The 21st century workplace offers multiple types of environments, and workers typically occupy an assortment of spaces throughout the day. How to get the right people in the right place at the right time to spark collaborations for creative problem-solving is more than just a question of corralling bodies. It’s a matter of creating the right kind of spaces and a path of least resistance toward utilization with the occupant experience as the prime focus.

When their immediate surroundings aren’t conducive to the task at hand, workers “vote with their feet” in search of a more appropriate setting, whether it’s a 3-by-3.5-foot phonebooth-type enclosure or an on-site coffee bar, says Melissa Marsh, founder and executive director of Plastarc. The technology that makes this mobility possible—primarily smart phones and WiFi—collects reams of data and measurements. Combining technology with a human interface in the form of a community manager who promotes building features and encourages a robust social network multiplies the power to design occupant-centric buildings with higher performing spaces and people.

“The ability of our buildings to data-collect has been around for quite some time,” says Brian Hopkins, director of Applied Computing, Ennead Architects, LLP. “Increasing sophistication allows architects not only to predict building performance but also to measure a prediction’s accuracy during occupancy. The idea is to enable people, more than buildings. Social data will become the information of design.”

Creeping Consumerization

Technology has dramatically changed the way humans do things in the consumer arena—using a digital wristband as a payment system, hailing a ride through a mobile app, or providing feedback on a movie they’ve watched. It is only natural that people want to find the equivalent of these lifestyle-easing features in the professional setting.

“We are in a moment of the increasing expectation of the occupant,” says Marsh. “The same experience that occupants have in the consumer world is becoming an expectation of the work and educational environments. What exists in retail now will be in the office soon.”

This move to the “consumerization” of the workplace is enabled by a digital layer delivering an array of “high-performance, customized, on-demand, and technology-integrated” services.

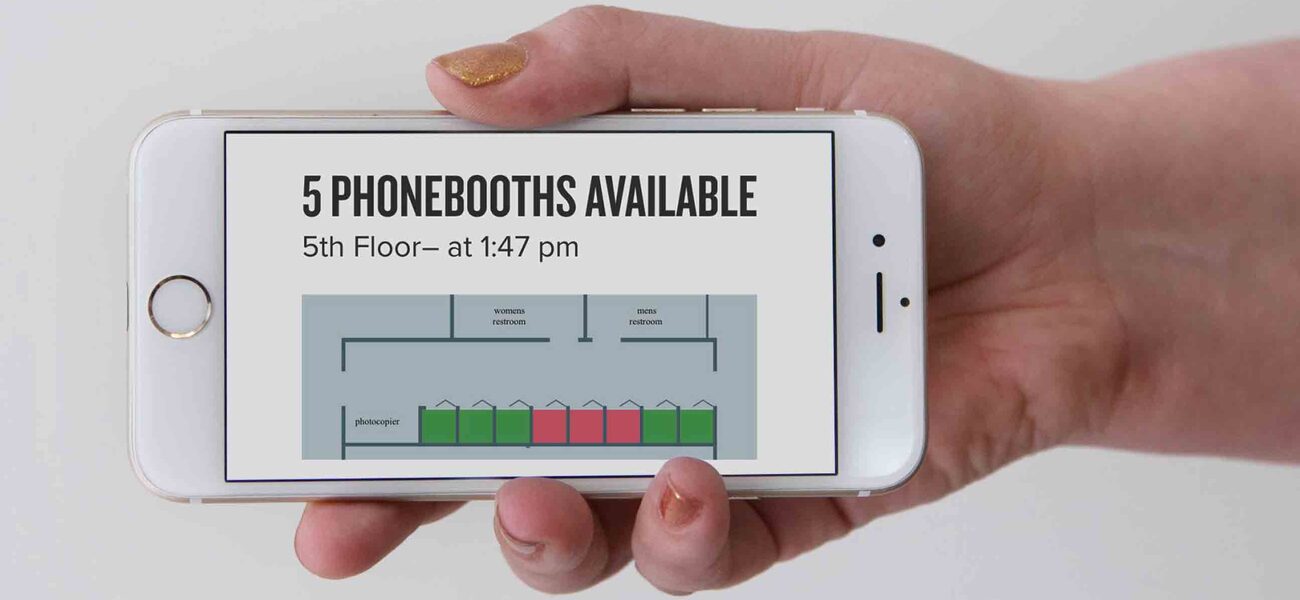

“The future is one of ‘changefulness’ through an increasing number of features that allow occupants to control and activate their environment by interacting through mobile apps,” she continues. Apps provide the ability not just to book a room and suggest meeting attendees but also to control the space configuration through the combination of technology and systems within the space.

“Furniture and fittings are more manipulatable by occupants than ever before, and will continue to advance through the use of technology,” she observes.

Community in Co-Working

The financial success of co-working enterprises, WeWork in particular, not only validates the business model but also confirms the primacy of the occupant experience in space planning and design. Instrumental in implementing the occupant-centric approach of the “pay-to-work” organization is the customer-facing community manager. This function is dedicated to helping users maximize the benefits of the building for individual performance, interaction with colleagues, and space utilization.

Somewhat akin to cruise directors or social media chat monitors, community managers spend most of their time interacting with occupants. They are taking on an increasingly physical role as they initiate activities and host events to engage occupants, making sure the space is serving them well.

Marsh cites this comment from a WeWork executive on the importance of the community manager role: “There needs to be someone engaging members, asking about their day, caring about their wellbeing. And then there is a digital service and social layer that builds on that physical experience.”

“What co-working organizations have been getting right is a focus on community enablement, rather than facilities management,” notes Marsh. “WeWork is selling a community, not a space. It is built to reinforce the experience of being in that environment and to feel that you are connected to the other members.”

Building as Social Enabler

WeWork is breaking new ground as a blended architecture and real estate organization, with a data collection infrastructure that allows it to fine-tune space performance while supporting occupant needs. The prime vehicle is the WeOS app, mandatory for all customers, which Marsh describes as “a data-driven social experience platform.”

“Anything that you can imagine needing to do in a work environment, you do through this app,” she says. The gamut of services ranges from the operational, like wayfinding or booking meeting rooms, to the social, such as seeing other members’ profiles, joining shared-interest groups, and building a network based on industry and sector—connections available by virtue of membership.

It makes the building “a social enabler,” an idea Hopkins first tested at Arizona State University, with an app designed to boost students’ connections with each other and their professors.

Essentially, the app’s vast repository of real-time data—use patterns, user preferences, user satisfaction ratings, environmental cycles, and more—serves as a predictive model, allowing the building to make “choices” by suggesting configurations “based on existing and anticipated states,” says Hopkins.

“These states are a collection of data where environment and social configurations intersect and where the building is actively adapting to augment these processes—for example, ‘hot rooming’ for meetings in real time, finding the right room (in terms of size, AV, lighting, etc.) for the meeting based on user schedules, drawing from user profiles to recommend collaboration potentials between staff members, and suggesting the right people and the right room.”

WeOS Feedback Loop

WeWork’s WeOS provides a treasure trove of spatial data with significant implications for utilization—and future innovation. With their always-on connection to the network, members are themselves sensors, and their usage patterns, along with requested feedback, constitute a running evaluation of how the environment is performing.

“Optimizing for utilization means it has to be a higher-performance environment for people to want to go there,” says Marsh. Occupancy becomes an expression of sentiment. “Are we providing spaces that people would rather be in? If they were given the choice between being there and not there, where would they be? This puzzle of occupancy is really about performance.”

The extent of the information collected permits WeWork to drill down into the subtleties of space usage. For example, a meeting room might be booked frequently, but never by the same occupants. This nugget of information is likely to pass unnoticed in traditional environments, but with WeOS user feedback, the design team could see that the room has a drawback—it might be too colorful or have an HVAC problem—that keeps repeat users from returning.

While social media apps and automated facilities task order systems already exist to capture this information, WeOS integrates them in a single app that the occupant can use for everything.

“This next level of detailed understanding—not just which spaces are being used but who is using them and what they like about them—adds to the ability to design and be predictive about future environments and serve our customers,” says Marsh.

It also enables WeWork to embrace a robust innovation cycle of trialing solutions, failing fast, and learning quickly with unprecedented rapidity, in the constant quest to improve the user experience.

Customer First, Then Data

At a time when occupant expectations will only increase, the notion of the workplace as a “platform of delight” is gaining traction. More than ever, corporate employers rely on the work environment and its services as a core of their attraction and retention policies. While some organizations continue to regard their space configurations as part of their IP, the shared workspace is much more public facing, open to guests and prospective member tours. With occupants frequently posting photos to social media, even more attention is drawn to interior appointments and amenities.

Marsh points out that, rather than focusing on finding occupancy data, the emphasis should be on uncovering what users really like.

“If you go looking for data, it is going to be a harder project than if you build something that enables people to get better service and have a better experience,” she says. “Then you focus on the exhaust data from that product.”

That knowledge gained from this type of deep dive will lead to higher performing buildings.

“As architects, we spend a lot of time thinking about how to incorporate applications that automatically give us this information,” says Hopkins. “We are not just talking about delivering a building, but a building with an application that is built on top of it. The new paradigm is buildings that are collecting data that are then learning user patterns and behaviors. That is how we can make better buildings, whether new construction or renovation.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl