The University of Washington’s new multi-species vivarium and animal program consolidation overcomes the challenges of combining two distinct research facilities and achieves goals of flexibility, efficient operating procedures, improved animal and personnel welfare, and a sustainable financial model—thanks to the early involvement of all affected parties, detailed team-based planning, and mockups.

The 83,000-sf animal facility, under construction at the UW, is a joint venture between the University’s School of Medicine and the Washington National Primate Research Center (WaNPRC). Within the UW School of Medicine, the Department of Comparative Medicine (DCM) has been instrumental in the building’s design and will, in collaboration with the WaNPRC, be responsible for its operation. The underground facility combines shared functions, such as cage wash, while still maintaining two separate operations, and is designed to house a population that is one-third rodent, one-third large animals, and one-third non-human primates (NHPs).

“It’s almost like taking two different universities and having them share a building,” explains Lesley Colby, senior director of animal resources and operations at DCM.

WaNPRC is associated with UW but funded largely by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The DCM is an academic department and provides animal care and ancillary services like pathology for University researchers. The two entities evolved separately, and the programs had some crossover but not much, says Colby. When the University undertook a campus-wide planning project, it concluded that creating a shared animal use facility made sense.

“Animal research was spread all over our main and auxiliary campuses, and for financial, facility, and regulatory reasons, that was not good. Everyone needed more space, so it made sense to put both entities in one centralized facility that would accommodate various species—and species’ needs that are changing and will change over time.

“Flexibility was one of the primary driving forces behind the building design.”

Developing a Plan

Building one facility to house multiple animal groups offered UW financial and operational efficiency, but required more flexibility for room features and large equipment to support the combined set of animal models and ever-changing scientific/research needs.

Besides the need to centralize and address its aging facilities and make them more cost-efficient, UW’s new vivarium needed to address:

- Increased sophistication and intensity of animal-based research.

- Increased collaborative science and technology.

- Rapid scientific evolution.

- Renewed interest in large-animal models.

“We’d love to have every room be 100 percent flexible, but each species has unique requirements and equipment, plus we have limited funds,” notes Colby. “We knew we wanted facilities built to house animals instead of vice-versa—trying to find space suitable for the animals.”

Since science is trending toward a renewed interest in large-animal research, because in select situations it’s more applicable and easier to translate to humans, it’s unlikely UW would ever need 100 percent rodent space, says Colby. That was one planning consideration.

Procedure space is also more in demand for various reasons, she notes. In the past, research facilities had few procedure rooms; the majority of the space was animal housing. Now, researchers and institutions want everything in one controlled space for better biosecurity, to safeguard animal welfare and to minimize research variables. Today’s research involves more, larger, and more expensive equipment, as well.

“We have larger equipment and procedure space in a much higher proportion than in the past; we’re finding it is cost-efficient to plan facilities this way. Mostly, we need more space to accommodate electronics.”

Installing WiFi and plenty of electrical connections can be challenging, especially when the connections must run through rooms that need to remain contamination-free. “We have had to do some special modifications to run cabling through rooms because of required parameters.”

Biosafety requirements change over time and there’s no way to know exactly what’s ahead, says Colby, but the UW team tried to anticipate future needs in that regard and in other areas.

The vivarium’s design includes bench work and counter space, but more often small housing or procedure space with finely controlled environmental conditions is needed, so the design includes two rodent behavioral testing suites and two rodent cubicle suites, clusters of small rooms where environmental conditions can easily be changed.

Behavioral research is becoming popular, she says, but requires space for items such as mazes. Even 20 cages of rodents need a large space—such as multiple 8-by-10-foot cubicles—but that space must also include small, controlled spaces, so UW designed rooms specific to those needs.

The design includes spaces specific to hazardous containment and animal imaging. “One complicating factor with the imaging equipment is that we have animals coming from all over campus, so to minimize contamination in imaging, we had to position it so it posed the least possible risk to other animals in the facility.”

The Design Details

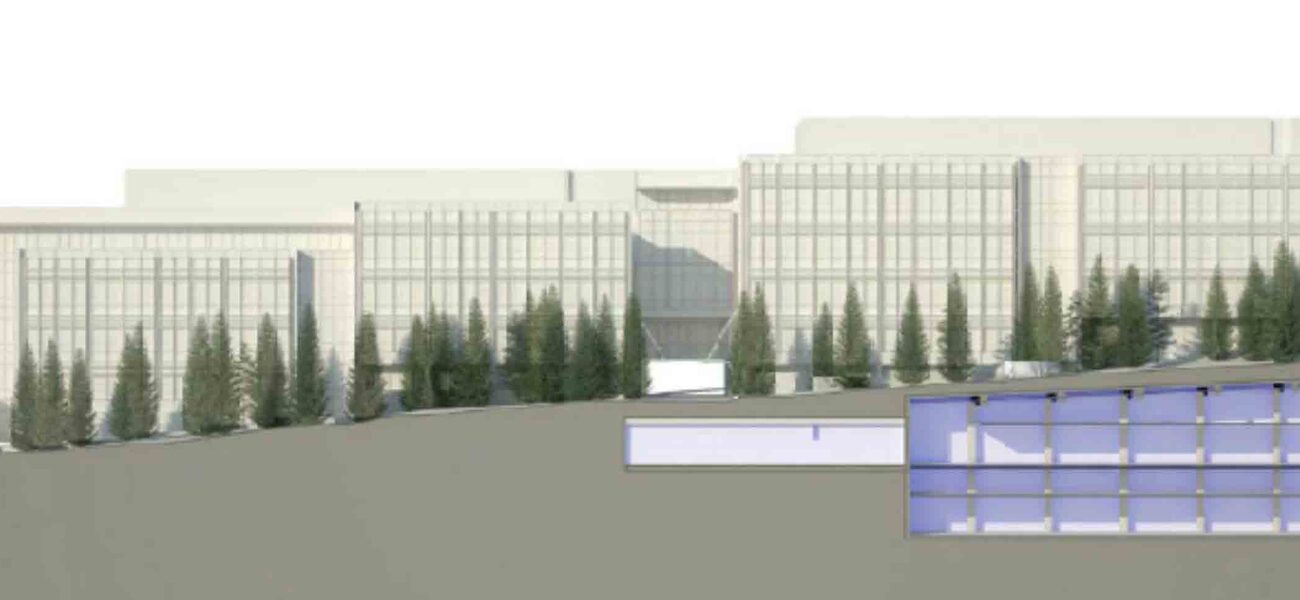

UW’s two-story, $124 million vivarium is scheduled for completion in 2017. The facility is being built underground to comply with local zoning laws that prohibit disrupting the scenic vistas above ground.

The first floor has space for 10,000 cages and contains a mixture of holding and procedure rooms, a small animal imaging suite, a transgenic rodent suite, and behavior and cubicle suites, as well as storage, locker rooms, and office space. Testing/behavior suites and cubicle suites can each serve as housing and/or procedure space; in the planned rodent standard areas, there is a ratio of two housing rooms per one procedure room.

The second floor will house nonhuman primates on one side and large animals on the other, with surgery suites, necropsy rooms, and animal imaging rooms in between. The ratio of housing to procedure rooms there is basically 1:1, with the procedure rooms set up as anterooms to the housing rooms; researchers must walk through procedure rooms to access housing.

The second floor also will house the shared cage wash area. Because they will have at least 10,000 rodent cages, a tunnel washer will be more cost-efficient, says Colby, although the facility also will have a few rack washers for larger animal cages.

Putting the facility underground presented an opportunity to knock down a wall and connect to an existing 10,000-rodent-cage facility, adds Colby, so the old and new vivariums can operate as one.

“If we get filled to capacity, we would actually need two tunnel washers, but we are only building one for now,” she adds.

There were some concerns about NHP caging being in a shared cage wash area, mainly because select NHPs carry a virus that doesn’t affect them but can be harmful to humans, says Colby. Personnel were initially concerned about cross contamination in the cage wash area. It took a while, but once everyone involved thoroughly examined the situation and realized that the personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by all cage wash personnel would be effective, everyone got on board with the idea of a shared cage wash, she adds.

Because cage wash equipment is expensive, the group figured out a way to safely share one cage wash room run by one staff. Cages will be marked and tracked electronically, so the cages from NHP, large animals, and rodents can be tracked for billing.

Other Considerations

In Seattle, where space is at a premium, it’s common to build under the water table, says Colby, but it adds another dimension to a project. UW’s vivarium is one floor below the water table, and building it involved digging a huge hole and basically creating a “tub” with a waterproof membrane.

Water will be diverted constantly with systems like internal gutters and dewatering wells, and the walls are concrete slabs about 4 feet thick. The waterproofing does not rely on one system but contains redundancies to avoid problems if a system goes down, she adds.

There are actually four layers to the building: two occupied levels with two alternating interstitial spaces. This design allows much of the room/building maintenance activities to go on without building engineers, repair personnel, and vendors needing to enter the animal-occupied areas. It also makes it easier to do renovations and run wires and place new equipment without disturbing animals or personnel.

“From the users’ perspective, it is also nice to get some of the large pieces of equipment out of our work space—less to clean and to work around.”

The UW project pays careful attention to personnel enrichment, explains Colby. Animal welfare is always the number one priority, and preserving research is a close second, but UW’s project team recognized the importance of keeping personnel happy, especially with the building being windowless and underground.

Light tubes are being installed in areas where natural light is permitted, such as stairways, the main lobby, and parts of the break room. “The only place we can have natural light is where only humans will be.”

The shared conference rooms/break rooms are designed with movable walls and are divided into three distinct areas that can be used for training and meetings, as well as food breaks; computers are provided for checking email during breaks. Warm, inviting colors and fabrics were chosen for the furniture and décor.

Various finishes will be used to brighten the vivarium’s atmosphere, as well as inform: different floor colorings to indicate each area’s designated use; pixie lights at the end of corridors to break up the monotony and serve as guides; door frames in different colors depending upon where they lead; and realistic faux wood accents, to give break rooms and animal rooms a less institutional feel. Internal hallways within the vivarium that are as long as 90 feet will be decorated with murals that can be easily changed.

“To keep staff happy and healthy, it’s important to budget extra time and money for creative adornment of the work environment,” advises Colby.

UW also went an extra step to secure multi-year service agreements on equipment, especially since Seattle’s geographically isolated location can make it difficult to get equipment delivered and serviced. Such agreements are usually for a year, but facilities often need at least a year of using the equipment to discover any issues, she says.

Seattle is very environmentally conscious as well, so UW is trying to achieve LEED certification with the building design.

Making it All Come Together

UW made a concerted effort to involve the animal care people from the beginning of the planning efforts.

“We want to make sure we’re collaborative; we actually had a mandate that we be involved and attend all meetings and workshops. I think everyone involved has been very happy with this arrangement,” says Colby.

UW extended the collaborative effort to the public, keeping people informed through periodic town hall meetings that anyone could attend.

Creating mockups of the spaces has helped everyone see firsthand how the architects’ vision translates to real life. A room size that looked good on paper ended up being too small, for example.

UW also involved the commissioning agent early on. Typically, the agent inspects a facility after completion to check and sign off that work was done properly. But UW thought it better to take advantage of the agent’s experience to fix problems before or as they occurred.

“The agent can see what’s happening as it happens, and also has prior knowledge of what works and what doesn’t,” explains Colby. “They bring the experiences of past projects, so we don’t make the same mistakes.

“We have found early involvement to be very beneficial.”

By Taitia Shelow

This report is based on Colby’s presentation at Tradeline’s Animal Research Facilities 2014 conference.

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

ZGF Architects LLP

|

Architect of Record

|

|

Flad Architects

|

Vivarium Architects

|

|

Skanska

|

General Contractor/Construction Manager

|

|

Affiliated Engineers, Inc. (AEI)

|

MEP Design Engineers

|

|

KPFF Consulting Engineers

|

Civil & Structural Design Engineers

|

|

Xigma

|

Loading Dock and Cage Wash Process Engineer

|

|

Vibro-Acoustics Consultants

|

Vibration and Acoustic Designer Consultants

|

|

Hart Crowser

|

Geotechnical Designers

|

|

CPP, Inc.

|

Wind Tunnel and Dispersion Model Analysts

|

|

Morrison Hershfield

|

Building Envelope Consultant

|

|

Lerch Bates

|

Elevator Consultant

|

|

MacDonald-Miller

|

Mechanical Contractor Construction Manager

|

|

Cochrane Electric

|

Electrical Contractor Construction Manager

|

|

Wilson Jones Commissioning

|

Commissioning Authority/Agent

|

|

RDH Building Science

|

Building Envelope Commissioning Authority

|

|

GeoEngineers

|

Contaminated Water and Soils Environmental Engineers

|

|

Broaddus & Associates

|

BIM-FM/COBie consultants

|