The 12-story McGlothlin Medical Education Center at Virginia Commonwealth University, completed in 2013, facilitates a new model of collaborative, team-based learning. The C3 curriculum—centered on the needs of the learner, clinically driven, and using competencies as outcomes—reflects a two-year process of reinventing the first and second years of medical school (M1-M2) involving the dean, faculty, executive-level curriculum staff, and students. They looked for answers to two questions, explains Keith Hayes, senior director of Strategic Design & Project Management in the School of Medicine: How are we going to address the issue of students retaining information if they are in the lecture-based environment; and, is there an opportunity to engage and include collaboration, integration, and technology, to make that process better for our students?

The 200,000-sf instructional building houses two floors dedicated to simulation and clinical skills learning; two floors of dry lab research to support the Massey Cancer Center; a 250-seat tiered auditorium; an administrative floor, with the dean’s suite; an entry floor, with a student lobby and the admissions office; a bridge to VCU’s hospital; and four floors of innovatively designed first- and second-year (M1 and M2) classrooms. The facility was designed by Ballinger in association with Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, and built with a construction budget of $100 million and a total project budget of $156.8 million.

An Innovative Curriculum

A commitment to active, collaborative learning drives the C3 curriculum. Large group lectures have limited effectiveness in helping students retain information, transform knowledge to novel situations, develop problem-solving skills, or become motivated for additional learning. Collaborative learning replaces the traditional lecture-based model with groups of students working together to solve a problem, complete a task, or produce a product. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME, the accreditation board for medical schools) gave medical schools around the country a mandate to incorporate active learning in their curriculum. At VCU’s medical school, faculty engage students in learning that is case-based, team-based, and problem-based; involves process-oriented guided inquiry; and uses simulation from the first day of medical school.

In the classical model of medical education, the first round of classes covers the basic medical sciences, followed by classes organized by anatomical systems. The classical model also separates the basic sciences from students’ clinical experience. Rather than a few changes to the School of Medicine’s existing classical approach, the C3 curriculum represents a complete shift in pedagogy. Instead of organizing coursework by conventional basic sciences and anatomical groupings, the C3 curriculum is organized around thematic subgroups, such as “Molecular Basis of Health and Disease” and “Glands and Guts.” By teaching basic and clinical science in tandem, the School of Medicine was able to condense the M1-M2 years from four to three semesters, giving students an additional semester of lab and clinical experience and more time to prepare for their medical board exams.

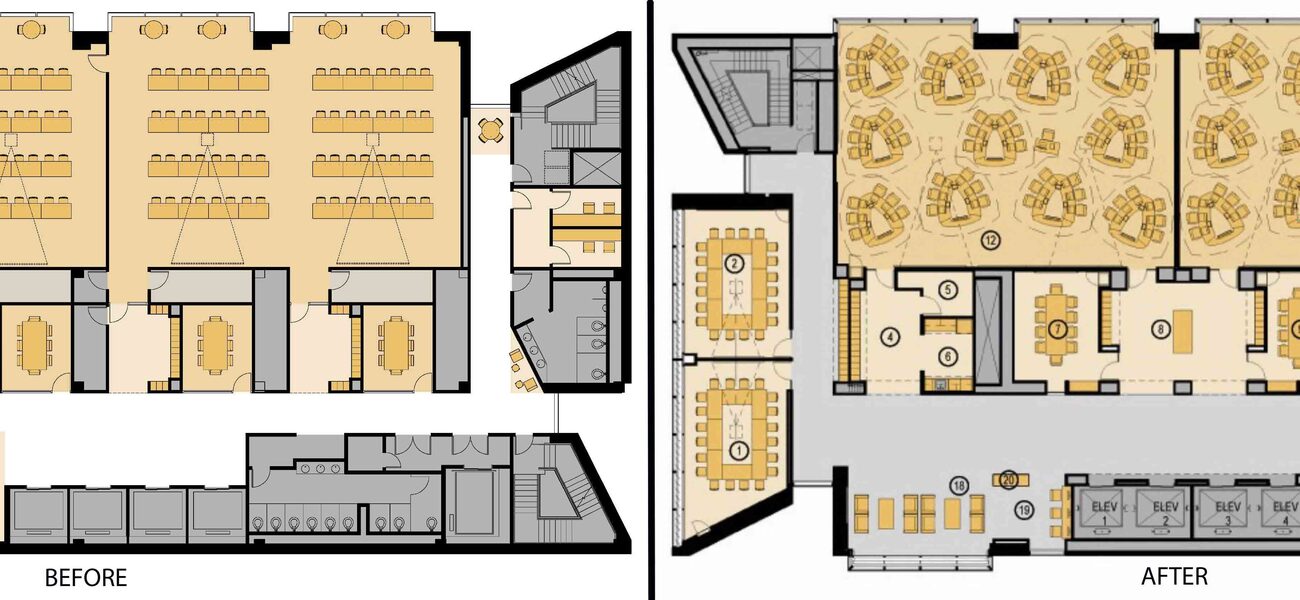

The C3 curriculum changed not only the structure of the curriculum, but the format of classes. Before making the transition to the C3 curriculum, classes took the form of two- to three-hour lectures. Under the C3 curriculum, a great deal of class time is spent in collaborative learning. Creating classrooms that support both lecture and collaborative learning was a main challenge in designing the McGlothlin Center. “There is always going to be a lecture component with medicine,” says Ed Gillikin, principal at KOP Architects, and project executive during the design and construction of the McGlothlin Center. “We wanted an active learning environment that could support lecture yet maintain the group dynamic.”

The McGlothlin Center design team looked at MIT’s TEAL Center as an example of a collaborative learning space. Before opening the TEAL Center, MIT’s introductory physics class, taught in a traditional lecture-based format, had only 40 percent average attendance, and 13 percent of students failed the course. Attendance in the TEAL Center has more than doubled, to 95 percent, while the failure rate has fallen to 5 percent. “A classroom with conventional learning modalities equals a boring class,” says Gillikin.

Structure and Technology to Support Collaborative Learning

“Historically, space has driven pedagogy,” explains Gillikin. “The rectangular classroom is geared for passive learning.” The classrooms in the McGlothlin Center are designed to facilitate active learning. Instead of rows of tables, the C3 classrooms contain 11 tables that are shaped like shields and seat six students.

The C3 classrooms occupy the same space as the original lecture hall design, while seating two additional students, but cost substantially more to build. The original design called for $75,000 to be spent furnishing the classrooms, with negligible AV technology expenses. Furnishings and AV technology for the C3 classrooms cost $1.4 million. Per seat, costs increased from $146 to $2,562.

The four floors of classrooms are divided into two sets of adjoining floors, each with two classrooms. During lecture, the instructor simulcasts to all four rooms. During the collaborative portion of the class, the instructor and a graduate assistant can float around to the different rooms to assist students with their work.

Each table is equipped with a pair of monitors, one for the professor to share material during lectures and the other for students to share their laptop displays. Students can also view the lectures on larger screens at the front of the classroom. When the professor finishes lecturing, the monitor showing lecture material is released to the students’ control. Lectures are recorded and archived for later use by students.

The size and placement of the monitors posed a challenge for the design team. After experimenting with various sizes, the team settled on 40-inch monitors on Steelcase® mounts. The monitors are positioned at a 13-degree angle to preserve students’ line of sight.

After lectures, the large screens at the front of the room roll up to reveal whiteboard paint, on which students post their responses to in-class exercises. The walls are divided into numbered sections corresponding to numbers on the tables. A camera in each room can focus on the different numbered sections, which the instructor can view with a tablet device, and students can communicate with the instructor using a microphone.

Typically in higher education, IT and AV are separate departments, but the technology that facilitates collaborative learning in the McGlothlin Center necessitates a deeper cooperation between the University AV and IT teams. The two departments also had worked together extensively during a previous construction project for the School of Pharmacy.

The McGlothlin Center had an original AV budget of $4.5 million: $3 million for classrooms, $1 million for the auditorium, and $500,000 for miscellaneous expenses. The final AV budget ran $7.5 million, mostly from $2 million spent on simulation and clinical skills learning. Classroom expenses rose to $3.7 million, and the miscellaneous category to $800,000. The cost of the auditorium did not change.

The School of Medicine built the McGlothlin Center with an eye toward increasing class size. Before moving in, the school had a class size of 185. This year, 218 students enrolled, with a target of 250 students. With 264 seats, each pair of M1-M2 floors can easily accommodate these larger classes.

Getting faculty to buy into the collaborative model of the C3 curriculum was key to the project’s success. Hayes says that creating a mock classroom a year before construction “helped dramatically.” Faculty members volunteered to teach classes in the mock classroom using the new collaborative learning model, and their positive experience was crucial to earning faculty support.

The faculty’s adaptation to the McGlothlin Center and the C3 curriculum has led to an improved experience for students. “The faculty started using the new curriculum in July 2012, with the class of 2017, and feedback from students has been positive. “Once they are in their M3 years, students are able to really synthesize and bring information in the real-world clinical environment much faster,” says Hayes. In spring 2017, a comprehensive, four-year assessment of M1-M2 metrics will be available to compare student performance under the former pedagogy.

By Mark Engleson