Lacking space for its health science programs but faced with a limited budget, the University of Georgia is repurposing a former Navy Supply Corps School as a new Health Sciences campus, salvaging a property slated for closure and creating a more modern, collaborative learning environment. Throughout the renovation process, the challenges have been managing end-user expectations, balancing practicality with functionality—including reusing some materials—and dealing with diverse properties in this compatible but not perfectly matched space.

The University System of Georgia, which oversees 31 colleges and universities, has tasked constituents with finding new uses for existing facilities rather than undertaking new construction.

“They have made it clear that they no longer want the focus on new capital projects but rather effective reuse of the facilities that we have,” says Kathy Pharr, University of Georgia assistant vice president for finance and administration. “Our repurposing of a former Navy Supply Corps School as a health sciences campus has become a poster child for this effort.”

The project is driven by space needs, but also fulfills a goal to bring the College of Public Health and the Georgia Regents University (GRU)/University of Georgia (UGA) Medical Partnership together in a collaborative environment. The College of Public Health, founded less than 10 years ago, is one of the University’s fastest growing schools and most prolific generators of grant funding. GRU is the state’s only public medical college, and its innovative partnership with UGA has increased the number of medical students enrolled in each class. Thus, the pipeline of both doctors and other health care professionals is expanded. A statewide physician shortage brings urgency to the project.

“Georgia was on track to be dead last nationwide in the number of physicians to serve the state. With that issue percolating, we really needed to take steps to get more trained medical professionals into the community,” says Pharr.

Diverse Properties

The Navy Supply Corps School, placed on the federal government’s Base Realignment and Closure list in 2005, was decommissioned in late 2010. The property spans approximately 56 acres with about 460,000 sf of facilities. Its 20 major buildings run the gamut of architectural style, condition, age, and function. Seven historic buildings are on the National Register. The housing areas include traditional dormitories and suites, town homes, and single-family homes built in the mid 1950s to late 1960s. There is a clinic, officers’ club, hotel, commissary, childcare center, community center, and Navy exchange.

“It’s an eclectic mix. Many of the buildings will be used very differently from their original intention,” says Pharr.

The location, near two hospitals and less than two miles from the University’s main campus along the medical corridor in Athens, is ideal. In addition, there is also shared history—the University owned the property from the mid-1800s until 1950, before selling it to the Navy. In April 2012, the federal government transferred ownership of the Navy School to the Department of Education (DOE), which, after deliberation, transferred ownership to the University at no cost under a public benefit re-use agreement.

Four principles initially guided the project:

- Work only with existing buildings at the Navy Supply Corps School. No new capital projects are planned at this time.

- Establish a big footprint quickly/get the facilities into quick use. Under the terms of the agreement with the DOE, the University must demonstrate the facilities will be used as stated, with progress reports every two years.

- Phase projects based on academic priorities and budget restrictions. The University’s Board of Regents, which approves all campus construction projects over $1 million, is approving each phase of the work.

- Take a holistic approach to expanding the campus, providing both necessary infrastructure and student support, rather than creating a commuter campus. Plans call for a dining hall, residence hall, recreation center, and bus service from the main campus.

Scope of the Project

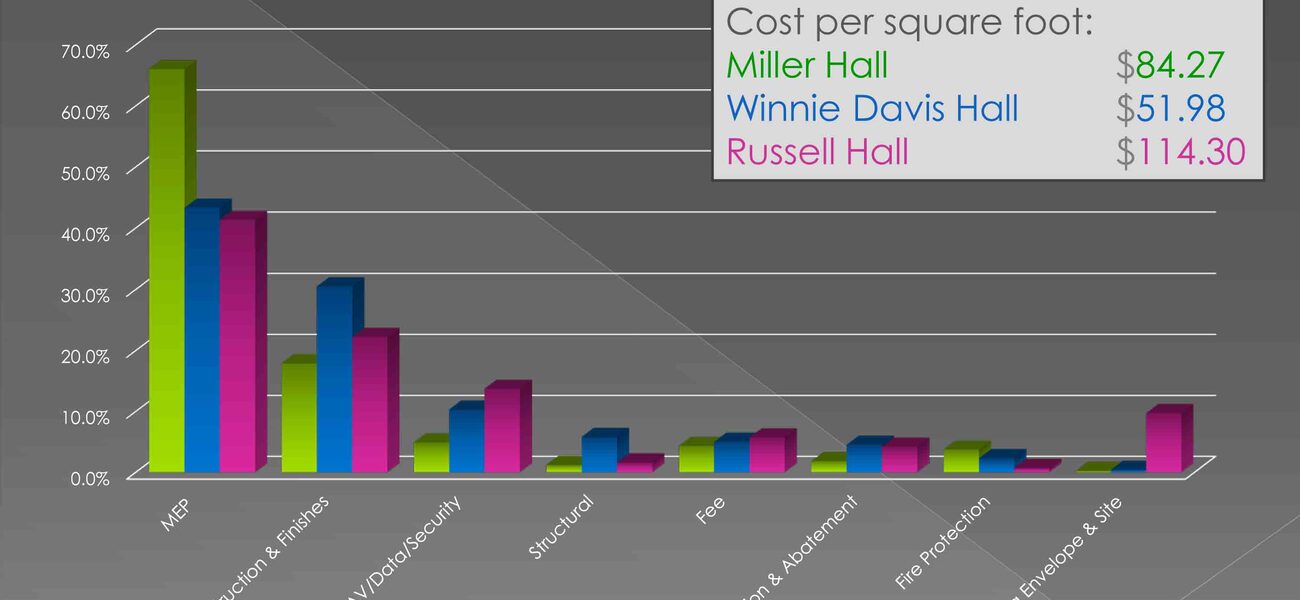

Already, the project offers additional breathing room. Phase I, approved February 2011 and completed in the fall 2012, provides space for about 800 faculty, staff, and students. By completion of all phases in late 2015, 1,600-1,800 faculty, staff, and students will be served. Phase I encompasses 102,150 sf, with a total project budget of $11.4 million. Of the three buildings renovated, about 60 percent of the budget was allocated to Russell Hall, a windowless building that required extensive interior work—including asbestos abatement, moving stairwells to improve interior circulation and meet fire codes, and improving egress from the second level—and exterior renovation to add windows.

Phase II, now underway, has a budget of $9.4 million and includes renovations to Rhodes Hall for the dean’s office of the College of Public Health, as well as a dining hall in the former officers’ club.

Phases III and IV, in design, have a total budget of $16.4 million. The scope of work includes renovations to Wright Hall, a former hotel, for office space for departments of the College of Public Health. The Navy’s Hudson Clinic, which has basic medical and dental exam rooms, will house Public Health’s Institute of Gerontology. Pound Hall, built in 1918, will be a dry lab.

Renovation of the rest of the facilities remains in planning. The University has so far raised about $500,000 in private funding for a $2 million renovation of the historic Carnegie Library building. Ultimately, a wet lab to accommodate the final department of the College of Public Health will need to be considered as a new capital project.

Managing Expectations

Throughout design, planning, and renovation, the University has worked hard to manage the expectations of stakeholders in the academic community and meet time and budget constraints.

“We have two distinct academic units, the College of Public Health and the Medical Partnership, each with its own big expectations,” says Pharr. “We had to be very open and build a level of trust with all of the people involved. Our decisions had to consider what was best for the development of this campus as a whole.”

While often extensive, much of the work may not be what end users expect to see after a major renovation. Many basic systems in these buildings are at the end of their lifespan (the newest academic facility was built in 1974) and must be upgraded.

“We needed to do systems work, ADA work, and meet fire codes and state codes for occupancy. We had a lot of fundamental work to do. We had to manage a budget and deliver functional space so, in the end, everything might not be bright, shiny and new, but it is good, quality space for the departments,” says Pharr.

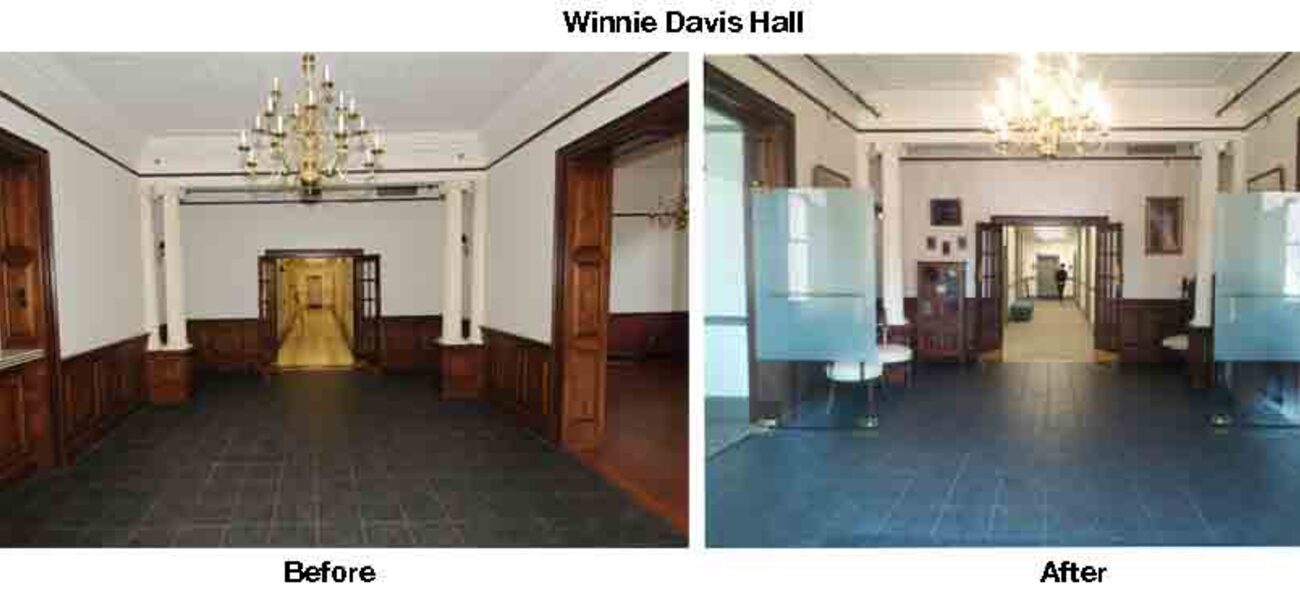

The challenge is to create no-frills, practical space without sacrificing program elements. Carpeting, furniture, and other fixtures are cleaned and re-used. “If it was something we could live with, we retained it. In most cases, the Navy did not leave us fully equipped buildings, but we are reusing a significant amount,” says Pharr. Russell Hall, for example, originally had cubicles in many of the classrooms. While some were in good shape, faculty members asked for flexible seating arrangements so students could work in teams. Instead of tossing out the cubicles, some are in the computer lab, while others are hoteling space for faculty.

Project Management

The University’s Facilities Management Division, responsible for repair and upkeep of these spaces after renovation, recommended using the services of Multivista, a photographic documentation and indexing company, to better understand existing conditions and streamline future maintenance. Multivista takes detailed interior and exterior photos to create a visual inventory of conditions within each building, making it easier to target the exact location of a problem before dismantling a structure. The service also provides an interactive site tied to construction documents to make test-fits easier.

“Our facilities division had a strong desire to document conditions we found during the renovation and all the work we are doing. With exact-build documentation now to target problem areas, hopefully it will be easier to successfully maintain these buildings in the future,” says project manager Krista Coleman-Silvers, the University’s design and construction manager for the new Health Sciences Campus.

The initial cost is relatively low compared to the overall budget—$15,000 in both Phase I and II—and Coleman-Silvers expects the service will save labor costs over the lifecycle of the project.

By Mary Beth Rohde

This article is based on a presentation Pharr and Coleman-Silvers gave at the Tradeline 2012 Academic Medical and Health Science Centers conference.

| Organization |

|---|

|

Multivista

|