London’s King’s College has tapped building information systems and financial data to maximize the use of space while reducing energy costs and carbon emissions by employing three strategies: leveraging shareable and flexible space, challenging assumptions about the need for individual offices, and having leaders set progressive examples for other staff. Efficiently planned and utilized spaces are inextricably linked with sustainability for growing academic institutions like King’s College, especially when the cost of property is expensive, according to architect and planner Ian Caldwell. As the university’s director of estates and facilities, Caldwell oversaw a number of redevelopment projects at its Strand campus that offer valuable lessons for environments facing similar challenges.

Founded in 1829, King’s College is among the world’s best-regarded universities, hosting 26,000 graduate and postgraduate students from 140 countries. The Strand campus, in central London, features a wide variety of architectural styles, and houses the college’s faculties of arts and humanities, natural and mathematical sciences, and social sciences and public policy. The 570,000-nsf internal area of campus is slated for expansion to accommodate an additional 3,000 students by 2020. “We are expanding,” says Caldwell. “Space requirements are on a growth trajectory, which sets a real challenge in the center of London.” Getting optimal value for the university’s money is a core concern, as is reducing the campus’s carbon footprint.

Beginning in 2002, space and quality concerns led to the redevelopment of three buildings: the original 1830s stone building on campus, a late-20th-century one constructed of concrete, and the acquisition of a 1770s-era building adjacent to the campus. “This was when sustainability was becoming a major watchword,” says Caldwell. Alongside more traditional activities such as procurement, asset sharing, and working practice evaluation, building in sustainability became a key part of improving space utilization.

The redesign of the original 1830s building—transforming dark corridors into daylit spaces with glass office walls—was well-received by faculty and students. Following this, the redesign of the concrete Strand Building included improved cross-ventilation, chilled beams, glass walls for offices, and central open floorplates. The upper three floors had previously been chemistry laboratories, with floor-to-ceiling heights that were ideal for the desired type of flexible office layout. The redesign places offices on the building’s perimeter, surrounding large, open social and working spaces in the center. Furniture is adjusted to suit departmental requirements. “We are continually moving people around the campus, so this arrangement is ideal,” he says. “There was some initial resistance, but eventually the faculty began to appreciate a more open environment that was not just long corridors of shut doors.”

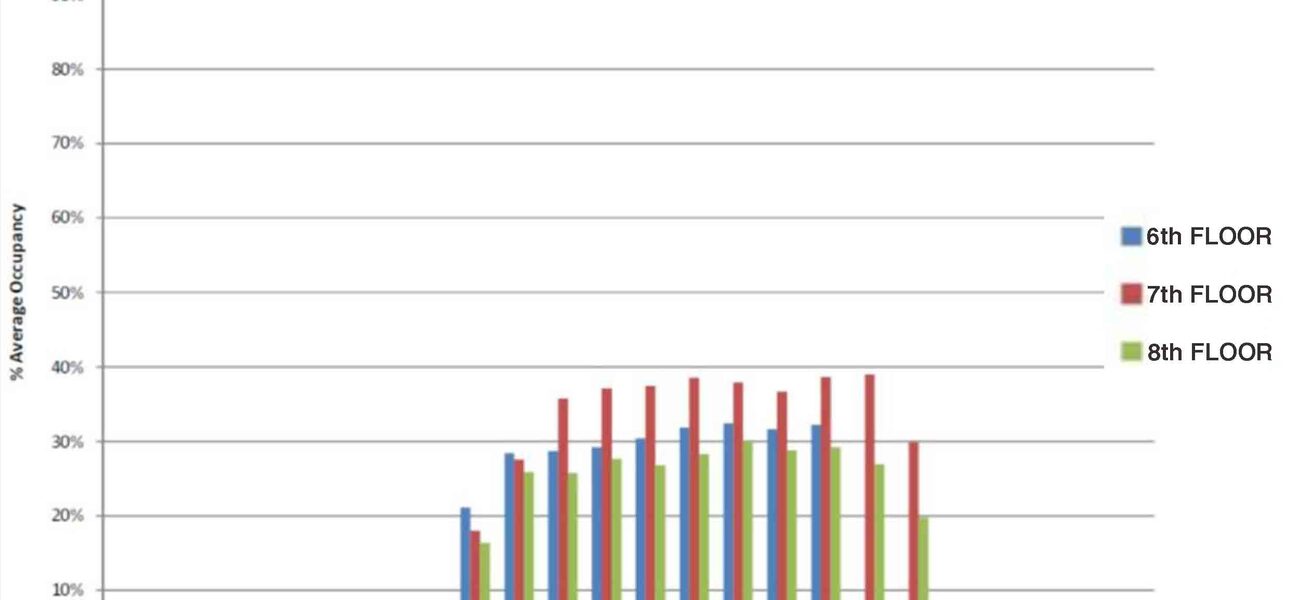

This more open-plan approach is supported by reams of building management data. Collected via sensors, the system links temperature and lighting information to occupancy; when offices or spaces are not in use, lights are dimmed and the temperature is allowed to baseline. “Using building information data on energy use, we can see where nodes of activity are located,” says Caldwell. “Among the lessons learned was that the academics who insisted on private office spaces weren’t necessarily using them,” he says. “This is a discussion we are now having, because clearly if offices are only occupied one day a week, that is not an acceptable use of our available space,” says Caldwell. The system isn’t perfect—in larger areas designed to accommodate eight or 10 people, the building information system can’t track their individual energy consumption. “We are looking at whether we can use technology such as workstation or Internet connectivity to supplement the energy data,” says Caldwell. Other research involves benchmarking the use of space at comparable institutions, in particular for discrepancies in the utilization of teaching rooms. “As with many universities, the last term of summer is when that drops very low,” says Caldwell.

Redevelopment of the east wing of the 18th-century Somerset House presented similar lessons. “It is not the sort of building that you can just carve up into single offices,” says Caldwell, “so staff had to work with the idea of shared units, which is a very sustainable solution.” Space planners had to work closely with faculty and do some “social engineering,” allowing individuals to choose their officemates. Initially, occupants subdivided the shared spaces by using tall bookcases as room partitions, but now, according to Caldwell, those bookcase heights are coming down. “They have realized that the quality of working space can be improved by having shorter furniture,” he says. Provision of cordless phones for the building proved popular as well. “If someone has a private phone call, they can go into another room and take the phone with them.” Related worries, such as the concern that materials from private libraries would be liable to go missing if kept in a common area, can be solved with locked bookcases.

Leadership for such changes to the principle of “an office for everyone” is critical. For the 22 Kingsway building, a 71,000-sf, brick office block that the College acquired to accommodate rapid enrollment growth, Caldwell and his team were under pressure to forego their preferred methods for efficient space planning. “Our academics have clout, and at the time, we had to move fast to occupy the new building,” says Caldwell. Instead of the open-plan, shared spaces preferred for the historic Strand and Somerset House buildings, offices at 22 Kingsway remained largely compartmentalized. “It cost us $23 million, and we got fewer people into the building,” says Caldwell. However, the new vice president, who had just come on board when the 22 Kingsway redevelopment began, has set a new standard: She herself works in an open-plan office with her staff, and books meeting spaces via the centralized booking system used by all faculty. “It’s a way of demonstrating that it isn’t a slight to share space; it’s actually more collaborative, as well as more efficient.”

Explicitly linking the cost of space to a department’s budget has been key in encouraging the attitudinal change that the campus needs from staff to meet its sustainability goals. “Faculty are actually keen to understand the use of space when they learn how it affects their bottom line,” says Caldwell. Previously, space had been accounted for at a high level that did not filter down to the individual departments. Now, that financial data is transparent for departmental decision-makers, and the choices they are making reflect that. “If they can shrink the amount of space they need or use it more efficiently, they will benefit financially, because space is in their budgets,” says Caldwell. By linking the sustainability and space strategies, Caldwell helps make faculty aware of ongoing costs, as well, such as those associated with utilities, maintenance, and equipment. “A filing cabinet may cost only $200 to buy, but it costs more than that per annum in terms of the space it takes up that could be used more efficiently for other things.”

Keeping data transparent in an academic environment works wonders, according to Caldwell. “Academics are used to working with data, particularly if they have given it to you in the first place,” he says. Paired with controls for lighting and temperature, a compelling argument can be made for incremental, progressive changes in the way faculty and students use space and energy. Reconciliation of staff and student numbers with tighter space allowances, a shift to shared academic offices and common teaching rooms, and the endorsement of more egalitarian thinking about “who gets what” by leaders who practice what they preach all contribute to cost and sustainability savings. Setbacks, such as those encountered with the 22 Kingsway building, serve as opportunities to learn how academics use their space and feed this into the college’s future projects. For his academic and architecture colleagues, Caldwell has one final piece of advice: “Build as few walls as possible.”

By Liz Batchelder

This report is based on a presentation Caldwell gave at Tradeline’s Space Strategies 2014 conference.