Biogen Idec is exchanging the tired academic layout of a 20-year-old lab facility for an open and modular configuration that combines innovative “I” and “we” spaces to stimulate not only efficient space utilization, but also competitiveness and an alignment with the company’s scientific goals in a dynamic industry that requires the utmost flexibility in its researchers and their lab spaces.

Founded in 1978, Biogen Idec is the world’s oldest independent biotechnology company, and focuses primarily on neurodegenerative disease, autoimmune disorders, and hemophilia. The company operates in 29 countries, with direct commercial operations in 27, and three main research campuses in Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Denmark. They recently launched their fourth concurrent commercial product in the United States market.

Assembling the Team, Understanding the Challenge

Ed Dondero, director of real estate and planning for Biogen Idec, describes how they began their design process: “We selected and prequalified three firms and told them it would be a 150,000-sf renovation. That’s all the information they got.”

Upon arriving in the interview room, the firms’ designers were required to sit and say nothing for the 20 minutes or so it took for Biogen Idec’s team—including Dondero and Werner Meier, vice president of biologics drug discovery—to describe the vision and scope of their project. Afterwards, they were allowed to ask questions. “That way,” says Dondero, “they would understand this wasn’t just a patch-and-paint project. Going through that process, we selected a team [including the architectural firm Perkins+Will] that aligned itself with what we wanted to do.”

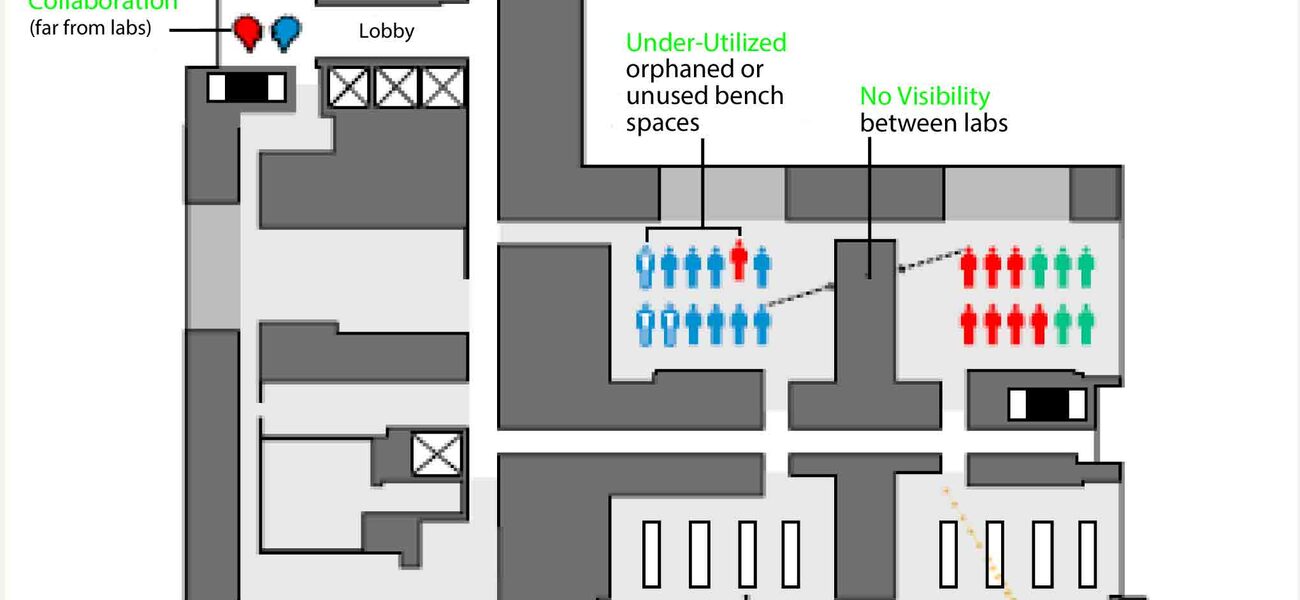

Biogen Idec’s 150,000-sf, six-story facility presented many challenges. It lacked collision zones where employees might spontaneously interact. The facility’s mechanical systems were below modern energy codes, and inferior chemical storage conditions were creating compliance problems. Additionally, Biogen Idec had recently merged with a smaller company but was having trouble integrating the new employees into their lab space.

The facility’s original layout of 12-person workspaces, while conceptually efficient, provided its own dilemma. “Functions don’t grow in units of 12,” says Meier. “They grow by twos, they grow by eights, they sometimes grow by thirties.”

Furthermore, Meier explains, “In order to have efficient equipment utilization, you want to have a critical mass of the same phenotypes in one place.”

But that number does not always work out evenly. And between over-12-person teams and under-twelve-person phenotype groupings, the Biogen Idec facility was left with rampant orphaning: great spaces that could not be fully utilized either because they were hard to perfectly fill or because they split teams, often across fixed structures that completely blocked visibility and communication.

Developing a Plan

Biogen Idec developed four tenets to guide them in visioning a new lab design:

- Full Utilization of lab floors, accommodating groups of varying sizes and needs such that no seats are orphaned.

- Adaptable Design, allowing changes in function, equipment, layout, and group sizes without major disruption or investment.

- Visibility, openness, and access to natural light within and between labs and offices.

- Increase in collaborative space, easily accommodating both scheduled and spontaneous sharing of data, ideas, and energy.

They then collected lab reviews, user interviews about the space, and discrete metrics about the laboratory, office, and equipment spaces. Data and tenets both were then filtered through three levels of functional groups, a working group of lab users, a governance group of senior facility and research managers, and a senior management group, which included the executive vice president of Biogen Idec.

“That process worked well, because it gave us all three levels of input, and everybody was informed,” says Meier. “At the end of the day, we had three options.”

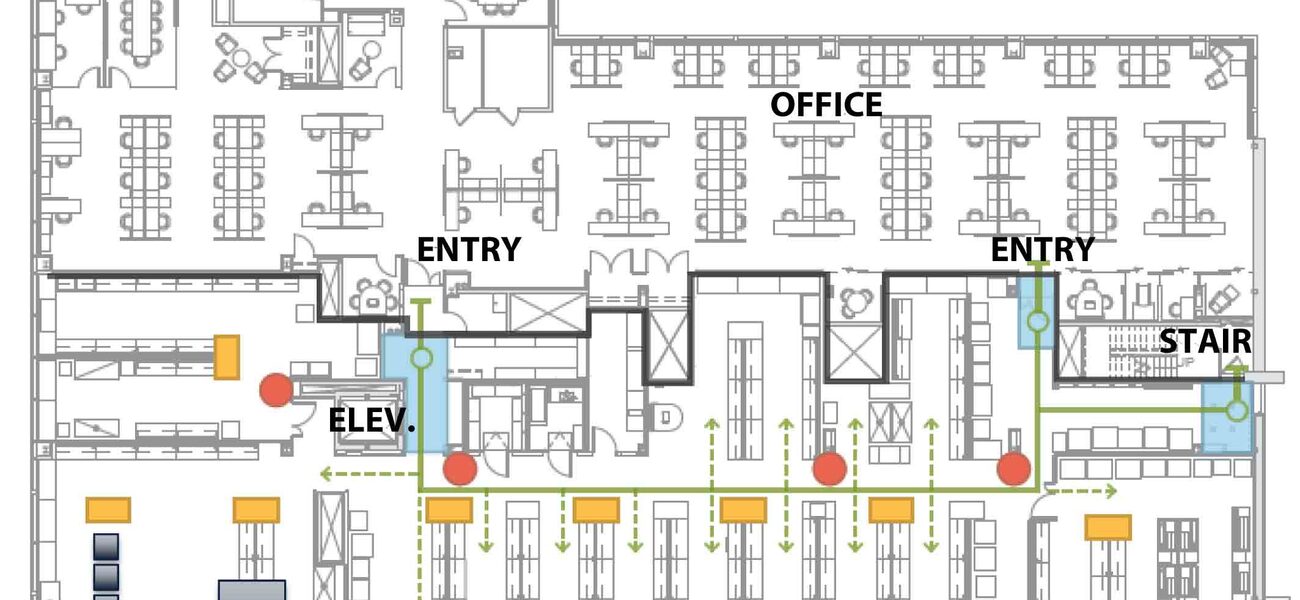

The first was a lab-centric model that featured full lab consolidation, an adaptable lab design, and an unobstructed openness across lab spaces. As its drawbacks, the design created three distinct office zones, a linear desk orientation, and limited all casual interaction in the lab area.

The second was an office-centric model, essentially the inverse of the first. While it offered visibility and openness, it traded lab integration for office integration. Likewise, it was hampered by three distinct lab zones, a stretched lab area, and casual interaction only in the office area.

The third was a hybrid model. The “upper” half of the space was devoted to an open office plan, while the “lower” half of the space was an open lab plan. Both labs and offices were consolidated, and casual interaction could happen anywhere on the floor. Its only slight disadvantage was a longer walk from desks to lab benches, but its many advantages, Meier believed, outweighed that one flaw.

The user, governance, and executive groups agreed. “It was interesting that this option turned out to be the favorite,” says Meier, “because it is very similar to what we have now. I think we were just used to it.”

The way facilities like Biogen Idec’s conduct research has changed, says Dondero. “Twenty years ago, the majority of collaboration and interaction happened at the lab bench. Today, because of technology and equipment, a lot of that collaboration now occurs in the office zone.”

In the hybrid model, the facility picked up more than 2,000 sf of office space while maintaining the same amount of bench and equipment space. The only sacrifice was lab support space, which Biogen Idec solved through increased flexibility.

Solving Problems with I Spaces and We Spaces

The first step to an adaptable lab space was to make everything moveable. In the new facility, only the emergency sink, eye wash stations, and a few load-bearing structural elements are fixed. Everything else can, and will, move as Biogen Idec’s needs require, shifting as quickly and easily as an overnight transition. “You can pretty much put anything you want anywhere you want,” says Meier.

This physical adaptability is supported by a conceptual structure: I and we spaces. “I spaces are spaces that people own,” explains Dondero. They have their nametag on them. They have pictures of their family and pets. The we spaces are where people go to work collaboratively.”

The we spaces represent a sea-change in Biogen Idec’s office policy. “For years we dictated how people work,” says Dondero, “but now we are allowing people to choose how they want to work, both in the office and in the labs."

Before, researchers were allocated set space on a lab bench and either a tech bay or an office, based on their title. Now, in the open concept facility, there are no closed offices. Everyone sits together, out in the open. Workstations measuring 6 by 8 and 6 by 4 are interspersed across the office zone, making up the researchers’ I spaces. Additional congregation spaces ranging from open lounges to traditional conferences rooms comprise the we spaces, where researchers go to concentrate, collaborate, connect, and learn.

The balance between I and we spaces is carefully maintained, with a minimum of 0.7 other seats per person. “For every hundred I spaces that we have, we have at least 70 seats in we spaces,” says Dondero. “Sometimes more.”

Additionally, in the office zones, researchers are given the option to set up in two-, four-, or six-person arrangements, depending on how they work best.

Working Towards a Dynamic Future

The project is ongoing, and researchers will be moving into the first completed floor in the next few months, with the facility’s other floors intended to be renovated over a 30-month period. Each floor’s renovation costs between $7 and $8 million, and consists of between 20,000 and 21,000 sf.

Included in that renovation process is a complete overhaul of the facility’s air handler and heat recovery systems. The existing water-cooled chillers will remain intact.

Meier’s hopes for the new facility design are high. Biogen Idec’s work is in a high-risk, high-reward industry. “The goal of this is to reduce that risk, to increase our chances of bringing important therapies from the bench to the bedside and ultimately onto the market. I think that we in research and all the way up to our senior leadership feel that this new lab concept is one of the key components that will allow us to do so in an efficient way by bringing everything together.”

By Braden T Curtis

This report is based by a presentation by Dondero and Meier at Tradeline’s 2013 International Conference on Research Facilities.