Because it’s expensive to heat and cool outdoor air drawn into a building, workspaces tend to be ventilated only enough to meet ASHRAE minimums or achieve a LEED credit. But air quality profoundly affects workers’ cognitive performance, and even modest increases in ventilation can yield productivity and health benefits that far exceed the cost, says Joseph Allen, assistant professor and director of the Healthy Buildings Program at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Any company still citing sustainability as a justification for skimping on ventilation would do well to expand its definition of sustainability to encompass human health and wellbeing, he says.

“ASHRAE 62.1 is the Standard for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality, and they use the word ‘acceptable’ for a reason,” says Allen. “It’s not the standard for healthy or optimal indoor air quality; it’s just the minimum level of ventilation that will allow you to walk into a space and not object to the odor. That’s the standard by which we’re ventilating all of our spaces. But 30 years of public health literature show that there are lots of benefits in going above this minimum ventilation standard.”

The benefits that are of most interest to companies, of course, are financial. “Healthcare costs are 25 to 30 percent of employee salaries,” says Eileen McNeely, co-director of SHINE (Sustainability and Health Initiative for NetPositive Enterprise), another program at the Center for Health and the Global Environment. “But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. There’s a lot more behind that in terms of how employees engage and perform at work, and what that means to business operations.” McNeely and Allen are exploring ways to shift the conversation from the negative metrics of healthcare costs, disease, and disability to a business approach that focuses on employee wellbeing and engagement.

In short, says McNeely, for a business model to be truly sustainable, it must encompass human wellbeing. “It is necessary to have thriving individuals if you are going to save the planet,” she says. “So we try to embed that directly into the business model. But if we’re going to embed it, we need a metric to measure it.”

Get HaPI

To that end, SHINE began developing the Health and Performance Index (HaPI) in 2014, in partnership with Johnson & Johnson. A new metric was sorely needed, says Leigh Stringer, workplace strategist with EYP Architecture and Engineering and author of the books The Green Workplace and The Healthy Workplace.

“It’s kind of the Wild West out there in terms of health metrics,” says Stringer. “In researching The Healthy Workplace, I asked companies how they defined health and wellness, how they defined success, and how they measured these variables. The traditional view is to define health and wellness in terms of reducing health insurance costs, and success in terms of worker productivity. But the leading-edge organizations I talked to were focusing less on costs and more on understanding the human body and mind.

“They define success in terms of employee engagement, getting them excited about their jobs and not just productive,” says Stringer. “Instead of measuring productivity in cost per square foot, per seat, or per person, they’re measuring it in engagement, retention, and corporate culture and community. These are the things that make people healthy and productive, and make them want to stay.”

But within companies, Stringer found that different departments were approaching these measurements differently. A real estate executive or a facilities manager might focus on a LEED rating or WELL certification, while a chief medical officer or chief wellness officer might focus on awards from the Wellness Council of America or the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, based on reducing smoking and improving employee health outcomes. Meanwhile, a human resources manager or executive might measure success in terms of engagement, satisfaction, and culture. “At the end of the day, all these things are kind of supporting human performance, but none of them talk to each other,” says Stringer.

The HaPI encompasses four components: wellbeing, which includes both mood and life satisfaction; productivity; engagement; and workplace culture. Stringer has been collaborating with McNeely on the portions of the HaPI related to the built environment, and her firm, EYP, has been testing questions related to performance, engagement, culture, health, the built environment, and the interactions of these factors.

Ventilation Pays Off

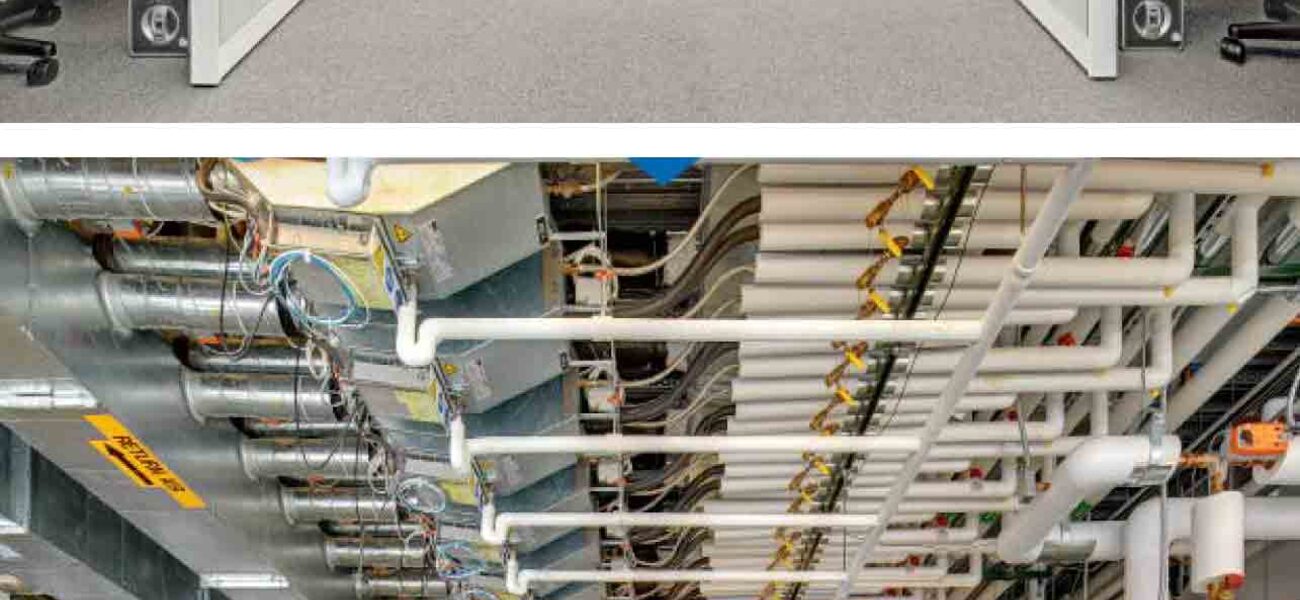

Allen has been exploring the health impacts of specific design factors such as noise, lighting, layout, density, materials, off-gassing, and systems affecting air quality, temperature, and humidity. A research group he created at Harvard, called Sensors for Health, is using wearables and sensors to track workers’ chemical and environmental exposures and precisely assess a building’s health performance in real time. Utilizing these new tools, his team recently conducted a series of research studies that are revealing the outsize cognitive benefits of fresh air.

In the first of these studies, led by Allen and conducted in six workdays over the course of two weeks at the Syracuse Center of Excellence, a subject pool of 24 knowledge workers performed their computer-centric jobs in a room specially equipped to expose them to precisely calibrated ventilation conditions. Neither the subjects nor the experimenters knew which conditions were being tested on any particular day, so the test was truly double-blind, a rare feat in public health circles. Three variables were tweaked—ventilation, carbon dioxide, and volatile organic compounds—and the workers’ cognitive functioning was assessed via a standardized test each day at the same time.

The results were striking. “When people spent time in the optimized indoor environment, their cognitive-function scores were double what they were in a conventional or underperforming space, across nine cognitive-function domains,” says Allen. “The three domains in which we saw the biggest improvements were crisis response, information usage, and strategy—areas that in previous studies have been most closely linked with productivity and salary.”

A particularly shocking finding was the effect of carbon dioxide—independent of ventilation—upon cognitive function. (Since the variables of ventilation and carbon dioxide are usually tightly linked, the researchers injected carbon dioxide into the air supply to achieve the desired concentrations.) Cognitive function was tested at three carbon dioxide concentrations: 500 parts per million (ppm), typical of outdoor air; 1,000 ppm, the level typical in buildings conforming to ASHRAE 62.1; and 1,500 ppm, a level commonly seen in schools sampled across the U.S. Significantly lower scores were seen at just 1,000 ppm.

“For 100 years or longer, we have thought carbon dioxide was benign at these concentrations,” Allen points out. “The occupational exposure limits start at 5,000 parts per million, but we see effects at the level that our ventilation standard is telling us we should design buildings to.”

One crucial takeaway from this and subsequent studies Allen’s group has performed is that optimal ventilation offers vast payoffs in employee productivity and wellbeing. “With even minor improvements to buildings and spaces, we can see a dramatic impact right away on performance,” says Allen. “When we modeled the costs of doubling ventilation rates in the space, we found that they were on the order of $20 or $30 per person per year, but the benefits are on the order of $6,000 to $7,000 per person per year, not even accounting for the co-benefits of reductions in absenteeism.”

And those won’t be the only payoffs. “Owners who don’t improve air quality will be hearing about it soon enough from building occupants,” says Allen. “They’ll be monitoring formaldehyde and benzene and carbon dioxide with sensors plugged into their mobile phones. Everyone’s going to have access to this information. In the knowledge economy, you can’t hide.”

Deborah Kreuze

Additional Resources:

- Healthy Buildings Program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

- COGfx

- Joseph G. Allen, Piers MacNaughton, Usha Satish, Suresh Santanam, Jose Vallarino, and John D. Spengler, “Associations of Cognitive Function Scores with Carbon Dioxide, Ventilation, and Volatile Organic Compound Exposures in Office Workers: A Controlled Exposure Study of Green and Conventional Office Environments,” Environmental Health Perspectives 124:6 (June 2016), DOI:10.1289/ehp.1510037. http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/15-10037/

- Leigh Stringer, The Healthy Workplace: How to Improve the Well-Being of Your Employees—and Boost Your Company's Bottom Line. New York: American Management Association, 2016.

- Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador, eds., Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. New York: Wiley, 2008.

- Biophilic Design