Universities typically build or acquire new academic space sparingly, after long deliberation. When changing economic conditions dropped a whole campus into Lehigh University’s lap, the challenge has been to use that space in ways that support today’s education. Industrial giant Bethlehem Steel didn’t go formally bankrupt until 2001, but the writing was on the wall as early as 1987, when the company sold the majority of its “Mountaintop” research facility to Lehigh, which has since acquired two more buildings there, including Mountaintop C. That massive building’s three high bays attached to a curved bank of offices, is now home to student-driven projects in an environment that seeks to keep elements of the industrial feel and keep large bays as relatively rough, unfinished space.

Dan Lopresti, chair of the computer science and engineering department at Lehigh, was one of the first university officials to walk through Mountaintop C. “We found a 2005 calendar on the wall, and we took the building in 2013,” he says. “They left behind hundreds of computers, desks that looked like they had just been worked at, and dozens and dozens of file cabinets that were filled with files, thousands of engineering drawings, just everything left behind. It was quite an extraordinary scene.”

A traditional renovation might have taken years, but no one at Lehigh had time for that. “We decided this is really cool, but we have to start using it right away,” says Lopresti. The first step was to make the building safe, cleaning up one of the high bays and beginning a summer program called the Mountaintop Experience, where students develop their own initiatives, ranging from technology to film to social sciences. The first group of 20 students had movable whiteboards to use as space dividers and had to bring in bottled water because the water fountains weren’t certified safe. While the bays are safer now, they retain a gritty, industrial look, with plenty of room now that the summer programs have grown to about 150 students.

Computer science was a natural choice for the new space, because the Mountaintop C acquisition came at a time when Lehigh and many other institutions were rapidly expanding their computer science programs. Lehigh’s Data X initiative, which Lopresti leads, emphasizes cross-disciplinary pursuits, so a project might have elements of data analysis, business, bioengineering, or even journalism.

A Silicon Valley Style

In renovating Mountaintop C’s office space, Lehigh President John Simon drew on past experiences as a faculty member and department head, not all of which were successful. He tells the story of planning for a new science building at Duke University that he had hoped would foster interaction and collaboration among chemistry and biology faculty and students by dispersing them in the same building. The problem was that the department faculty ended up segregated in their own pods.

“Some of the reason for the outcome is that department chairs did all of the programming,” says Simon. “You cannot assume that if you simply mix faculty from different departments that interdisciplinarity will happen. In the end, we encouraged incremental change, rather than achieving a new level of interdisciplinary activity. It didn’t produce real culture change in the institution. It was still too easy to hide. You didn’t have to interact with any of your colleagues.

“The lessons learned, in my view, were that you need visible open space to encourage this interdisciplinarity and collaboration, and it requires strong leadership from the top,” says Simon. “I can’t overstate that.”

Using lessons learned from that experience, the university turned the building’s next iteration into a glass-filled, open, well-lit space that encouraged people to interact and work together. This, combined with strong leadership support for interdisciplinary work, made for a much more successful space.

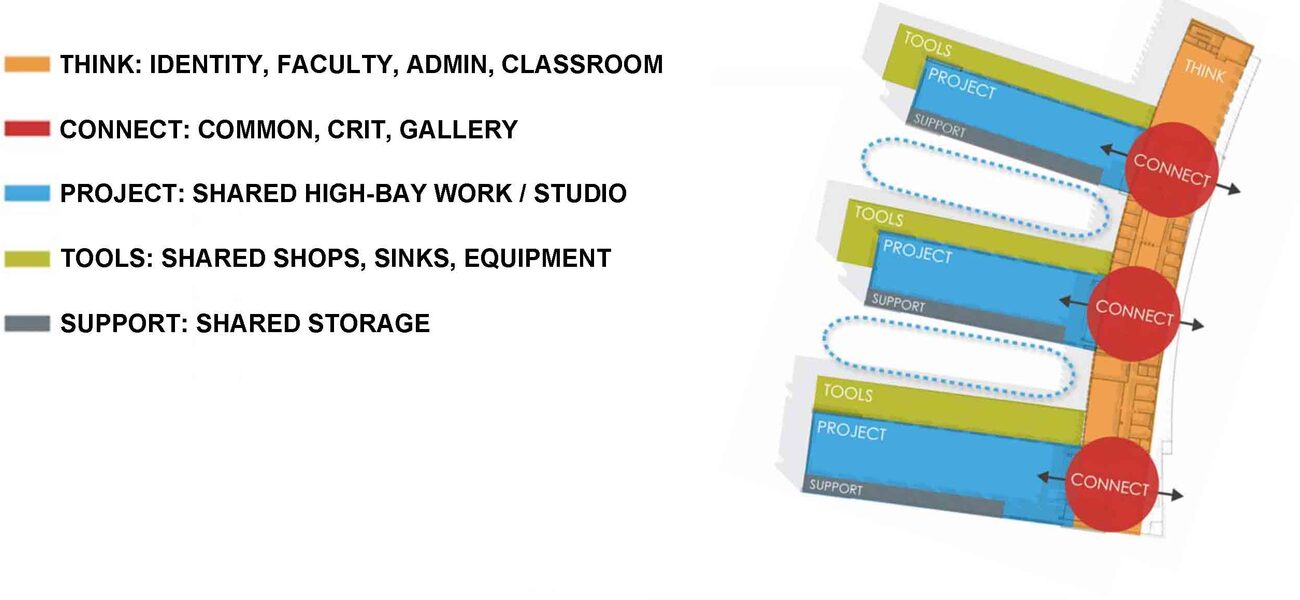

The Lehigh team worked with EYP architects to turn the curved three-story office section of Mountaintop C into a set of spaces that encourages collaboration, communication, and up-to-date education. The “Crescent” renovation involved ripping out a central corridor to open up the space and incorporating conference rooms of varying sizes, similar to modern high-tech office floors. “I very much was driven by this notion of Google and Facebook and what I was seeing in Silicon Valley and other places,” says Lopresti. “We are training students to work at these kinds of places. I want our academic building, Building C, to have that look, too.”

High-tech features include a reservation touchpad, so faculty and students reserve meeting rooms in real time. “All of the rooms have technology in them. They have large screens. They have videoconferencing. They have tables that are writable. Some of them also have walls that are painted with whiteboard paint,” says Lopresti.

The spaces where the high bays intersect with the crescent got special attention, with an emphasis on visibility and interaction through “mixing box” spaces that overhang about 20 feet into the bays. A telepresence classroom helps Lehigh students connect with other parts of campus and other institutions around the world. The exterior was transformed with glass to invite in natural light. At the same time, the renovation preserved the solid industrial feeling of the interior without trying to add elegance. “It is a space where students feel they can do whatever comes to their mind and the space appears indestructible; your building manager isn’t sitting there worried about the wide range of activities in the space,” says Simon.

Tensions and Results

As might be expected, many faculty were not fully on board with the idea of giving up allocated spaces to interdisciplinary goals. “What if you push people to be in space that they don’t necessarily choose to be in?” asks Simon. “What if you make the decision at the top of the university to put people in locations because it is in the best interest of the mission and purpose of the university, not necessarily in the perceived interest of a department or individual faculty members?”

His answer involves strong leadership aligned toward an institution-wide goal, as well as engaging faculty as standard-bearers for change. “When you really want to erode culture, I think the president and provost have to be aligned and both have to be willing to get up there and say, ‘This is where the institution is going, and this is why we are doing this,’” he says. “You might have to decide that in an unconventional way. It is not necessarily, ‘who are your best-funded faculty’ anymore. It is, ‘who are thinking the most about delivering on the mission of the academic institution looking forward?’”

While faculty members are still sorting out those tensions, students are diving into the space and thriving. “The kids just gravitate to this. They love this kind of space,” says Simon, citing a couple of student projects in particular: a hyperloop pod built to enter in a challenge sponsored by Elon Musk, and a group of students testing different building designs for communities in West Africa to improve ventilation within a building while preventing malaria-bearing mosquitoes from getting in. With new data showing many students value experiences over specific faculty relationships in their education, he’s enthusiastic about having a space that provides these unique opportunities.

While some might think about renovating the high bays into multi-story classrooms or offices, Lehigh is keeping them just the way they are. “Never did I hear a suggestion that we convert it into a traditional space. No one ever really considered that seriously,” says Lopresti. Some issues remain; for instance, 150 students in a high bay during the Mountaintop Experience can get very loud, and the 60-foot ceilings pose a challenge for heating and air conditioning.

Still, they do have uses beyond student experimentation. “We use them for hackathons, we use them for receptions,” he says. And then there’s the fun factor. “This would be a great place to fly drones around in!” says Lopresti, before admitting, “I have done that.”

By Patricia Washburn