Carefully coordinated stakeholder engagement is critical in the design and redevelopment of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) facilities. Effective buildings for the teaching of STEM disciplines are designed by understanding the desired pedagogy, and by enlisting faculty throughout the process to help align the resulting facilities with a school’s culture and mission, according to Christopher Chivetta of Hastings+Chivetta Architects and Stephanie Fabritius, vice president for academic affairs and dean of Centre College in Danville, Ky.

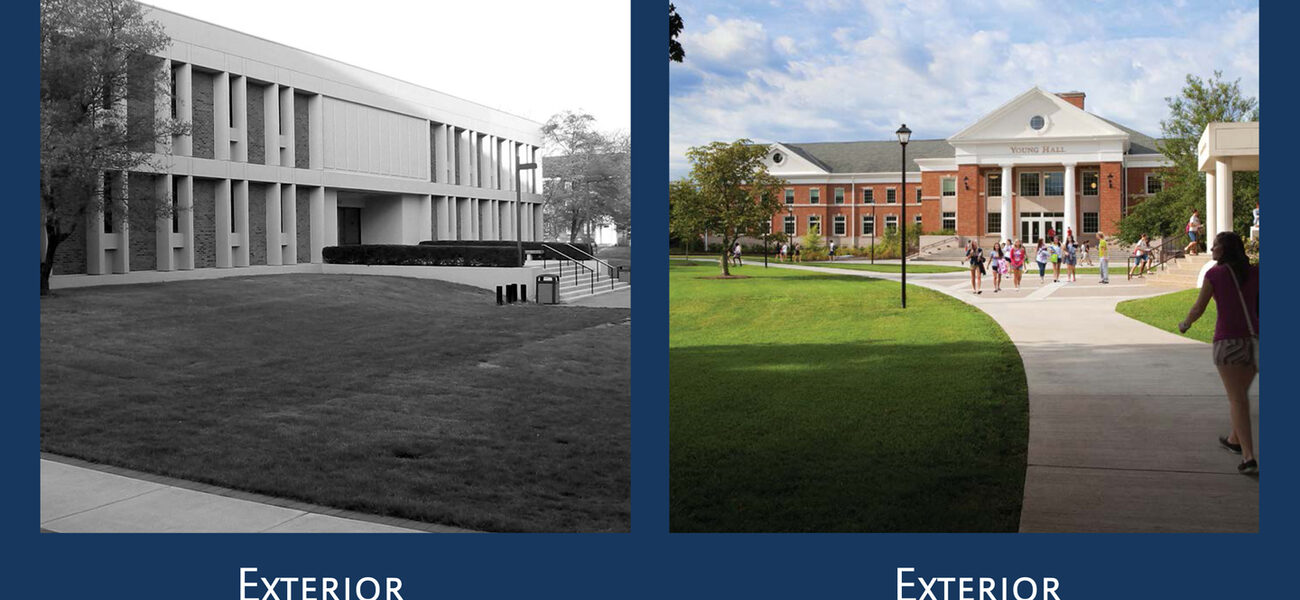

In the case of Centre College, a residential liberal arts school with about 1,370 students, the testing ground was Young Hall, a dated and uninviting 1960s-era life sciences building. Badly in need of renovation, the building did not encourage students or professors to linger or collaborate, and was rarely the first choice of the admissions staff when giving campus tours. “The space had tended to shape the teaching rather than the other way around,” says Fabritius, “so a primary goal of the renovation was to add new teaching and collaborative spaces, and to do some brightening and rearrangement of the old ones.” The $20.3 million project added approximately 43,000 sf of new space to Young Hall’s existing 58,200 sf, and included 11,500 sf of renovations.

The 43,000-sf, LEED-Gold-certified addition includes offices, collaborative research and teaching laboratories, classrooms, and space for students to engage in 24/7 study. Existing classrooms had been cramped and arranged traditionally, with rows of desks facing front. The new classrooms have a variety of arrangements depending on instruction and learning goals: conference-style tables, small tables that seat four, traditional desks, and U-shaped tables to encourage discussion. Some chemical laboratories were updated with transparent fume hoods to create better lines of sight in addition to improved ventilation, and the biology lab’s movable benches promote flexible use of the space.

The wide hallways are brightly lit, and windows into teaching laboratories allow visiting students to observe while introducing more natural light. New collaborative research spaces accommodate faculty-student teams, with small to large groups. Some faculty office spaces abut the collaborative student spaces to encourage even more interaction, an idea that was at first met with skepticism due to noise concerns but has since been embraced to the degree that further expansions of that type are planned.

Additionally, the new facilities are not “owned” by sciences and math but are open to the whole college. Teachers and students from various disciplines have been invited to try the new classrooms and work spaces, and the variety of configurations has been both a boon and a challenge. “The registrar has to keep track of which room has which features, because people definitely have preferences,” says Fabritius.

The success of Young Hall’s remodel is a direct result of an intensive stakeholder engagement process, beginning with the initial visioning work and continuing through design and construction. “With a building that is going to contribute to STEM education, we need to consider flexibility, student enrollment fluctuations, and relationships among disciplines very carefully so the environment can evolve along with changing needs,” says Chivetta. They organized committees comprised of stakeholders, then created feedback mechanisms within these committees to assist in managing expectations and satisfying program needs.

The four committees developed by the project team were executive, design, administrative, and stakeholders, with the fourth including campus administration and special events and maintenance staff, among others not limited to building users. Prominent among the executive group were the president, vice president for finance, and Fabritius, who is the dean and vice president for academic affairs. The design committee included representatives from faculty and students across all sciences and math disciplines, two trustees, the vice president for development, vice president for finance, and the director of the physical plant. The design committee also included Fabritius and Dr. Keith Dunn, division chair for the sciences and math at the time (now at Millsaps College) who served the crucial role of “project shepherd.” Fabritius, Dunn, and the vice president for business comprised the administrative committee.

The project shepherd role was popularized by Jeanne Narum through her work with Project Kaleidoscope, a national organization promoting leadership in the sciences. The project shepherd minimally serves as a liaison between administration and faculty, relaying feedback and helping both to achieve consensus and to set expectations. Excellent listening skills are essential for the person fulfilling this role, who may also lead the design committee. His or her commitment to the project extends from visioning through design, construction, and completion, and often demands troubleshooting on a variety of issues, whether interpersonal, technical, or budgetary. Fabritius worked in tandem with Dunn early on, in both design and administrative committees, to assert the accountability benefits of a project shepherd.

With the committees in place and the project shepherd appointed, the visioning phase continued to engage stakeholders by encouraging them to “dream big,” but with the clear knowledge that every desired outcome might not be spatially or financially feasible. Chivetta encourages tours of successful and landmark facilities at other campuses that can provide vision for technology, physical space, and collaborative research objectives. “A lot of times faculty have been in the same buildings for 20 years, and they may need to get out of their typical environment in order to access some bigger, different ideas,” he says. “Sometimes the biggest discussion is whiteboards versus chalkboards, because some educators are so entrenched in the way they’ve been doing things that it’s hard for them to embrace alternatives. One of the most important parts of the visioning process is to educate a discipline about new technology and techniques in the classroom or lab.”

The design committee and project shepherd must strike the right balance between creative thinking and realistic expectations. “Some faculty may think, ‘All I need is more space, or different storage solutions, or upgraded equipment,’” says Chivetta. “Once we’ve really pushed the envelope by showing them what’s possible, we need to let them know that all of these opportunities will likely not be realized in any one renovation or new construction undertaking. But regardless, we want a big, complete list. We want them thinking about how programs might collaborate, how space might be shared or individualized. I tell them, ‘You may need to walk through a few mansions to figure out what is important to you in your own house.’”

As the vision evolved, it was shared on the college’s intranet and initially made available only to faculty in math and sciences, then opened to all faculty after the architects were selected. All of the stakeholders were anxious to begin the process of working with architects, for which Chivetta recommends a “Five Cs” screening process. “The Five Cs of consultant team selection are control, competence, communication, creativity, and chemistry. The consultant team needs control to organize the project to specifications within budget and on schedule. Each member of the team also needs the professional competence to provide the highest quality design work. Communication needs to be free-flowing and comfortable. You need creativity to find design solutions that are unique to the project’s requirements, and chemistry within both the consultant team and the selection committee to make sure there is mutual trust and respect.”

Conflicts were fairly minor in the case of the Young Hall renovation, although Chivetta stresses that more parochially structured school administrations tend to have more disputes between departments over “who is getting what.” “On any project of this type, we head off conflict by being transparent. Institutions don’t have infinite resources, and frankly, every program doesn’t require the same amount of space. Ultimately, it comes down to what you can afford and what is going to advance the institutional mission,” says Chivetta.

With Young Hall, “hot-button” issues included how much space to allow for chemical storage or whether to create space for psychology students’ data collection in the vivaria, and the degree to which faculty would be interspersed rather than in phalanxes by discipline; they preferred the latter. Resolution of these conflicts was often led by the project shepherd. “At the most basic level, it involved long conversations to help those with differing opinions understand our need for compromise,” says Fabritius. “If we couldn’t reach consensus, the executive committee would weigh in.” However, there was general understanding that finances were a big driver.

In retrospect, one of Fabritius’s few regrets about the Young Hall renovation was that it didn’t include more collaborative spaces, especially near faculty offices, because of resistance from stakeholders. “Some people said, ‘We’ll never use them,’ or, ‘They’ll be too noisy,’” recalls Fabritius. “Now, after seeing them in use, people are asking for more of those spaces.”

Crucially, a good project shepherd develops a high level of trust with faculty, the project team, and the highest echelons of decision-making. “In those few conversations that looked like they could turn into complaining sessions, our willingness to talk things through ultimately kept things under control,” says Fabritius. “The chair and the project shepherd had to be prepared for the meetings and to anticipate those that might have a an objection or alternate view. But from the beginning, we talked pretty openly about having the space fit our vision and meet real, demonstrable needs.”

The result in Young Hall has been a dramatically improved learning environment as well as a new benchmark for collaboration on campus.

By Liz Batchelder

This report is based on a presentation Chivetta and Fabritius gave at Tradeline’s College and University Science Facilities 2013 conference.