One might not typically associate North Dakota with the future of medical professional education and with fair reason: It is one of the least populated states in America to be home to a full medical school. But that perception may soon change, thanks to the University of North Dakota’s new School of Medicine and Health Sciences facility, opening this summer, which aims to move from aging, closed, and fixed learning spaces to open and adaptive, technology-integrated, interdisciplinary spaces.

Founded in 1905, the University of North Dakota’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences has offered a full four-year degree program since 1973, including not only traditional medical education, but also courses in physical and occupational therapy, public health, physician’s assistant programs, medical laboratory science, and athletic training. Students spend their first two years studying in Grand Forks, N.D., and finish out their third and fourth years in either Minot, Bismarck, or Fargo.

Attending these widespread campuses, to say nothing of managing them, was an onerous task; a round trip encircling the four is a 600-mile journey. Even within the main Grand Forks campus, the school has eight programs in six separate buildings.

As of 2007, prior to the oil boom that brought with it a sharp influx of migrant workers, North Dakota faced an imminent shortage of 300 physicians. To combat this, administrators from the School of Medicine drafted a Healthcare Worker Initiative (HWI) that called for a 30 percent increase in medical school enrollment and a new $25 million health sciences facility to attract and support those students.

Work on this Initiative continued until late in 2010 when, says Randy Eken, associate dean for administration and finance at the School of Medicine and one of the HWI planners, the realities of the upcoming 2011 North Dakota Legislature necessitated a change in strategy. “We knew in the next session that we were not going to get approval for a new building,” says Eken. “We weren’t prepared. We didn’t have the data.”

New Data Feeds a New Proposal

Rather than simply calling for a new $25 million facility, the University successfully lobbied the Legislature to appropriate $100,000 to complete a space utilization study. The University hired local firm JLG Architects, in collaboration with Steinberg Architect’s medical education planners, to carry out the space utilization study with three primary areas of concern. First, could the University’s existing (old) facilities support modern health education? Second, were the existing spaces being efficiently utilized? Third, were the classrooms and laboratories sufficiently large enough to support the increased class sizes that the University sought?

In short, the answer was no. While the University’s space utilization was on par with its peers, “the room functionality of the classrooms was very poor when looking at how they wanted to teach versus what they were able to teach,” says Andrea Stalker, a senior associate with Steinberg Architects. “There was a misalignment between a very progressive curriculum and a facility that did not support that, and a misalignment between the sizes of spaces that they had and their actual class sizes.”

The design team initially drafted two proposals: The University either could build a $38.5 million small addition to the existing facility, just enough to expand the space to meet the needs of their desired enrollment, or spend $68.3 million on a large renovation and addition that would not only accommodate new students, but also draw the disparate programs on the Grand Forks campus together in a single united facility.

“Most of the leadership thought that the large renovation was the right answer,” says Bob Lavey, a partner at Steinberg Architects. “Then Randy had a crazy idea.”

Eken—with the strong support of Dr. Joshua Wynne, dean and vice president for Health Affairs—proposed the construction of a new $124 million facility. “The first two proposals did not include research at all,” says Eken, and therefore negated any opportunity that modern medical research facilities might provide. “We presented the case that the new building had an income opportunity over 40 years of about $36.9 million.”

Further, by freeing the University from its aging buildings, the new facility would recoup $18 million in operations and maintenance savings. “The bottom line was that there was a difference of less than $1 million in the total cost over 40 years for the brand new building,” says Eken.

So, not such a crazy idea. In May 2013 the North Dakota Legislature agreed, and approved this third proposal.

Open Spaces Feed Open Minds

This new 318,000-gsf facility is comprised of roughly one-third education space, one-third research space, and one-third office space. Its design incorporates three key elements: collaborative high-tech classrooms, interprofessional learning communities, and knowledge and research resource management.

Patient-centered learning spaces (PCLs), which house both study and social space for seven or eight students each, were already central to North Dakota’s medical curriculum, but were among the facility elements to be rethought and updated. By separating social spaces from learning spaces, architects were able to create a greater number of more flexible spaces.

The new PCLs, for example, can comfortably hold up to 14 people and are program-agnostic, providing a flexible learning space for not just medical students, but any of the variety of health sciences students who occupy the building. And since they no longer need to accommodate social spaces, there are more of them within a smaller footprint.

But that is not to say that social spaces have been abandoned. Rather, they have been reconsidered as a part of a new focus on interdisciplinary education. “We knew that students were siloed, if you will, between all the different programs of medicine, health sciences, and medical lab sciences,” says Lavey. “The University’s goal was to connect these students, not just in classes but socially.”

“Of the 800 or so students who will be in the program,” he says, “we figured that groups of about 100 each are somewhat of an intimate group; 200 is too many and 50 is too small. We also looked at pairing two communities together. So the groups of 100 share a social lounge space in the middle which has the bar, the oven, and the refrigerator where you put your food.”

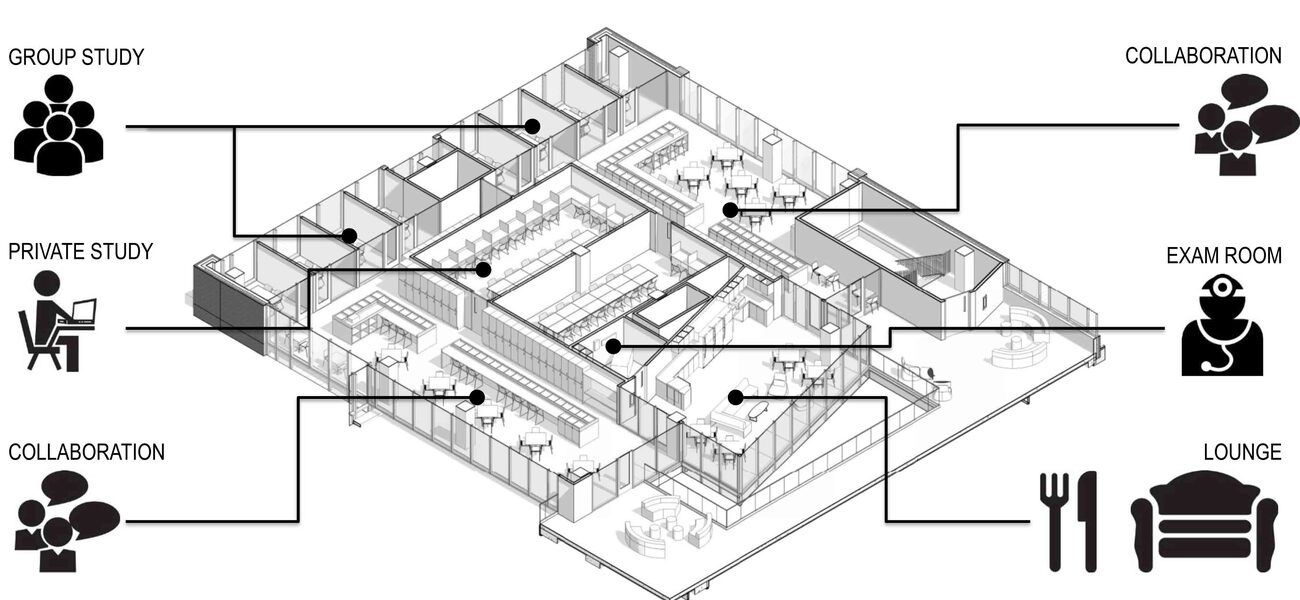

The eight student community spaces are each paired off in this manner, and then each pair is paired again with the floor above it, creating two 400-student greater communities, one on the north end and one on the south end of the building. Not underestimating the importance of private space, each community space has student lockers and quiet study carrels, in addition to shared practice exam rooms and schedulable group collaboration spaces.

The facility is, at its heart, a student-driven space, constructed with their needs in mind. When the architects surveyed medical and health science students on the importance of cadaver study, the response was “overwhelming,” says Stalker. “It was critically important to them, so much so that they would not attend a school of medicine that did not have a cadaver-based gross anatomy lab.” This led Steinberg and ultimately, the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, to include a cadaver lab in the new building.

One thing you won’t find in the new building are any book stacks. “Today’s medical education and health science students are not going to a library to find a book,” says Stalker. “They are going to the library to find someone who can help them find the information they are looking for.”

The new building does not have a traditionally delineated library space; instead, librarians are dispersed throughout the building at workstations in offices and near student collaboration spaces, providing them more immediate access to the students and faculty they serve.

All considered, the new building will enable a 15 to 30 percent increase in occupancy with a 22 percent reduction in total square feet over the University’s previous facilities. This includes a 20 percent increase in available space for teaching, a 24 percent increase for research, a 112 percent increase for clinical study, and a 29 percent increase for offices and carrel space. Only faculty and administrative spaces will see a reduction in the new facility, and then only by 13 percent.

Managing the Change

“There are two things that people don’t like,” says Eken. “One is the way things are and the other is change.”

Adapting to the new space will require several changes for students, faculty, and administrators alike. At present, all of the University’s research labs are closed labs: “The faculty have their own office and their own lab in 600 sf, and that is it,” says Eken. Having open labs in different locations will be, as he puts it, “a huge thing.”

Another change will come in the form of active learning classrooms. The new building has only a single lecture hall, with the remaining 24 classrooms using the active learning model. Not only that, but also unlike the owned classrooms of the old facilities, every one of these is a shared space.

But the University is not taking a passive approach to the transition. Eken says that while you can never know whether people will be happy or unhappy about a new building, “you might as well assume that not everyone will be happy right away.”

Eken has assembled a “transition champion team” of 50 faculty, students, and staff from departments across the School of Medicine and Health Sciences. This group of ambassadors will work with the various learning communities, which are themselves student-centered and student-run, to make the move-in as smooth as possible in the lead up to the first full semester of classes taught in the new facility in August, and the building’s grand opening in October.

They call this process “Coming Together,” and it’s not hard to see why.

By Braden T Curtis