The master plan for Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland, Ore., offers valuable lessons in how public-private partnership and well-tended relationships with neighboring developments can overcome significant growth constraints. The university found ways to eke out space and funding for new buildings and programs where little seemed to be available.

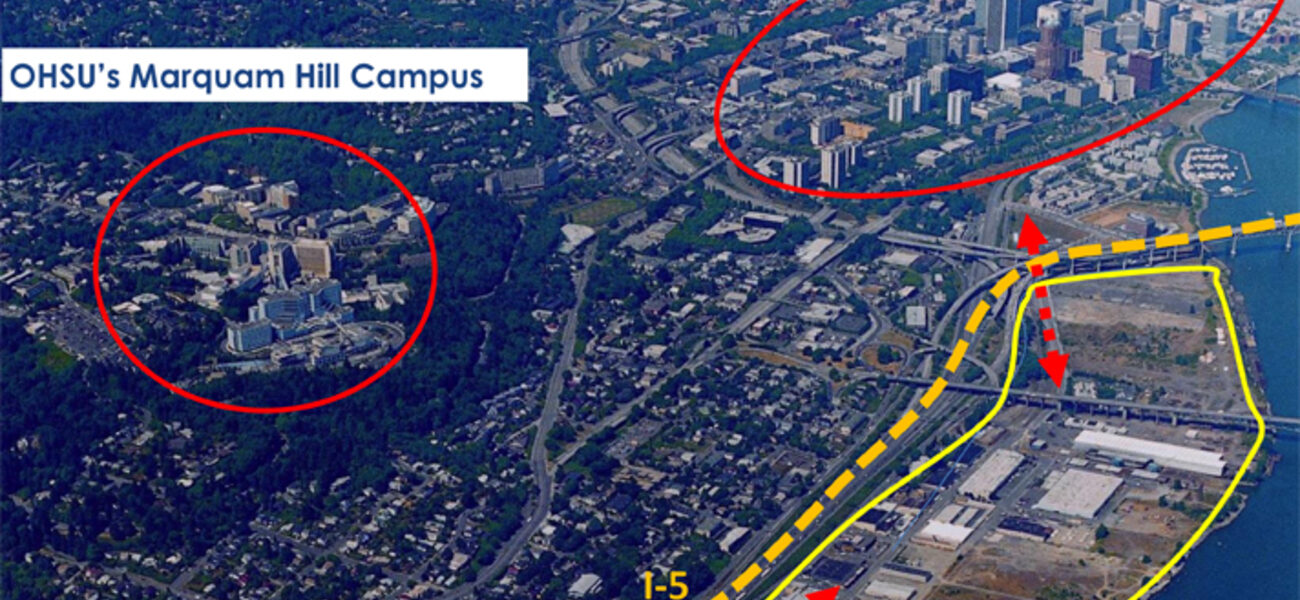

OHSU is the only academic medical center in the state of Oregon and, with 14,000 staff and growing, the City of Portland’s largest employer. The school’s 4,000 medical, dentistry, nursing, and pharmacy students are located primarily on the 5-million-sf main campus on Marquam Hill, which is also the site of a 600-bed VA hospital and a Shriners Hospital for Children, along with significant research facilities. Over time, the university has purchased or received through donations additional acreage, translating to roughly 2 million sf, on the Willamette River’s South Waterfront.

“We have been operating on Marquam Hill for about 100 years, and every inch of developable land has been taken up,” says Brian Newman, OHSU’s director of campus planning, development, and real estate. “We have had to resort to expensive solutions, like building our children’s hospital to span a canyon.”

Although OHSU owns 300 acres of flat, easily developable land 20 miles west of Portland in Hillsboro, Portland provided incentives for the university to grow in place, including construction of the Portland Aerial Tram to shuttle OHSU and public passengers the 600 vertical feet between the South Waterfront and the Marquam Hill neighborhood. Expanding in the South Waterfront would necessarily involve cooperation with the city and adjacent private development.

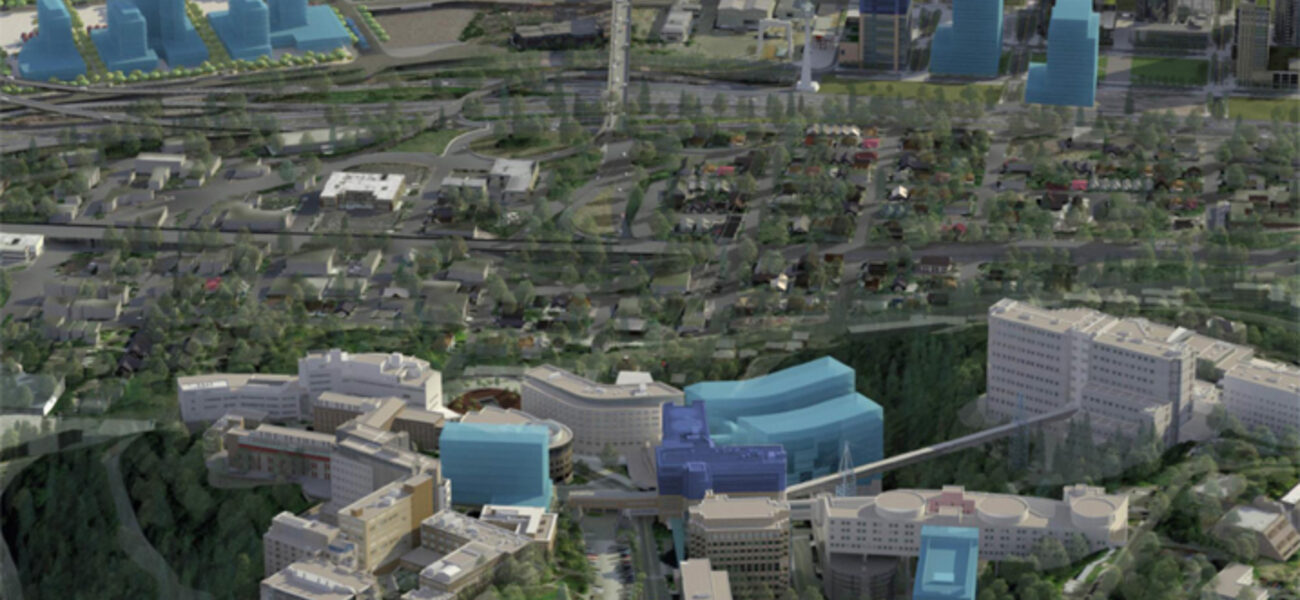

The university hired a master planning team including ZGF Architects LLP, a Portland-based multi-national firm, and a smaller local firm, PKA, to examine two parts of the South Waterfront area available for development: the Schnitzer campus and the Central district.

“ZGF was very fortunate to work with the Zidell family, which owns the property between the Schnitzer campus and OHSU’s existing Center for Health and Healing,” says Stefanie Becker, an associate partner at ZGF. “Fortunately, there is a high degree of symbiosis in terms of the best uses of both Zidell Yards and OHSU property. It’s beneficial for Zidell to develop complementary amenities and land uses such as housing, shopping, and offices for firms that do business with OHSU.”

Guidelines for Vision and Implementation

The master plan was derived from five guiding principles: It had to be achievable, integrated, flexible, balanced, and accessible. “We needed to integrate the campuses with the programs on the hilltop; keep everything accessible for staff, students, and patients commuting between Marquam Hill and the waterfront; and leave that degree of free play, in case a major donation happened to make new development or renovations possible,” says Becker.

Eight themes also shaped the master plan:

- Preserve remaining development capacity on Marquam Hill. “We have a huge amount of investment there,” says Newman, “but we had to look at what could be torn down to make way for future development.”

- Preserving 12 acres near the South Waterfront tram station for outpatient expansion and to centralize support services.

- Over the next 25 years, migrate all academic schools and programs off Marquam Hill to the Schnitzer campus.

- Consolidate research in two locations. This met with some resistance from OHSU’s staff. “(Research) wanted to be everywhere, which was a challenge because the facilities are disconnected. We had to go through a thoughtful process about consolidating, because wet labs, microscopies, animal support—all of these basic elements—are expensive to build and maintain.” The decision was made to keep core research on Marquam Hill and to restrict future research growth to the Schnitzer campus.

- Home in on space constraints on Marquam Hill. Facility expansion was to be directly linked to building demolition and backfill. The existing School of Dentistry on Marquam Hill is to be demolished, with that school moving into the new Collaborative Life Sciences building on the Schnitzer campus, completed this month. “The university wasn’t always great about demolishing older buildings,” says Becker. “It’s understandable, because fully depreciated property is cheap office space. So it was important, given the site constraints, that the master plan enforce some discipline about tearing things down.” Five other buildings have been identified for demolition as of March 2014.

- Develop complementary relationships between buildings and open space on Marquam Hill.

- Further enhance accessibility to high-capacity transit.

- Achieve high levels of sustainability on all new development. “LEED Gold is the baseline for all of our new buildings, and we aspire to achieve LEED Platinum, as we have done with our two most recent buildings,” says Newman.

The master planning process itself was fairly straightforward. The OHSU team established three steering committees, and conducted interviews with a broad range of other stakeholders.

Growth constraints were the biggest issue, which both Becker and Newman say is typical when an institution is expanding as fast as OHSU.

“Other urban areas have solved their growth challenges by building at completely new sites,” says Newman. “At UCSF in San Francisco, for example, they have the main Parnassus campus, but the corollary campus is across town at Mission Bay.” At times, the master planning team found such examples helpful in conversations with OHSU staff who are used to being able to transition quickly between teaching, clinical, and research appointments by simply walking from one building to another. “Although travel distances between buildings increases with the Schnitzer campus, the tram is a good compromise for the users. It’s a three-minute commute with the most spectacular views of the city,” says Becker.

Three Previous Plans, One “Three-Legged Stool”

Perhaps most critically, the master plan was integrated with previous private and city-driven plans, and supported by city infrastructure. “We were looking to grow within the context of three other major plans: the Marquam Hill plan, the South Waterfront plan, and the Schnitzer campus master plan,” says Becker. OHSU was deeply involved in the Marquam Hill plan, which set out regulations for growth on the hilltop.

“We don’t push the limits of the Marquam Hill plan,” says Newman. “We work within them.” This degree of respect has been key to “good neighbor” relationships with the city, the surrounding residential neighborhoods, and the Zidell family.

The South Waterfront plan was a public-private partnership between OHSU, private developers, and the city. Alongside the OHSU Central district area, residential towers with street-level retail were developed while plans for multiple infrastructure improvements were underway. “We refer to it as the three-legged stool,” says Newman. “We needed the city to go into debt to pay for all of the infrastructure, and we needed the private developers to build the housing and retail, from which property taxes go to paying off the city’s debt. We needed OHSU to anchor the district and generate demand for housing and other amenities.” Without any one “leg” of the stool, the plan could not have been implemented.

Infrastructure improvements, particularly to public transit, were also interdependent with the university and housing. In addition to the tram, a new bridge for light rail, streetcars, buses, bikes, and pedestrians is under construction—the first new Willamette River crossing in 40 years. “We wanted that bridge to land at the front door of our first building,” says Newman. “We had already planned to raise the elevation by 20 feet in some areas to get above the floodplain, so now we have direct connectivity with the new bridge.”

Finally, the Schnitzer campus master plan, developed by ZGF with Perkins+Will, underwrites OHSU’s expansion in a major way. “That acreage allowed us to take education and some of the research off the hilltop,” says Becker.

It’s Not Just About OHSU

Being a “good neighbor” was a practical concern for the OHSU master plan process. “I can’t emphasize enough that you can’t just limit your plan to your institution,” says Becker. “You have to look at the ways you can leverage private and public partnerships and resources to make it happen.”

“It’s not just about OHSU,” says Newman. “It is about the Zidell family and their property, and about the city of Portland and other private developers. Even though the master plan is focused on OHSU, a lot of it is really about how we integrated with our neighbors and with the larger context of Portland. There has been reciprocity with our elected officials, as well. They have provided a lot of resources, and in return OHSU has been vocal in support of the investment that they’ve made—building alliances, getting people to hearings, and being advocates for the community benefits.

“All of the implementation and the leveraging we had to do to be able to pay for it—we often refer to it as the silver buckshot as opposed to the silver bullet. It was a huge undertaking, and we will be implementing it for years to come, but it’s been well worth the effort.”

By Liz Batchelder

This report is based on a presentation Becker and Newman gave at Tradeline’s 2013 Academic Medical and Health Science Centers conference.