The key to fully leveraging a building automation system (BAS) in animal research facilities is to put all of the information about the animals’ environment at staff’s literal fingertips with tablet computing. Additionally, a few simple upgrades—some derived from unlikely sources—can help reduce costs associated with controlling two of the industry’s primary concerns: ammonia detection and airflow. Information technology advances like these show tremendous promise for animal research facilities looking to save labor hours, says Paul Fuson, national sales manager for the life science business at Siemens Building Technologies for Infrastructure and Cities.

“There is a lot of information required to keep the animals from becoming distressed and thereby unavailable for research,” says Fuson. “For instance, if the temperature or the humidity gets too high, obviously mammals are likely to sweat or pant, so ventilation is one important issue.” Lighting often also needs monitoring, most importantly in behavioral studies where animals’ circadian rhythms must be controlled. Additionally, “Many labs use pressurization as the first barrier to prevent infections from spreading,” he says.

The Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) audits animal facilities for their overall performance by focusing on whether the animals have been comfortable over the long term. Labs provide documentation that shows extreme highs and lows in data points, but auditors are primarily concerned with averages, which is not particularly helpful to staff responsible for the day-to-day welfare of laboratory animals. Most BAS systems can generate these reports, but their primary benefit is in detecting when a factor is still in the process of becoming dangerously high or low. “You need an alarm to get those things handled ASAP,” says Fuson. “It’s less about monitoring the things required by law and more about making sure the research isn’t disrupted.”

Increasingly, lab technicians are able to access a wide variety of information about their vivariums using tablet software for both Apple and Android devices. “The key thing is that nobody is going backwards with this technology,” says Fuson. “Everybody is asking for information faster and sooner, and for ways to evaluate the impact of that information.” This can be accomplished with smart mobile devices connected by Wi-Fi, or via wall-mounted tablets at appropriate spots throughout a facility. “Some universities go with mounting the tablets because they are concerned about losing them,” says Fuson. “It’s ironic, because the expense of installing the devices everywhere they are needed might be more than letting staff carry them around. But it’s conceivable that in a year or two, there will be other uses for the tablets, so it may become more cost-effective to get one for everyone. It’s really a matter of convenience.”

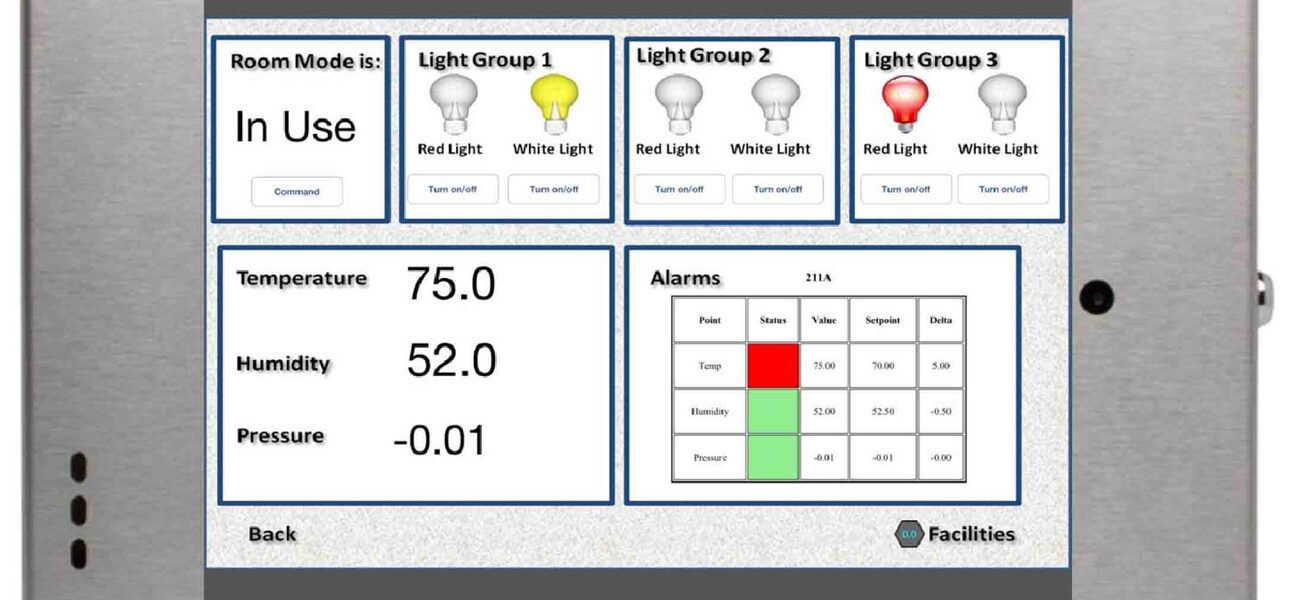

Siemens’s software, Facility Prime™, was initially developed for iPads. Fully customizable down to the look and feel of its user interface (UI), Facility Prime represents a sea change in the way that lab technicians monitor thousands of animals. From a smartphone or tablet, staff can check on variables that range from air change rate to temperature to lighting levels, as well as turning automation on and off if values indicate that a system needs repair, adjustment, or rebooting. The simplicity of the UI, which typically uses color to indicate problem areas, means that a quick scan of critical elements can reveal problems.

“For example, if animal statuses all have values within acceptable levels, you would see all green squares. But if a pressure or temperature value is significantly different than its set point, you would see a red square indicating that that system or room or cage rack needs attention,” says Fuson. Additionally, the reports the software generates can be tailored to individual users’ needs. “You can request that a report doesn’t show all of the rooms, or shows only areas where there is cause for concern.”

Twenty years ago, the only place such information was available was at the workstation for the building operator, which sometimes was in a different building from the vivarium. Moving the workstations to halls near lab technicians was an improvement, but created clutter. “The goal has always been to get the right information at the right place and the right time,” says Fuson. “We now have devices that are inconspicuous, but that are much more useful than they ever were before.”

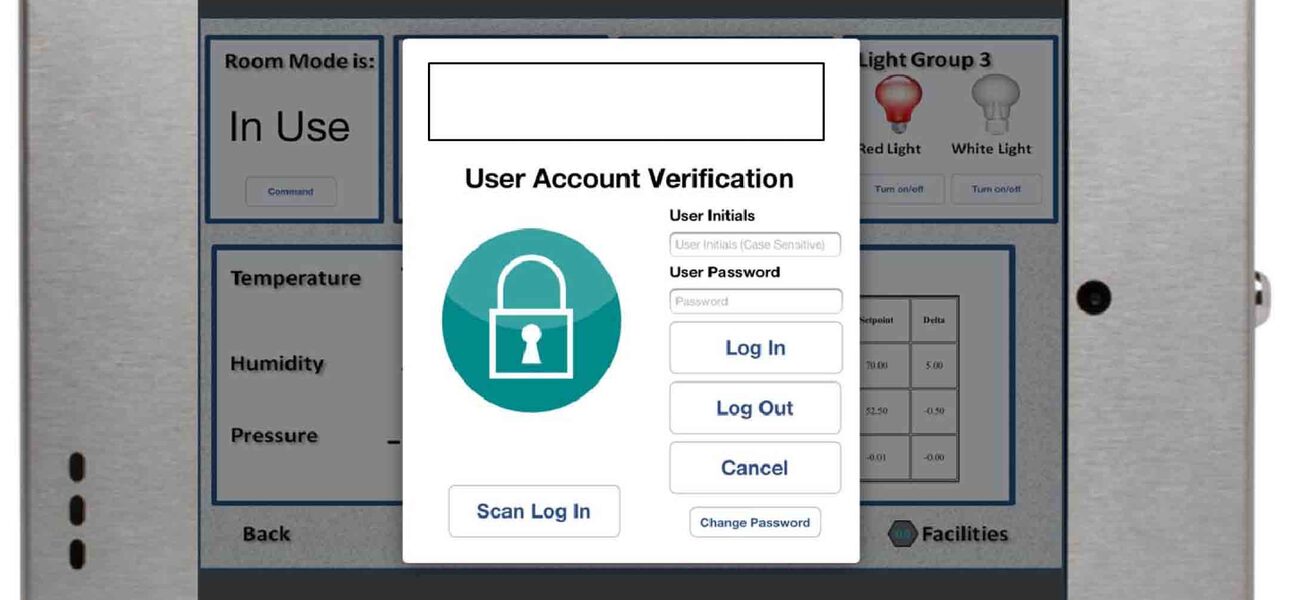

Facility Prime can be modified to require user authentication or dual login for security, and users can be assigned different levels of access and privilege. A technician may have the ability to view all of the systems, but not necessarily to make any changes. “The idea of putting in security is the real heavy lifting in the BAS world,” says Fuson. “It is one of those things that can’t be done overnight.” It also requires a thorough consideration of the good manufacturing practices and good lab practices mandated by the FDA, he says. “You want to try to anticipate not just what your structure is today, but how it might evolve, and how you want to control access. For example, you might want to make it so that a second authorized person is required to change the ventilation or the lighting in a space.” Authentication can be done by a simple login or by a finger- or thumbprint.

Other technical considerations for animal facilities include reliable Wi-Fi accessibility. “There are a lot of metal structures in a vivarium,” says Fuson. “Wireless is great, but it may require some effort to make sure it is available everywhere you need it. It would be terrible to have a brand new facility or to have spent a lot on retrofitting, and then to have tablets that can’t connect to the network.” Whether to have the software and the data it collects on a local server, rather than Cloud-hosted, is another issue that organizations should debate. With a Cloud solution, says Fuson, “You are paying for knowing that your data is secure, but you are also paying for an application that may be just too big and powerful to be supported by your organization all by itself.”

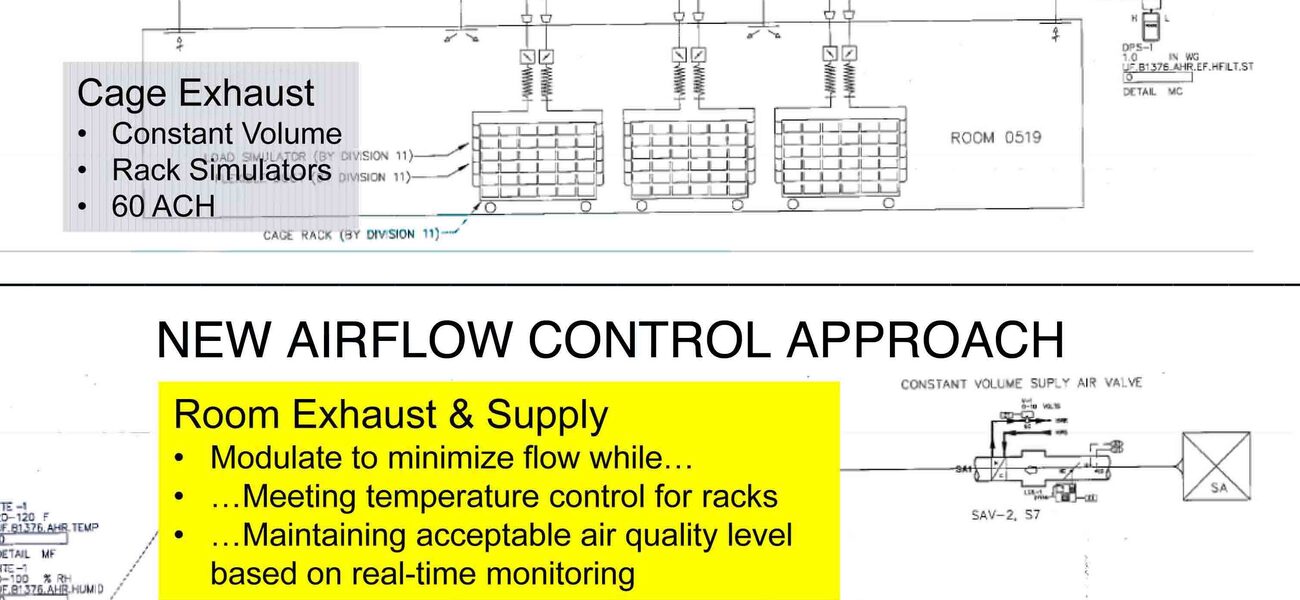

To help subsidize the costs of Facility Prime and the devices to run it, Fuson suggests some novel approaches to energy cost savings associated with ventilation. “The National Institutes of Health’s energy bills reflect that 44 percent of their cost goes into ventilation—actual fans moving the air around,” he says. “Another 22 percent of the bill goes into cooling. So right there, for a large organization, two-thirds of their energy bills have something to do with pushing air into the rooms and sucking it out.” Some improvements Siemens has implemented with another client include an indexing system for animal-occupied cages. “If at a given time there are not a lot of cage racks in a room, you don’t need as much cooling. The thermal load is not as great.” Installing airflow sensors along with more energy-efficient exhaust terminals, fume hoods, and air valves (such as those made by Venturi) can likewise assist with real-time monitoring and cost savings.

Ammonia, a critical factor in overall air quality in a vivarium, has historically been very difficult to monitor. Absorptive infrared detector technology can sense low concentrations of specific chemicals but requires periodic recalibration and element replacement after two years. Photo-ionization detectors ionize the electrons away from gases to detect any substance other than oxygen and nitrogen in the airstream. They can sense very low concentrations but also require regular replacement of sensing elements. A third technology, photo-acoustic infrared, pulses the sample with infrared light and “listens” for the high-frequency noises characteristic of a given family of chemicals. It has been used for a long time as a refrigerant monitor and has a long maintenance life, but is only now being evaluated for use in vivariums. Whatever technology one chooses, these long-term upgrades work in tandem with software like Facility Prime by providing more real-time data on ammonia generation that can help the vivarium reduce operating costs.

Fuson sees few limits to what mobile BAS solutions can offer animal research. Already, there are significant productivity improvements to be had. “If you don’t have these monitoring systems, someone has to physically walk around and check on the animals,” he says. “If you have the information, you can be sure you’re not letting them get into a distressed condition, so you can go longer between cage changes.”

“The biggest challenge is figuring out the what-ifs,” says Fuson. “It takes time to sit with your team and figure out what information you want and where you want it. I want to challenge (lab technicians) to think, ‘If I had this information on my smartphone or iPad, how much more productive could I be?’ At least start the process by asking that question.”

By Liz Batchelder

This report is based on a presentation Fuson gave at Tradeline’s Animal Research Facilities 2013 conference.