has a sticker indicating the location of storage, and the product information required to accurately reorder, store, and access the item. A vendor replenishes the items when necessary.

“This replaced the entire ordering system; now we order only the items consumed rather than buying in bulk, storing, and reordering when the stock is presumed to be too low,” says Brammer. “We moved from bulk ordering and storing to a steady state inventory that replenishes at the consumption rate. The variation between what we were ordering and what we actually needed dropped from 37 percent to 5 percent.”

Organizing materials and controlling inventory enabled the university to move into two 25,000-sf animal facilities with less than 100 sf required for storage of disposable items in each facility. Cage processing is also more efficient, with cages being processed today and stored with mice in them for use tomorrow, rather than preparing numerous cages in case they are needed.

Lean Impact on Employees

One goal of Lean management is to improve an organization’s overall operations by eliminating eight types of waste:

- Over-producing more products than required

- Unnecessary motion of people or information that does not add value

- Not utilizing the full potential of employees

- Waiting for someone, information, materials, or an event to happen

- Transporting materials, equipment, or information more than necessary

- Defects caused by errors and subsequent need for rework

- Over-processing more than required where a simple approach would have been sufficient

- Accumulating information, parts, or materials in excess of what is needed to complete the expected production goal.

The University of Houston also documented all of the daily tasks completed by employees, determined what items they were spending the most time on, and prioritized the actions that should receive the most attention. The tasks were prioritized based on effort.

“A lot of people have misplaced priorities, and they end up solving problems that don’t have any influence on their entire process,” says Brammer. “This is related to the 80/20 rule. You should spend your time making 80 percent of your effort more efficient, rather than spending time solving an issue that takes only a small amount of the effort. It is likely that five or six items consume 80 percent of the effort with the rest of the items only consuming 20 percent of the work. The best practice is to ignore the many items that consume only 20 percent of the work.”

The University defined 38 tasks that are done in a rodent animal facility and determined that employees deal with the animals only about 15 percent of the time. The bulk of the time is spent doing other tasks, such as cleaning and moving things. Employees are hired from other industries and do not always have experience working with animals. One employee previously worked in a restaurant and understands the importance of efficiency. Brammer welcomes ideas from employees about how processes or spaces can be improved as part of a bottom-up management approach that encourages everyone to contribute.

Maximizing efficiency may require employees to work differently in order to meet both quality and quantity of work expectations. Each technician was taking between 80 and 120 minutes to change 100 mouse cages. Using a dual-side change-out system, which requires more floor space, enables two technicians to work together to change the same 100 mouse cages in 45 minutes.

Using Lean often requires organizations to validate or disprove employees’ assumptions about how they might be impacted by a change. Cosgrove, whose company did not work on the University of Houston Lean implementation project, recalls one client that was considering changing from a bottom-only cage changing process to a complete cage change system. Employees assumed the new system would not work, but had no factual information to support their opinion.

The client conducted a study to test the assumption while using various configurations of fixed or mobile hoods for both cage changing systems. A reusable feeder was added as a variable. Additional steps were required with the complete cage changing system, but reusing the feeder reduced the workload. The complete system requires less workspace and smaller hoods, and is better for preventing cross contamination. Overall, addressing the employees’ assumptions through a data-driven Lean approach enabled the organization to move forward with its project.

Why Animal Facilities Are Ready for Lean

Lean represents a culture change, which typically is implemented in incremental steps to obtain stakeholder input and buy-in. Brammer and Cosgrove say the animal research industry is ready for Lean innovation, because the current business model is outdated, the funding system is inequitable, there is a high degree of technological change, and there are too many complex and expensive regulatory reporting requirements that waste time and money.

“There’s hesitation to change because of the fear of the unknown, but going through these Lean processes helps you feel more comfortable with trying new things,” says Cosgrove. “For an industry as cutting-edge as researchers who are developing new platforms and new technologies, we don’t change much in terms of how we build and operate our animal facilities.”

A high degree of technological change is occurring in animal facilities. For example, artificial intelligence is evident in smart buildings, smart processes and equipment, and specialized research platforms. Digitizing the animal environment will be the next major technological advance and part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, according to Cosgrove.

Digitization will inform technicians when a cage needs changing; communicate with suppliers about the inventory of cages, feed, bedding and other supplies; facilitate better inventory management; monitor the welfare of the animals and compliance to regulations; enable human resources efforts to be redirected to more value-added services; optimize space utilization; use data to advance best practices; and facilitate the optimum research by collecting data within the home cage instead of transferring animals to test cages.

“If you have a Lean culture, you will be well prepared to deal with these issues going forward,” says Cosgrove.

The Vivarium Operational Excellence Network (VOEN), an international organization that looks at benchmark processes, provides resources regarding Lean management tools and principles in animal facilities. While Lean principles are the same in every industry, the VOEN provides industry-specific information to make it easier to apply this method of continuous improvement to animal facilities.

By Tracy Carbasho

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

The ElmCos Group

|

Lean Process Consulting

|